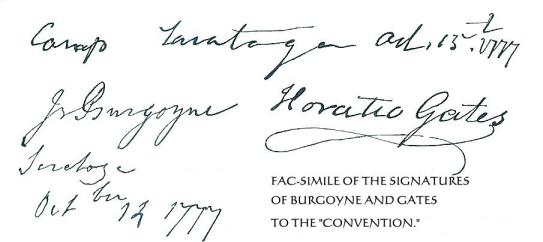

80

nimity of feeling which drew forth the expressed admiration

of Burgoyne and his officers, had ordered all his army within his camp,

out of sight of the vanquished Britons.(1) Colonel Wilkinson, who had been

sent to the British camp, and, in company with Burgoyne, selected the place

where the troops were to lay down their arms, was the only American officer

present at the scene.(2)

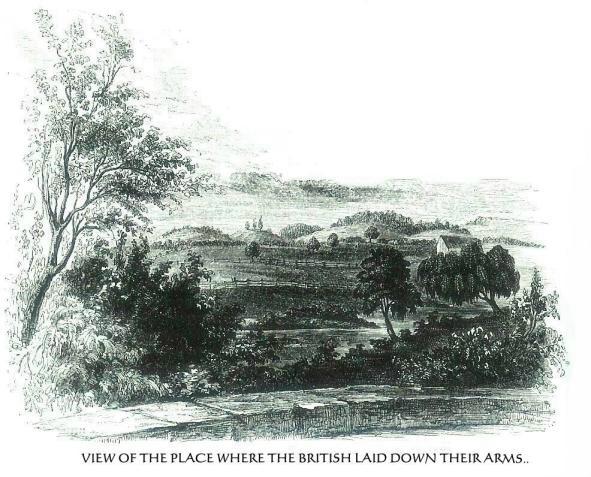

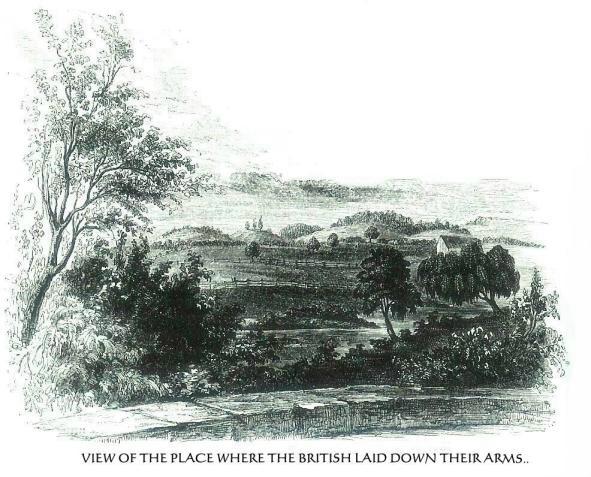

The sketch here presented, of the place where the British army surrendered,

was made from one of the canal bridges at Schuylerville, looking east-northeast.

The stream of water in the fore-ground is Fish Creek, and the level ground

seen between it and the distant hills on the left is the place where the

humiliation of the Britons occurred. The tree by the fence, in the center

of the picture, designates the northwest angle of Fort Hardy, and the other

three trees on the right stand nearly on the line of the northern breast-works.

The row of small trees, apparently at the foot of the dIstant hills, marks

the course of the Hudson; and the hills that bound the view are those on

which the Americans were posted. This plain is directly in front of Schuylerville,

between that village and the Hudson. General Fellows was stationed upon

the high ground seen over the barn on the right, and the eminence on the

extreme left is the place whence the American cannon played upon the house

wherein the Baroness Reidesel and other ladies sought refuge.

As soon as the troops had laid down their arms, General Burgoyne proposed

to be introduced to General Gates. They crossed Fish Creek, and proceeded

toward headquarters, Burgoyne in front with his adjutant general, Kingston,

and his aids-de-camp, Captain Lord Petersham and Lieutenant Wilford, behind

him. Then followed Generals Phillips, Riedesel, and Hamilton, and other

officers and suites, according to rank. General Gates was informed of the

approach of Burgoyne, and with his staff met him at the head of his camp,

about a mile south of the Fish Creek, Burgoyne in a rich uniform of scarlet

and gold, and! Gates in a plain blue frock-coat. When within about a sword's

length, they reined up and halted. Colonel Wilkinson then named the gentlemen,

and General Burgoyne, raising his hat gracefully, said, "The fortune

of war, General Gates, has made me your prisoner." The victor promptly

replied, "I shall always be ready to bear testimony that it has not

1 Letter or Burgoyne to the Earl or Derby. Stedman, i.,

352. Botta, ii., 21

2 See Wilkinson.

81

been through any fault of your excellency." The other officers were

introduced in turn, and the whole party repaired to Gates's headquarters,

where a sumptuous dinner was served.(1)

