Three Rivers

Hudson~Mohawk~Schoharie

History From America's Most Famous Valleys

The

Mohawk Valley

Its

Legends and its History

by

Max Reid

New York and London G. P. Putman's Sons

The Knickerbocker Press, 1901

with illustrations from photographs by J. Arthur Maney

|

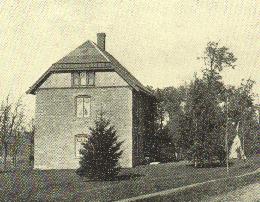

The

Old Queen Anne Parsonage, Fort Hunter, 1712 |

Chapter

VI: Queen Anne's Chapel

The

delegation spoken of in the last chapter was in England in the year 1708.

At an audience given them by Queen Anne, among other requests, they prayed

that Her Majesty should build them a fort and erect a church at their castle

at the junction of the Schoharie and Mohawk rivers, called Tiononderoga. This

she promised to do, and when Governor Robert Hunter arrived in New York in

1710 he carried with him instructions to build forts and chapels for the Mohawks

and Onondagas. These orders were carried out as far as the Mohawks were concerned

and the fort named Fort Hunter, but the Onondaga Chapel was never built.

The

contract for the construction of the fort was taken October 11, 1711, by Garret

Symonce, Barant and Hendrick Vrooman, Jan Wemp, and Arent Van Patten, all

of Schenectady.

The

walls were formed of logs, well pinned together, twelve feet high, the enclosure

being on hundred and fifty feet square. Surrounded by the palisades of the

fort and in the centre of the enclosure stood the historic edifice known as

Queen Anne's Chapel. It was erected by the builders of the fort, being, in

fact, part of their contract. It was built of limestone, was twenty-four feet

square, and had a belfry.

The

ruins of the fort were torn down at the beginning of the Revolution, and the

chapel surrounded by heavy palisades, block-houses being built at each corner,

on which cannon were mounted.

It

is said that soon after the erection of Queen Anne's Chapel the Dutch built

a long "meeting-house" near what was afterwards known as Snook's

Corners, but all trace of the building long ago disappeared. The first missionaries

to the Mohawks of whom we can find any account, who, under, the auspices of

the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, connected

with the Church of England, sent out to teach the Indians, were the Rev. Mr.

Talbot, in 1702, followed shortly afterwards by the Rev. Thoroughgood Moore,

in 1704. It is said that the Rev. Mr. Moore was driven away from Tiononderoga

by the Indian traders and went to New Brunswick, Connecticut. He was so scandalized

at the conduct of Governor Cornby and the Lieutenant-Governor to approach

the table of the Lord's Supper, for which act he was arrested and imprisoned

in jail. He succeeded in escaping and took passage in a vessel sailing for

England. As the vessel never reached its destination, it is supposed to have

foundered in mid-ocean and all on board lost.

The

Rev. Thomas Barclay, chaplain of Fort Orange, in the city of Albany, was then

called. He labored among the Mohawks from 1708 to 1712, and was, in 1712,

succeeded by the Rev. William Andrews. The parsonage or manse was built in

1712. The next record we find regarding Queen Anne's Chapel, is the purchase

or grant from the Crown of a tract of land containing three hundred acres.

This was called the Barclay tract and was granted to the Rev. Henry Barclay,

November 27, 1741, presumably for the benefit of Queen Anne's Chapel, and

was afterwards known as Queen Anne's Chapel, "glebe," the term glebe

being used to denote lands belonging to, or yielding revenue to a parish church,

an ecclesiastical benefice.

