There are still very prominent traces of the banks and fosse of the fort, but the growing village will soon spread over and obliterate them forever. Already a garden was within the lines; and the old parade-ground, wherein Sir William Johnson strutted in the haughty pride of a victor by accident,(1) was desecrated by beds of beets, parsley, radishes, and onions

Fort Edward was the theater of another daring achievement by Putnam. In the winter of 1756 the barracks, then near the northwestern bastion, took fire. The magazine was only twelve feet distant, and contained three hundred barrels of gunpowder. Attempts were made to batter the barracks to the ground with heavy cannons, but without success. Putnam, who was stationed upon Rogers's Island, in the Hudson, opposite the fort, hurried thither, and, taking his station on the roof of the barracks, ordered a line of soldiers to hand him water. But, despite his efforts, the flames raged and approached nearer and nearer to the magazine. The commandant, Colonel Haviland, seeing his danger, ordered him down; but the brave major did not leave his perilous post until the fabric began to totter. He then leaped to the ground, placed himself between the falling building and the magazine, and poured on water with all his might. The external planks of the magazine were consumed, and there was only a thin partition between the flames and the powder. But Putnam succeeded in subduing the flames and saving the ammunition. His hands and face were dreadfully burned, his whole body was more or less blistered, and it was several weeks before he recovered from the effects of his daring conflict with the fire.

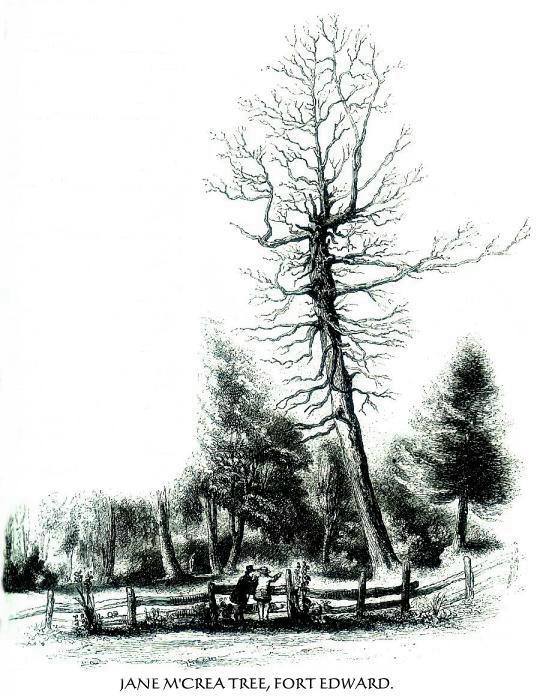

The first place of historic interest that we visited at Fort Edward was the venerable and blasted pine tree near which, tradition asserts, the unfortunate Jane M'Crea lost her life while General Burgoyne had his encampment near Sandy Hill. It stands upon the west side of the road leading from Fort Edward to Sandy Hill, and about half a mile from the canal-lock in the former village. The tree had exhibited unaccountable signs of decadence for several years, and when we visited it, it was sapless and bare. Its top was torn off by a November gale, and almost every breeze diminishes its size by scattering its decayed twigs. The trunk is about five feet in diameter, and upon the bark is engraved, in bold letters, JANE M'CREA, 1777. The names of many ambitious visitors are intaglioed upon it, and reminded me of the line "Run, run, Orlando, carve on every tree." I carefully sketched all its branches, and the engraving is a faithful portraiture of the interesting relic, as viewed from the opposite side of the road. In a few years this tree, around which history and romance have clustered so many associations, will crumble and pass away forever.(2)

The sad story of the unfortunate girl is so interwoven in our history that it has become a component part; but it is told with so many variations, in essential and non-essential par-

1 Sir William Johnson had command of the English forces

in 1755, destined to act against Crown Point. He was not remarkable for

courage or activity. He was attacked at the south end of Lake George by

the French general, Deiskau, and was wounded at the outset. The command

then devolved on Major-general Lyman, of the Connecticut troops, who, by

his skill and bravery, secured a victory over the French and Indians. General

Johnson, however, had the honor and reward thereof. In his mean jealousy

he gave General Lyman no praise; and the British king (George II.) made

him a baronet, and a present of twenty thousand dollars to give the title

becoming dignity.