After dinner the American army was drawn up in parallel lines on each

side of the road, extending nearly a mile. Between these victorious troops

the British army, with light infantry in front, and escorted by a company

of light dragoons, preceded by two mounted officers bearing the AmerIcan

flag, marched to the lively tune of Yankee Doodle. (3) Just as they passed,

the two commanding generals, who were in Gates's marquee, came out together,

and, fronting the procession, gazed upon it in silence a few moments. What

a contrast, in every particular, did the two present! Burgoyne, though possessed

of coarse features, had a large and commanding person; Gates was smaller

and far less dignified in appearance. Burgoyne was arrayed in the splendid

military trappings of his rank; Gates was clad in a plain and unassuming

dress. Burgoyne was the victim of disappointed hopes and foiled ambition,

and looked upon the scene with exceeding sorrow; Gates was buoyant with

the first flush of a great victory. Without exchanging a word, Burgoyne,

according to previous understanding, stepped back, drew his sword, and,

in the presence of the two armies, presented it to General Gates. He received

it with a courteous inclination of the head, and instantly returned it to

the vanquished general. They then retired to the marquee together, the British

army filed off and took up their line of march for Boston, and thus ended

the drama upon the heights of Saratoga.

The whole number of prisoners surrendered was five thousand seven hundred

and ninety one, of whom two thousand four hundred and twelve were Germans

and Hessians. The force of the Americans, at the time of the surrender,

was, according to a statement which General Gates furnished to Burgoyne,

thirteen thousand two hundred and twenty-two, of which number nine thousand

and ninety-three were Continentals, or regular soldiers, and four thousand

one hundred and twenty-nine were militia. The arms and ammunition which

came into the possession of the Americans were, a fine train of brass artillery,

consisting of 2 twenty-four pounders, 4 twelve pounders, 20 sixes, 6 threes,

2 eight inch howitzers, 5 five and a half inch royal howitzers, and 3 five

and a half inch royal mortars; 4 in all forty-two

1 See Wilkinson.

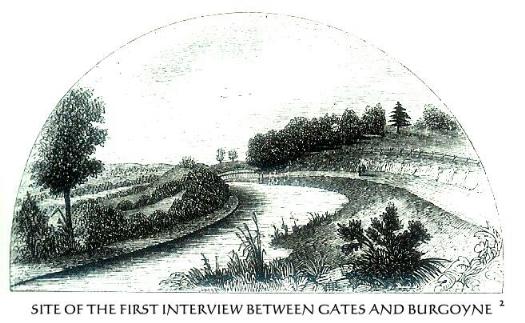

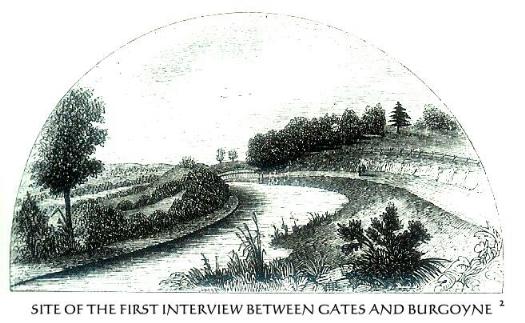

2 This view is taken from the turnpike, looking south. The old road was

where the canal now is, and the place of meeting was about at the point

where the bridge is seen.

3 Thatcher, in his Military Journal (p. 19), gives the following account

of the origin of the word Yank.ee and of Yankee Doodle: "A farmer of

Cambridge, Massachusetts, named Jonathan Hastings, who lived about the year

1713, used it as a favorite cant word to express excellence, as a yankee

good horse or yankee good cider. The students of the college, hearing him

use it a great deal, adopted it, and called him Yankee Jonathan; and as

he was a rather weak man, the students, when they wished to denote a character

of that kind, would call him Yankee Jonathan. Like other cant words, it

spread, and came finally tv be applied to the New Englanders as a term of

reproach. Some suppose the term to be the Indian corruption of the word

English-Yenglees, Yangles, Yankles, and finally Yankee.

" A song, called Yankee Doodle, was written by a British sergeant at

Boston, in 1775, to ridicule the people there, when the American army, under

Washington, was encamped at Cambridge and Roxbury," See "Origin

of Yankee Doodle," page 480, of this volume.