The

records say that the Rev. Mr. Andrews was no more successful than his predecessors,

and in 1719 abandoned his mission. The most cordial relations existed between

the ministers of the Reformed Dutch church, who also sent missionaries from

Albany to the Mohawk Indians, and the Episcopal Church in their Indian mission

work. After the Rev. Mr. Andres abandoned his mission, the Church of England

had no resident missionary among the Mohawks until the Rev. Henry Barclay

came in 1735, being appointed catechist to the Indians at Fort Hunter. His

stay with them was made very uncomfortable by the French war and the attitude

of his neighbors. He had no interpreter and but poor support, and his life

was frequently in danger. In 1745 he was obliged to leave Fort Hunter and

in 1746 was appointed rector of Trinity Church, New York, where he died. The

Rev. John Ogilvie was Dr. Barclay's successor. He commenced his work in March,

1749, and succeeded Dr. Barclay also at Trinity Church, New York, after the

latter's death in 1764. Queen Anne's Chapel seems to have been a stepping-stone

to the rectorship of Trinity Church.

Sir

William Johnson and the Rev. Mr. Inglis, of New York, obtained from the Society

for the Propagation of the Gospel in the year 1770, the Rev. John Stuart,

as missionary for service at Queen Anne's Chapel and vicinity.

The

Rev. John Stuart was a man of gigantic size and strength --over six feet high--called

by the Mohawks "the little gentleman." He preached his first sermon

at Indian Castle on Christmas Day, 1770. He had a congregation at the chapel

of two hundred persons and upwards. In 1774 he was able to read the liturgy

and the several offices of baptism, marriages, etc., to his flock in the language

of the Mohawks.

This

practically is the end of our knowledge of Queen Anne's Chapel as a church.

When we hear from it again it will be as a ruin.

Right

here it may be well to give a description of the same, as a church. We already

know that it was built of limestone, was twenty-four feet square, and had

a belfry. It also had a bell which was afterward placed in an institution

of learning at Johnstown and did good service for a number of years until

the building and the bell were destroyed by fire a few years ago.

The

entrance to the chapel was in the north side. The pulpit stood at the west

and was provided with a sounding-board. There was also a reading desk. Directly

opposite the pulpit were two pews with elevated floors, one of which, with

a wooden canopy, in later times was Sir William Johnson's; the other was for

the minister's family. The rest of the congregation had movable benches for

seats. The chapel had a veritable organ, the very Christopher Columbus of

its kind, in all probability the first instrument of music of such dignity

in all the wilderness west of Albany. It was over fifty years earlier than

the erection of the Episcopal church at Johnstown, which had an organ brought

from England, of very respectable size and great sweetness of tone, which

continued in use up to the destruction of the church by fire in 1836. Queen

Anne sent as furniture for the chapel:

-

A

communion table-cloth.

-

Two

damask napkins.

-

A

carpet for the communion table.

-

An

altar cloth.

-

A

small tasseled cushion for the pulpit.

-

One

Holland surplice.

-

A

small cushion for the desk.

-

One

large Bible.

- Two common

prayer books.

- One common

prayer book for the clerk.

- A book of

homilies.

- One large

silver flagons.

- One silver

dish.

- One silver

chalice.

- Four paintings

of Her Majesty's arms on canvas, one for the chapel and three for the different

Mohawk castles.

- Twelve large

octavo Bibles bound for use of the chapels among the Mohawks and Onondagas.

- Two painted

tables containing the Lord's Prayer, Creed, and Ten Commandments, "at

more than twenty guineas expense."

- A candelabrum,

with nine sockets, arranged in the form of a triangle, an emblem of the Trinity,

and a cross, both of brass, were in the parsonage many years, but, regarded

as useless, were, in our late civil war, melted and sold for old metal.

In 1877 the

Manse was still standing and in a fair state of preservation, though parts of

the woodwork shoed signs of decay. At the present time it has the appearance

of a very durable stone building with main entrance to the south. It is two

stories high and about twenty-five by thirty-five feet in size. The walls are

thick, making the recesses of the quaint old windows very deep, the glass being

six by eight and the sash in one piece. The glass for the windows and the bricks

for the single large chimney were brought from Holland. On the east end of the

building and over the cellar arch the characters "1712" are still

legible.

In 1888 the

late owner, Mr. DeWitt Devendorf, repaired the old parsonage and tore down the

old chimney and very thoughtfully presented about fifty of the old Dutch brick

to St. Ann's Church, Amsterdam, N. Y., the lineal descendant of Queen Anne's

Chapel and the principal recipient of the fund derived from the sale of the

old glebe farms.