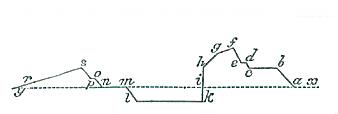

NOTE,-As

I shall have frequent occasion to employ technical terms used in fortifications,

I here give a diagram, which, with the explanation, will make those terms

clear to the reader, The figure is a vertical section of a fortification.

The mass of earth, a b c d e f g h, forms the rampart with

its parapet; a b is the interior slope of the rampart; b

c is the terre-plein of the rampart, on which the troops and

cannon are placed; d e is the banquette, or step, on which

the soldiers mount to fire over the parapet; e f g is the parapet;

g h is the exterior slope of the parapet; h i is the

revetment, or wall of masonry, supporting the rampart; h k,

the exterior front covered with the revetment is called the escarp;

i k l m is the ditch; l m is the counterscarp; m n is

the covered way, having a banquette n o p; s r is the

glacis. When there are two ditches, the works between the inner

and the outer ditch are called ravelins, and all outside of the

ditches, outworks,-See Brande's Cyc., art. Fortification.

NOTE,-As

I shall have frequent occasion to employ technical terms used in fortifications,

I here give a diagram, which, with the explanation, will make those terms

clear to the reader, The figure is a vertical section of a fortification.

The mass of earth, a b c d e f g h, forms the rampart with

its parapet; a b is the interior slope of the rampart; b

c is the terre-plein of the rampart, on which the troops and

cannon are placed; d e is the banquette, or step, on which

the soldiers mount to fire over the parapet; e f g is the parapet;

g h is the exterior slope of the parapet; h i is the

revetment, or wall of masonry, supporting the rampart; h k,

the exterior front covered with the revetment is called the escarp;

i k l m is the ditch; l m is the counterscarp; m n is

the covered way, having a banquette n o p; s r is the

glacis. When there are two ditches, the works between the inner

and the outer ditch are called ravelins, and all outside of the

ditches, outworks,-See Brande's Cyc., art. Fortification.

2 It was cut down in 1853, and converted into canes,

boxes, &c.

97

ticulars, that much of the narratives we have is evidently pure fiction; a simple take of Indian abduction, resulting in death, having its counterpart in a hundred like occurrences, has been garnished with all the high coloring of a romantic love story. It seems a pity to spoil the romance of the matter, but truth always makes sad havoc with the frost-work of the imagination, and sternly demands the homage of the historian's pen.

All

accounts agree that Miss M'Crea was staying at the house of a Mrs. M'Neil,

near the fort, at the time of the tragedy. A granddaughter of Mrs. M'Neil

(Mrs. F-n) is now living at Fort 1848. Edward, and from her I received a

minute account of the whole transaction, as she had heard it a "thousand

times" from her grandmother. She is a woman of remarkable intelligence,

about sixty years old. When I was at Fort Edward she was on a visit with

her sister at Glenn's Falls. It had been my intention to go direct to Whitehall,

on Lake Champlain, by way of Fort Ann, but the traditionary accounts in

the neighborhood of the event in question were so contradictory of the books,

and I received such assurances that perfect reliance might be placed upon

the statements of Mrs. F-n, that, anxious to ascertain the truth of the

matter, if possible, we went to Lake Champlain by way of Glenn's Falls and

Lake George. After considerable search at the falls, I found Mrs. F-n, and

the following is her relation of the tragedy at Fort Edward:

All

accounts agree that Miss M'Crea was staying at the house of a Mrs. M'Neil,

near the fort, at the time of the tragedy. A granddaughter of Mrs. M'Neil

(Mrs. F-n) is now living at Fort 1848. Edward, and from her I received a

minute account of the whole transaction, as she had heard it a "thousand

times" from her grandmother. She is a woman of remarkable intelligence,

about sixty years old. When I was at Fort Edward she was on a visit with

her sister at Glenn's Falls. It had been my intention to go direct to Whitehall,

on Lake Champlain, by way of Fort Ann, but the traditionary accounts in

the neighborhood of the event in question were so contradictory of the books,

and I received such assurances that perfect reliance might be placed upon

the statements of Mrs. F-n, that, anxious to ascertain the truth of the

matter, if possible, we went to Lake Champlain by way of Glenn's Falls and

Lake George. After considerable search at the falls, I found Mrs. F-n, and

the following is her relation of the tragedy at Fort Edward:

Jane M'Crea was the daughter of a Scotch Presbyterian clergyman of Jersey City, opposite New York; and while Mrs. M'Neil (then the wife of a former husband named Campbell) was a resident of New York City, an acquaintance and intimacy had grown up between Jenny and her daughter. After the death of Campbell (which occurred at sea) Mrs. Campbell married M'Neil. He, too, was lost at sea, and she removed with her family to an estate

98

owned by him at Fort Edward. Mr. M'Crea, who was a widower, died, and Jane went to live with her brother near Fort Edward, where the intimacy of former years with Mrs. M'Neil and her daughter was renewed, and Jane spent much of her time at Mrs. M'Neil's house. Near her brother's lived a family named Jones, consisting of a widow and six sons, and between Jenny and David Jones, a gay young man, a feeling of friendship budded and ripened into reciprocal love. When the war broke out the Joneses took the royal side of the question, and David and his brother Jonathan went to Canada in the autumn of 1776. They raised a company of about sixty men, under pretext of re-enforcing the American garrison at Ticonderoga, but they went further down the lake and joined the British garrison (June 1, 1777.) at Crown Point. When Burgoyne collected his forces at St. John's, at the foot of Lake Champlain, David and Jonathan Jones were among them. Jonathan was made a captain and David a lieutenant in the division under General Fraser, and at the time in question they were with the British army near Sandy Hill. Thus far all accounts nearly agree.

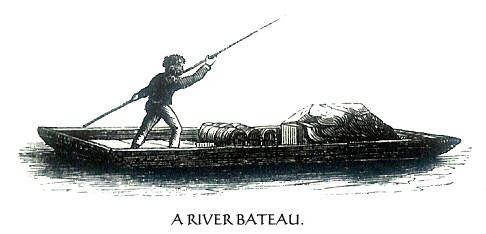

The brother of Jenny was a Whig, and prepared to move to Albany; but Mrs. M'Neil, who was a cousin of General Fraser (killed at Stillwater), was a stanch loyalist, and intended to remain at Fort Edward. When the British were near, Jenny was at Mrs. M'Neil's, and lingered there even after repeated solicitations from her brother to return to his house, five miles further down the river, to be ready to flee when necessity should compel. A faint hope that she might meet her lover doubtless was the secret of her tarrying. At last her brother sent a peremptory order for her to join him, and she promised to go down in a large, bateau(1) which was expected to leave with several families on the following day.

Early

the next morning a black (July 27, 1777.) servant boy belonging to Mrs.

M'Neil espied some Indians stealthily approachingt the house, and, giving

the alarm to the inmates, he fled to the fort, about eighty rods distant.

Mrs. M'Neil's daughter, the young friend of Jenny, and mother of my informant,

was with some friends in Argyle, and the family consisted of only the widow

and Jenny, two small children, and a black female servant. As usual at that

time, the kitchen stood a few feet from the house; and when the alarm was

given the black woman snatched up the children and fled to the kitchen,

and retreated through a trap-door to the cellar.(2) Mrs. M'Neil and Jenny

followed, but the former being aged and very corpulent, and the latter young

and agile, Jenny' reached the trap-door first. Before Mrs. M'Neil could

fully descend, the Indians were in the house, and a powerful savage seized

her by the hair and dragged her up. Another went into the cellar and brought

out Jenny, but the black face of the negro woman wall not seen in the dark,

and she and the children remained unharmed.

Early

the next morning a black (July 27, 1777.) servant boy belonging to Mrs.

M'Neil espied some Indians stealthily approachingt the house, and, giving

the alarm to the inmates, he fled to the fort, about eighty rods distant.

Mrs. M'Neil's daughter, the young friend of Jenny, and mother of my informant,

was with some friends in Argyle, and the family consisted of only the widow

and Jenny, two small children, and a black female servant. As usual at that

time, the kitchen stood a few feet from the house; and when the alarm was

given the black woman snatched up the children and fled to the kitchen,

and retreated through a trap-door to the cellar.(2) Mrs. M'Neil and Jenny

followed, but the former being aged and very corpulent, and the latter young

and agile, Jenny' reached the trap-door first. Before Mrs. M'Neil could

fully descend, the Indians were in the house, and a powerful savage seized

her by the hair and dragged her up. Another went into the cellar and brought

out Jenny, but the black face of the negro woman wall not seen in the dark,

and she and the children remained unharmed.