4 Two of these, drawings of which will be found on page 700, are now in

the court of the laboratory of the West Point Military Academy, on the Hudson.

82

pieces of ordnance. There were four thousand six hundred and forty-seven

muskets, and six thousand dozens of cartridges, besides shot, carcasses,

cases, shells, &c. Among the English prisoners were six members of Parliament.(1)

Contemporary writers represent the appearance of the poor German and Hessian

troops as extremely miserable and ludicrous. They deserved commiseration,

but they received none. They came not here voluntarily to fight our people;

they were sent as slaves by their masters, who received the price of their

hire. They were caught, it is said, while congregated in their churches

and elsewhere, and forced into the service. Most of them were torn reluctantly

from their families and friends; hundreds of them deserted here before the

close of the war; and many of their descendants are now living among us.

Many had their wives with them, and these helped to make up the pitiable

procession through the country. Their advent into Cambridge, near Boston,

is thus noticed by the lady of Dr. Winthrop of that town, in a letter to

Mrs. Mercy Warren, ail early historian of our Revolution: "On Friday

we heard the Hessians were to make a procession on the same route. We thought

we should have nothing to do but view them as they passed. To be sure, the

sight was truly astonishing. I never had the least idea that the creation

produced such a sordid set of creatures in human figure-poor, dirty, emaciated

men. Great numbers of women, who seemed to be the beasts of burden, having

bushel baskets on their backs, by which they were bent double. The contents

seemed to be pots and kettles, various sorts of furniture, children peeping

through gridirons and other utensils. Some very young infants, who were

born on the road; the women barefooted,.clothed in dirty rags. Such effluvia

filled the air while; they were passing, that, had they not been smoking

all the time, I should have been apprehensive of being contaminated."(2)

The whole view of the vanquished army, as it marched through the country

from Saratoga to Boston, a distance of three hundred miles, escorted by

two or three American officers and a handful of soldiers, was a spectacle

of extraordinary interest. Generals of the first order of talent; young

gentlemen of noble and wealthy families, aspiring to military renown; legislators

of the British realm, and a vast concourse of other men; lately confident

of victory and of freedom to plunder and destroy, were led captive through

the pleasant land they had cove ed, to be gazed at with mingled joy and

scorn by those whose homes they came to make desolate. " Their march

was solemn, sullen, and silent; but they were every where treated with such

humanity, and even delicacy, that they were. overwhelmed with astonishment

and gratitude. Not one insult was offered, not an opprobrious reflection

cast ;"(3)and in all their long captivity(4) they experienced the generous

kindness of a people warring only to be free.

1 Gordon, ii., 267.

2 Women of the Revolution, i., 97. 3 Mercy Warren, ii., 40.

3 Although Congress ratified the generous terms entered into by Gates with

Burgoyne in the convention at Saratoga, circumstances made them suspicious

that the terms would not be strictly complied with. They feared that the

Britons would break their parole, and Burgoyne was required to furnish a

complete roll of his army, the name and rank of every officer, and the name,

former place of abode, occupation, age, and size of every non-commissioned

officer and private soldier. Burgoyne murmured and hesitated. General Howe,

at the same time, was very illiberal in the exchange of prisoners, and exhibited

considerable duplicity. Congress became alarmed, and resolved not to allow

the army of Burgoyne to leave our shores until a formal ratification of

the convention should be made by the British government. Burgoyne alone

was allowed to go home on parole, and the other officers, with the army,

were marched into the interior of Virginia, to await the future action of

the two governments. The British ministry charged Congress with positive

perfidy, and Congress justified their acts by charging the ministers with

meditated perfidy. That this suspicion was well founded is proved by subsequent

events. In the autumn of 1778, Isaac Ogden, a prominent loyalist of New

Jersey, and then a refugee in New York, thus wrote to Joseph Galloway, an

American Tory in London, respecting an expedition of four thousand British

troops which Sir Henry Clinton sent up the Hudson a week previous: "Another

object of this expedition was to open the country for many of Burgoyne's

troops that had escaped the vigilance of their guard, to come in. About

forty of these have got safe in. If this expedition had been a week sooner,

greater part of Burgoyne's troops probably would have arrived here, as a

disposition of rising on their guard strongly prevailed, and all they wanted

to effect it was some support near at hand."

83

The surrender of Burgoyne was an event of infinite importance to the struggling

republicans. Hitherto the preponderance of success had been on the side

of the English, and only a few partial victories had been won by the Americans.