On June 8, 1790,

Rev. Mr. Ellison preached at Fort Hunter. He says: "The church is in a

wretched condition, the pulpit, reading-desk, and two of the pews only being

left, the windows being destroyed, the floor demolished, and the walls cracked."

Except on a

few occasions by the Rev. Mr. Dempster, the chapel had not been used for a number

of years, when it was demolished about the year 1820, to give place to the Erie

Canal. The roof was burned off to get its stone walls, the stone being used

in constructing guard-locks for the canal near its site. It is said that the

beginning of the Revolution the silver service, curtains, fringes, gold lace,

and other fixtures of the chapel were put in a hogshead by the Mohawks and buried

on the side of the hill south of the Boyd Hudson Place near Auriesville, N.

Y. At the close of the war, when found by sounding with irons rods, it was discovered

that the silver service had been removed and the cask reburied, but by whom

or when it was never known. Most of the articles were so damaged by moisture

as to be unfit for use.

The question

is often asked why was not the old canal constructed in the same straight line

that the new canal follows in passing through Fort Hunter? At the time the old

canal was built, about 1820, there was a bridge across the Schoharie just above

the chapel, and the channel was diverted from a straight line, passed through

the site of the chapel, and the building destroyed in order to make use of the

bridge in towing the boats across the stream at this point, as it was deemed

more economical to destroy this historic landmark than go to the expense of

building a new bridge.

Commenting upon

this act at the present time we call it vandalism, but you must remember that

in those days there were no churchmen in that locality, locality, and that its

roof had been a "refuge from the storm" for the sheep and cattle that

were pastured on the land near by. For years the voice of prayer and thanksgiving

had been hushed, and instead of the solemn notes of the deep-toned organ within

walls that had echoed alike to the song of praise and the war cry of the Mohawks,

naught was heard but the lowing of cattle and the plaintive call of the sheep

for its young. We condemn this act of vandalism, but are we in our day any more

careful to preserve the old landmarks around which cling so many sweet and tender

memories.

With the assistance

of Trinity Church, New York, an Episcopal church was erected in 1835 at Port

Jackson, (the present fifth ward of Amsterdam, N. Y.), and maintained with the

assistance of funds derived from the sale of Queen Anne Chapel glebe farms.

This church was named St. Ann.

The church of

Port Jackson seems to have had a hard struggle for existence, probably on account

of its locality. During the rectorship of Rev. A. N. Littlejohn (the lately

deceased Bishop of Long Island) the edifice was sold and steps taken to erect

a stone building on Division Street, Amsterdam, N. Y.

The building

of this little stone church marked an era in church building in Amsterdam, which

previous to its erection were of the plain, unpretentious style of the fore

part of the nineteenth century. Even in its unfinished state, no one could look

at its gray walls and the Gothic arches without seeing its possibilities for

beauty when completed. The building of 1851 was of Gothic style, the nave only

being constructed. A wide aisle in the center led up to the narrow chancel in

the north end. The chancel rail enclosed the altar-table with a modest reredos

behind it and the reading-desk on the west side of it. Outside of the rail,

and a little in advance from it on the east side, stood a small octagonal elevated

pulpit. In the rear, or south end, of the church and over the vestibule, the

choir was located. The first organ, purchased in 1841, was bought in New York

City, was second hand, and the name of the maker has been forgotten. A new organ

was purchased in 1874 of Johnson and Co., Westfield, Mass., for $1500. This

organ is still in use in the new church.

The present

edifice was repaired and enlarged in 1888 to accommodate a largely increased

congregation. The interior is spacious, the whole depth being about one hundred

and thirty feet, and width sixty-five feet, with name, north and south aisles,

and choir. It is lighted with numerous windows painted to represent scenes in

the life of Christ and emblems of Christianity. All, or nearly all, of the windows

are in memoriam and are beautifully executed.

Approaching

the church from the east the eye rests on the green, well-kept law, with here

and there a tall maple of elm springing from it surface in pleasing irregularity.