The defeat on Long Island had eclipsed the glory of the siege of Boston;

the capture of Fort Washington and its garrison had overmatched the brilliant

defense of Charleston; the defeat at Brandywine had balanced the victory

at Trenton; White Plains and Princeton were in fair juxtaposition in the

account current; and at the very time when the hostile armies at the north

were fighting for the mastery, Washington was suffering defeats in Pennsylvania,

and Forts Clinton, Montgomery, and Constitution were passing into the hands

of the royal forces. Congress had lied from Philadelphia to York, and its

sittings were in the midst of loyalists, ready to attack or betray. Its

treasury was nearly exhausted; its credit utterly so. Its bills to the amount

of forty millions of dollars were scattered over the country. Its frequent

issues were inadequate to the demands of the commissariat, and distrust

was rapidly depreciating their value in the public mind. Loyalists rejoiced;

the middlemen were in a dilemma; the patriots trembled. Thick clouds of

doubt and dismay were gathering in every part of the political horizon,

and the acclamations which had followed the Declaration of Independence.

the year before, died away like mere whispers upon the wind.

All eyes were turned anxiously to the army of the north, and upon that

strong arm of Congress, wielded, for the time, by Gates, the hopes of the

patriots leaned. How eagerly they listened to every breath of rumor from

Saratoga! How enraptured were they when the cry of victory fell upon their

ears! All over the land a shout of triumph went up, and from the furrows,

and workshops, and marts of commerce; from the pulpit, from provincial halls

of legislation, from partisan camps, and from the shattered ranks of the

chief at White Marsh, it was echoed and re-echoed. Toryism, which had begun

to lift high its head, retreated behind the defense of inaction; the bills

of Congress rose twenty per cent. in value; capital came forth from its

hiding-places; the militia readily obeyed the summons to the camp, and the

great patriot heart of America beat strongly with pulsations of hope. Amid

the joy of the moment, Gates was apotheosized in the hearts of his countrymen,

mid they

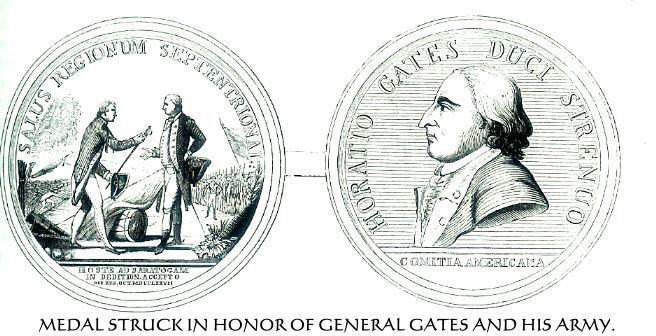

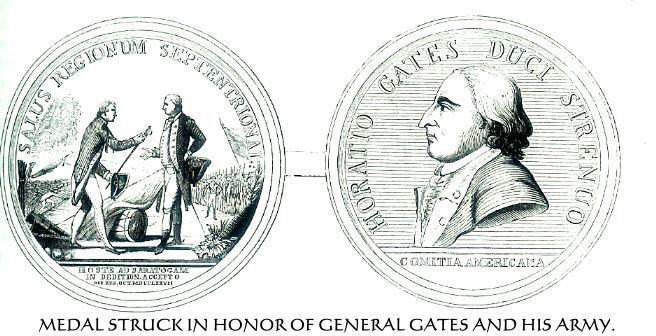

The engraving exhibits a view of both sides of the medal,

drawn the size of the original. On one side is a bust of General Gates,

with the Latin inscription, "HORATIO GATES DUCl STRENUO COMITIA AMERICANA;"

The American Congress, to Heratio Gates, the valiant leader. On the other

side, Of reverse, Burgoyne is represented in the attitude of delivering

up his sword and in the background, on either side or them, are seen the

two armies of England and America, the former laying down their arms. At

the top is the Latin inscription, "SALUS REGIONUM SEPTENTRIONAL ,"

literal English, Safety of the northern region or department. Below is the

inscription, "HOSTE AD SARATOGAM IN DEDITION, ACCEPT O DIE xvii. OCT.

MI CCLXXVII;" English, Enemy at Saratoga surrendered October 17th,

1777.

94

generously overlooked the indignity offered by him to the commander-in-chief

when he refused, in the haughty pride of his heart in that hour of victory,

to report, as in duty bound, his success to the national council through

him. Congress, too, overjoyed at the result, forgot its own dignity, and

allowed Colonel Wilkinson,(1) the messenger of the glad tidings, to stand

upon their floor and proclaim, "The whole British army have laid down

their arms at Saratoga; our own, full of vigor and courage, expect your

orders; it is for your wisdom to decide where the country may still have

need of their services." Congress voted thanks to General Gates and

his army, and decreed that he should be presented with a medal of gold,

to be struck expressly in commemoration of so glorious a victory.

This victory was also of infinite importance to the republicans on account

of its effects beyond the Atlantic. The highest hopes of the British nation,

and the most sanguine expectations of the king and his ministers, rested

on the success of this campaign. It had been a favorite object with the

administration, and the people were confidently assured that, with the undoubted

success of Burgoyne, the turbulent spirit of rebellion would be quelled,

and the insurgents would be forced to return to their allegiance.

Parliament was in session when the intelligence of Burgoyne's defeat reached

England; (December 3, 1777.) and when the mournful tidings were communicated

to that body, it instantly aroused all the fire of opposing parties.(2)The

opposition opened anew their eloquent batteries upon the ministers. For

several days misfortune had been suspected. The last arrival from America

brought tidings of gloom. The Earl of Chatham, with far-reaching comprehension,

and thorough knowledge of American affairs, had denounced the mode of warfare

and the material used against the Americans. He refused to vote for the

laudatory address to the king. Leaning upon his crutch, he poured forth

his vigorous denunciations against the course of the ministers like a mountain

torrent. " This, my lords," he said, "is a perilous and tremendous

moment! It is no time for adulation. The smoothness of flattery can not

now avail-can not save us in this rugged and awful crisis. It is now necessary

to instruct the throne in the language of truth. . . . . . . . . You can

not. I venture to say it, you can not conquer America. What is your present

situation there? We do not know the worst, but we know that in three campaigns

we have suffered much and gained nothing, and perhaps at this moment the

northern army (Burgoyne's) may be a total loss. . . . . . . . . You may

swell every expense, and every effort, still more extravagantly; pile and

accumulate every assistance you can buy or borrow; traffic and barter with

every little pitiful German prince that sells and sends his subjects to

the shambles of a foreIgn power; your efforts are forever vain and impotent;

doubly so from this mercenary aid on which you rely, for it irritates to

an incurable resentment the minds of your enemies. To overrun with the mercenary

sons of rapine and plunder, devoting them and their possessions to the rapacity

of hireling cruelty! If I were an American, as I am an Englishman, while

a foreign troop was landed in my country, I never would lay down my arms-never,

never, never !"(3)

The Earl of Coventry, Earl Temple Chatham's brother-in-law, and the Duke

of Richmond, all spoke in coincidence with Chatham. Lord Suffolk, one of

the Secretaries of State, undertook the defense of ministers for the employment

of Indians, and concluded by saying, " It is perfectly justifiable

to use all the means that God and nature have put into our hands."

This sentiment brought Chatham upon the floor. "That God and nature

put

1 James Wilkinson was born in Maryland about 1757, and,

by education, was prepared for the practice of medicine. He repaired to

Cambridge as a volunteer In 1775. He was captain of a company in a regiment

that went to Canada in 1776. He was appointed deputy adjutant general by

Gates, and, after the surrender of Burgoyne, Congress made him a brigadier

general by brevet. At the conclusion of the war he settled in Kentucky,

but entered the army in 1806, and had the command on the Mississippi. He

commanded on the northern frontier during our last war with Great Britain.

A t the age of 56 he married a young lady of 26. He died of diarrhea, in

Mexico, December 28th, 1825, aged 68 years.

2 Pitkin, i., 399.

3 Parliamentary Debates.

85

into our hands!" he reiterated, with bitter scorn. "I know not

what idea that lord may entertain of God and nature, but I know that such

abominable principles are equally abhorrent to religion and humanity. What!

attribute the sacred sanction of God and nature to the massacres of the

Indian scalping-knife, to the cannibal and savage, torturing, murdering.

roasting, and eating-literally, my lords, eating-the mangled victims of

his barbarous battles. . . . . . . . . These abominable principles, and

this most abominable avowal of them, demand most decisive indignation. I

call upon that right reverend bench (pointing to the bishops), those holy

ministers of the Gospel and pious pastors of the Church-I conjure them to

join in the holy work, and to vindicate the religion of their God."

In the Lower House, Burke, Fox, and Barre were equally severe upon the

ministers: and on the 3d of December, when the news of Burgoyne's defeat

reached London, the latter arose in his place in the Commons, and, with

a severe and solemn countenance, asked Lord George Germain, the Secretary

of War, what news he had received by his last expresses from Quebec, and

to say, upon his word of honor, what had become of Burgoyne and his brave

army. The haughty secretary was irritated by the cool irony of the question,

but he was obliged to unbend and to confess that the unhappy intelligence

had reached him, but added it was not yet authenticated.(1)

Lord

North, the premier, with his usual adroitness, admitted that misfortune

had befallen the British arms, but denied that any blame could be imputed

to ministers themselves, and proposed an adjournment of (December, 1777.)