Through their branches we catch a glimpse of the little stone church and tower,

which partially hides from view the main body of the edifice. Then we see a

portion of the stone pillars of a Grecian porch with its iron railings and gateway.

A few steps more and the panorama is complete and the whole south front of the

church is in view. The gray walls of the older portion when compared to the

completed church is "as moonlight unto sunlight and as water unto wine."

The dull red

of the superstructure, the rough ashler of the gray stone walls peeping through

the dense foliage of the Japanese ivy, the green carpet of the lawn, dotted

here and there with trees of venerable age, whose branches "half conceal

yet half reveal" the grandeur of the completed edifice, make a picture

that no artist can ever reproduce.

As the visitor

enters the church at the western or main entrance, the heavy oaken doors and

bare stone walls of the vestibule impress one with the idea of solidity, and

the view of the interior after passing the swinging baize doors, is in a degree

a surprise. The low aisles on each side with slender pillars, and the lofty

name with its graceful arches, with colors of gray and brown, and blue and brilliant

tints of the beautiful windows, give a feeling of rest to the beholder; and

as the eye wanders and is finally held by the graceful choir, a little somber

perhaps, in the distance, relieved somewhat by the glitter of lectern and pulpit,

its churchliness impresses one,and the thought of the visitor might well be,

"truly this is the house of God."

From Oronhyatekha,

the Supreme Chief Ranger of the Foresters of Canada and descendant from the

Mohawks of Tiononderoga, and from Rev. R. Ashton, the present incumbent of the

Mohawk Church at Brantford, Ontario, Canada, I have received the following information:

It appears that

the communion service that Queen Anne sent to the Mohawks was buried on their

old reservation at Fort Hunter during the Revolution, and remained there some

years or until the Mohawks became settled in the reservation near Brantford

(1785), and on the Bay of Quinte; then a party was sent back, resurrected the

plate, and brought it back to Canada. For a period of twenty-two years prior

to July, 1897, the plate was safely kept by Mrs. J. M. Hill, the granddaughter

of the celebrated chief, Capt. Joseph Brant, whose mother was the original custodian,

having kept it from the time of its arrival in Canada till her death.

Of course the

custodian was required to take the communion plate to the church on communion

days.

Later the Mohawks

were presented with a communion days, after which Queen Anne plate was only

used on state occasions.

In 1785 some

of the Mohawks settled at the Bay of Quinte and the larger body on Grand River,

Brantford. The Rev. John Stuart, D.D., who had been their missionary at Fort

Hunter and fled to Canada with the Indians and Tories, was appointed to the

charge of both bands, and a church was built at both places by King George III.

The plate was then divided; it consisted of seven pieces, two flagons, two chalices,

two patens, and one alms basin.

To the Grand

River band was given the alms basin and one each of the other pieces, also a

large Bible.

The Indians

at the Bay of Quinte have a flagon, paten, and chalice in the hands of Mrs.

John Hill, at Deseronto, Canada. The chalice at Grand River is much bent, the

other pieces are in good order, as is also the Bible. Each piece of plate is

inscribed: "The Gift of Her Majesty Ann, by the Grace of God, of Great

Britain, France and Ireland and Her Plantations in North American, Queen, to

Her Indian Chappel of the Mohawks." The Bible, printed in 1701, is in good

condition and bears on the cover, "For Her Majesty's Church of the Mohawks,

1712."

This plate has

a value aside from its intrinsic value, as explained by Rev. R. Ashton:

You are probably

aware that all pure silver plate manufactured in England is stamped by the government,

which stamp is called the "hall mark," which indicates that the article

is of standard silver or standard gold. From March, 1696, to June 1720, Britannia

and the lion's head erased, were substituted for leopard's head crowned and

the lion passant on silver, which both before and since have been in use as

the "hall mark." All silver bearing the former mark (and it is plainly

seen on every piece of the Mohawk and Onondaga silver), is greatly prized, and

is termed Queen Anne silver.

Copyright

© 1998, --

2003. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All

items on the site are copyrighted. While

we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying

it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted

and not to be reproduced

for distribution, sale, or profit.