Parliament on the 11th (which was carried) until the 20 of January.(2) It

was (1778.) a clever trick of the premier to escape the castigations which

he knew the opposition would inflict while the nation was smarting under

the goadings of mortified pride. The victory over Burgoyne, unassisted as

our troops were by foreign aid, placed the prowess of the United States

in the most favorable light upon the continent. Our urgent solicitations

for aid, hitherto but little noticed except by France, were now listened

to with respect, and the American commissioners at Paris. Dr. Franklin,

Silas Deane, (3) and Arthur Lee,(4) occupied a commanding position among

the diplomatists of Europe, France, Spain, the States General of Holland,

the Prince of Orange, and even Catharine of Russia and Pope Clement XIV.

(Ganganelli), all

Lord

North, the premier, with his usual adroitness, admitted that misfortune

had befallen the British arms, but denied that any blame could be imputed

to ministers themselves, and proposed an adjournment of (December, 1777.)

Parliament on the 11th (which was carried) until the 20 of January.(2) It

was (1778.) a clever trick of the premier to escape the castigations which

he knew the opposition would inflict while the nation was smarting under

the goadings of mortified pride. The victory over Burgoyne, unassisted as

our troops were by foreign aid, placed the prowess of the United States

in the most favorable light upon the continent. Our urgent solicitations

for aid, hitherto but little noticed except by France, were now listened

to with respect, and the American commissioners at Paris. Dr. Franklin,

Silas Deane, (3) and Arthur Lee,(4) occupied a commanding position among

the diplomatists of Europe, France, Spain, the States General of Holland,

the Prince of Orange, and even Catharine of Russia and Pope Clement XIV.

(Ganganelli), all

1 History of the Reign of George III., i., 326.

2 Pitkin, i., 391. Annual Register: 1178, p. 14.

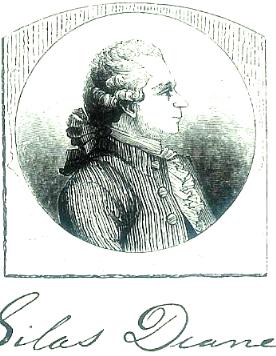

3 Silas Deane was a native of Groton, Connecticut. He graduated at Yale

College, 1158, and was a member of the first Congress, 1174. He was sent

to France Early in 1776, as political and commercial agent for the United

Colonies, and in the autumn of that year was associated with Franklin and

Lee as commissioner. He seems to have been unfit, in a great degree, for

the station he held, and his defective judgment and extravagant promises

greatly embarrassed Congress. He was recalled at the close of 1117. and

John Adams appointed in his place. He published a defense of his character

in 1118, and charged Thomas Paine and others connected with public affairs

with using their official influence for purposes of private gain. This was

the charge made against himself, and he never fully wiped out all suspicion.

He went to England toward the close of 1184, and died in extreme poverty

at Deal, 1789.

4 Dr. Lee was born in Virginia in 1140-a brother to the celebrated Richard

Henry Lee. He was educated at Edinburgh, and, on returning to America, practiced

medicine at Williamsburgh about five years. He went to London in 1166, and

studied law in the Temple. He kept his brother and other patriots of the

Revolution fully informed of all political matters of importance abroad,

and particularly the movements of the British ministry. He wrote a great

deal, and stood high as an essayist and political pamphleteer. He was colonial

agent for Virginia in 1115. In 1116 he was associated with Franklin and

Deane, as minister at the court of Versailles. He and John Adams were recalled

in 1119. On returning to the United States; he was appointed to offices

of trust. He died of pleurisy, December 14th, 1182, aged nearly 42.

86

of whom feared and hated England because of her increasing potency in arms,

commerce, diplomacy, and the Protestant faith, thought kindly of us and

spoke kindly to us. We were loved because England was hated; we were respected

because we could injure England by dividing her realm and impairing her

growing strength beyond the seas. There was a perfect reciprocity of service;

and when peace was ordained by treaty, and our independence was established,

the balance-sheet showed nothing against us, so far as the governments of

continental Europe were concerned.

In the autumn of 1776, Franklin and Lee were appointed, jointly with Deane.

(November.) resident commissioners at the court of amity and commerce with

with the French king. They opened negotiations early in December with the

Count De Vergennes, the premier of Louis XVI. He was distinguished for sound

wisdom, extensive political knowledge, remarkable sagacity, and true greatness

of mind. He foresaw that generous dealings with the insurgent colonists

at the outset would be the surest means of perpetuating the rebellion until

a total separation from the parent state would be accomplished-an event

eagerly coveted by the French government. France hated England cordially,

and feared her power. She had no special love for the Anglo-American colonies,

but she was ready to aid them in reducing, by disunion, the puissance of

the British empire. To widen the breach was the chief aim of Vergennes.

A haughty reserve, he knew, would discourage the Americans, while an open

reception, or even countenance, of their. deputies might alarm the rulers

of Great Britain, and dispose them to a compromise with the colonies, or

bring on an immediate rupture between France and England. A middle line

was, therefore, pursued by him. (1)

While the French government was thus vacillating during the first three

quarters of 1777, secret aid was given to the republicans, and great quantities

of arms and ammunition were sent to this country, by an agent of the French

government, toward the close of the year, ostensibly through the channel

of commercial operations.(2) But when the capture of

1 Ramsay, ii., 62, 63.

2 In the summer of 1776, Arthur Lee, agent of the Secret Committee of Congress,

made an arrangement by which the French king provided money and arms secretly

for the Americans. An agent named Beaumarehais was sent to London to confer

with Lee, and it was arranged that two hundred thousand Louis d'ors, in

arms, ammunition, and specie, should be sent to the Americans, but in a

manner to make it appear as a commercial transaction. Mr. Lee assumed the

name of Mary Johnson, and Beaumarchais that of Roderique, Hortales, &

Co. Lee, fearing discovery if he should send a written notice to Congress

or the arrangement, communicated the fact verbally through Captain Thomas

Story, who had been upon the continent in the service of the Secret Committee.

Yet, after all the arrangements were made, there was hesitation, and it

was not until the autumn of 1777 that the articles were sent to the Americans.

They were shipped on board Le Henreux, in the fictitious name of Hortales,

by the way of Cape Francois, and arrived at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on

the 1st of November of that year. The brave and efficient Baron Steuben

was a passenger in that ship.

This arrangement, under the disguise of a mercantile operation, subsequently

produced a great deal of trouble, a more minute account of which is given

in the Supplement to this work.

Beaumarchais was one of the most active business men of his time, and became

quite distinguished in the literary and political world by his "Marriage

of Figaro," and his connection with the French Revolution in 1793.

Borne, in one of his charming Letters from Paris, after describing

his visit to the house where Beaumarchais had lived, where "they now

sell kitchen salt," thus speaks of him: "By his bold and fortunate

commercial undertakings, he had become one or the richest men in France.

In the war of American liberty, he furnished, through an understanding with

the French government, supplies of arms to the insurgents. As in all such

undertakings, there were captures, shipwrecks, payments deferred or refused,

yet Beaumarchais, by his dexterity, succeeded in extricating himself with

personal advantage from all these difficulties.

" Yet this same Beaumarchais showed himself, in the (French) revolution,

as inexperienced as a child and as timid as a German closet. scholar. He

contracted to furnish weapons to the revolutionary government, and not only

lost his money, but was near losing his head into the bargain. Formerly

he had to deal with the ministers of an absolute monarchy. The doors of

great men's cabinets open and close softly and easily to him who knows how

to oil the locks and hinges. Afterward Beaumarchais had to do with honest,

in other words with dangerous people; he had not learned to make the distinction,

and accordingly he was ruined." He died in 1799, in his 70th year,

and his death, his friends suppose, was voluntary.

87

Burgoyne and his army (intelligence of which arrived at Paris by express

on the 4th of December) reached Versailles, and the ultimate success of

the Americans was hardly problematical, Louis cast off all disguise, and

informed the American commissioners, through M. Gerard, one of his Secretaries

of State, that the treaty of alliance and commerce, already negotiated,

would be ratified, and" that it was decided to acknowledge the independence

of the United States." He wrote to his uncle, Charles IV. of Spain,

urging his co-operation; for, according to the family compact of the Bourbons,

made in 1761, the King of Spain was to be consulted before such a treaty

could be ratified.(1) Charles refused to cooperate, but Louis persevered,

and in February, 1778, he acknowledged the independence of the United States,

and entered into treaties of alliance and (February 6.) commerce with them

on a footing of perfect equality and reciprocity. War against England was

to be made a common cause, and it was agreed that neither contracting party

should conclude truce or peace with Great Britain without the formal consent

of the other first obtained; and it was mutually covenanted not to lay down

their arms until the independence or the United States should be formally

or tacitly assured by the treaty or trea.ties that should terminate the

war.(2) Thus allied, by treaty, with the ancient and powerful French nation,

the Americans felt certain of success.

1 This letter of Louis was brought to light during the Revolution

of 1793. It is a curious document, and illustrates the consummate duplicity

practiced by that monarch and his ministers. Disclosing, as it does, the

policy which governed the action of the French court, and the reasons which

induced the king to accede to the wishes of the Americans, its insertion

here will doubtless bc acceptable to the reader. It was dated January 8th,

1778.

"The sincere desire," said Louis, "which I feel of maintaining

the true harmony and unity of our system of alliance, which must always

have an imposing character for our enemies, induces me to state to your

majesty my way of thinking on the present condition of affairs. England,

our common and inveterate enemy, has been engaged for three years in a war

with her American colonies. We had agreed not to intermeddle with it, and,

viewing both sides as English, we made our trade free to the one that found

most advantage in commercial intercourse. In this manner America provided

herself with arms and ammunition, of which she was destitute; I do not speak

of the succors of money and other kinds which we have given her, the whole

ostensibly on the score of trade. England has taken umbrage at these succors,

and has not concealed from us that she will be revenged sooner or later.

She has already, indeed, seized several or our merchant vessels, and refused

restitution. We have lost no t.ime on our part. We have fortified our most

exposed colonies, and placed our fleets upon a respectable footing, which

has continued to aggravate the ill humor of England.

"Such was the posture of affairs in November last. The destruction

of the army of Burgoyne and the straitened condition of Howe have lately

changed the face of things. America is triumphant and England cast down;

but the latter has still a great, unbroken maritime force, and the hope

of forming a beneficial alliance with the colonies, the impossibility of

their being subdued by arms being now demonstrated. All the English parties

agree on this point. Lord North has himself announced in full Parliament

a plan of pacification for the first session, and all sides are assiduously

employed upon it. Thus it is the same to us whether this minister or any

other be in power. From different motives they join against us, and do not

forget our bad offices. They will fall upon us in as great strength as if

the war had not existed. This being understood, and our grievances against

England notorious, I have thought, after taking the advice or my council,

and particularly that of M. D'Ossune, and having consulted upon the propositions

which the insurgents make, to treat with them, to prevent their reunion

with the mother country. I lay before your majesty my views of the subject.

I have ordered a memorial to be submitted to you, in which they arc presented

in more detail. I desire eagerly that they should meet your approbation.

Knowing the weight of your probity, your majesty will-not doubt the lively

and sincere friendship with which I am yours," &c. Quoted by Pitkin

(i., 399) from Histoire, &c., de la Diplomatique Francaise, vol. vii.

2 Sparks's Life of Franklin, 430, 433.

Lord

North, the premier, with his usual adroitness, admitted that misfortune

had befallen the British arms, but denied that any blame could be imputed

to ministers themselves, and proposed an adjournment of (December, 1777.)

Parliament on the 11th (which was carried) until the 20 of January.(2) It

was (1778.) a clever trick of the premier to escape the castigations which

he knew the opposition would inflict while the nation was smarting under

the goadings of mortified pride. The victory over Burgoyne, unassisted as

our troops were by foreign aid, placed the prowess of the United States

in the most favorable light upon the continent. Our urgent solicitations

for aid, hitherto but little noticed except by France, were now listened

to with respect, and the American commissioners at Paris. Dr. Franklin,

Silas Deane, (3) and Arthur Lee,(4) occupied a commanding position among

the diplomatists of Europe, France, Spain, the States General of Holland,

the Prince of Orange, and even Catharine of Russia and Pope Clement XIV.

(Ganganelli), all

Lord

North, the premier, with his usual adroitness, admitted that misfortune

had befallen the British arms, but denied that any blame could be imputed

to ministers themselves, and proposed an adjournment of (December, 1777.)

Parliament on the 11th (which was carried) until the 20 of January.(2) It

was (1778.) a clever trick of the premier to escape the castigations which

he knew the opposition would inflict while the nation was smarting under

the goadings of mortified pride. The victory over Burgoyne, unassisted as

our troops were by foreign aid, placed the prowess of the United States

in the most favorable light upon the continent. Our urgent solicitations

for aid, hitherto but little noticed except by France, were now listened

to with respect, and the American commissioners at Paris. Dr. Franklin,

Silas Deane, (3) and Arthur Lee,(4) occupied a commanding position among

the diplomatists of Europe, France, Spain, the States General of Holland,

the Prince of Orange, and even Catharine of Russia and Pope Clement XIV.

(Ganganelli), all