With the two women the savages started off, on the road toward Sandy Hill, for Burgoyne's camp; and when they came to the foot of the ascent on which the pine tree stands, where the road forked, they caught two horses that were grazing, and attempted to place their prisoners upon them. Mrs. M'Neil was too heavy to be lifted on the horse easily, and as she signified by signs that she could not ride, two stout Indians took her by the arms and hurried her up the road over the hill, while the others, with Jenny on the horse, went along the road running west of the tree.

The negro boy who ran to the fort gave the alarm, and a small detachment was imme-

1 Bateaux were rudely constructed of logs and planks, broad

and without a keel. They had small draught and would carry large loads in

quite shallow water. In still water and against currents they were propelled

by long driving-poles. The ferry-scows or flats on the southern, and western

rivers are very much like the old bateaux. They were sometimes furnished

with a mast for lakes and other deep water, and had cabins erected on them.

2 Traces of this cellar and of the foundation of the house are still visible

in the garden of Dr. Norton. in Fort Edward village, who is a relative of

the family by marriage.

99

diately sent out to effect a rescue. They fired several volleys at the Indians, but the savages escaped unharmed. Mrs. M'Neil said that the Indians, who were hurrying her up the hill, seemed to watch the flash of the guns, and several times they threw her upon her face at the same time falling down themselves, and she distinctly heard the balls whistle above them. When they got above the second hill from the village the firing ceased; they then stopped, stripped her of all her garments except her chemise, and in that plight led her into the British camp. There she met her kinsman, General Fraser, and reproached him bitterly for sending his "scoundrel Indians" after her. He denied all knowledge of her being away from the city of New York, and took every pains to make her comfortable. She was so large that not a woman in camp had a gown big enough for her, so Fraser lent her his camp coat for a garment, and a pocket-handkerchief as a substitute for her stolen cap.

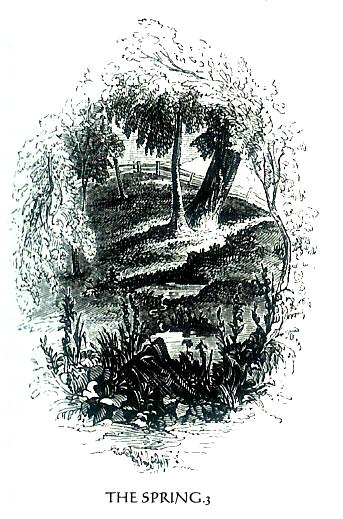

Very soon after Mrs. M'Neil was taken into the British camp, two parties

of Indians arrived with  scalps.

She at once recognised the long glossy hair of Jenny, (1) and, though shuddering

with horror, boldly charged the savages with her murder, which they stoutly

denied. They averred that, while hurrying her along the road on horseback,

near the spring west of the pine tree, a bullet from one of the American

guns, intended for them, mortally wounded the poor girl, and she fell from

the horse. Sure of losing a prisoner by death, they took her scalp as the

next best thing for them to do, and that they bore in triumph to the camp,

to obtain the promised reward for such trophies. Mrs. M'Neil always believed

the story of the Indians to be true, for she knew that they were fired upon

by the detachment from the fort, and it was far more to their interest to

carry a prisoner than a scalp to the British commander, the price for the

former being much greater. In fact, the Indians were so restricted by Burgoyne's

humane instructions respecting the taking of scalps, that their chief solicitude

was to bring a prisoner alive and unharmed into the camp.(2) And the probability

that Miss M'Crea was killed as they alleged is strengthened by the fact

that they took the corpulent Mrs. M'Neil, with much fatigue and difficulty,

uninjured to the British lines, while Miss M'Crea, quite light and already

on horseback, might have been carried off with far greater ease.

scalps.

She at once recognised the long glossy hair of Jenny, (1) and, though shuddering

with horror, boldly charged the savages with her murder, which they stoutly

denied. They averred that, while hurrying her along the road on horseback,

near the spring west of the pine tree, a bullet from one of the American

guns, intended for them, mortally wounded the poor girl, and she fell from

the horse. Sure of losing a prisoner by death, they took her scalp as the

next best thing for them to do, and that they bore in triumph to the camp,

to obtain the promised reward for such trophies. Mrs. M'Neil always believed

the story of the Indians to be true, for she knew that they were fired upon

by the detachment from the fort, and it was far more to their interest to

carry a prisoner than a scalp to the British commander, the price for the

former being much greater. In fact, the Indians were so restricted by Burgoyne's

humane instructions respecting the taking of scalps, that their chief solicitude

was to bring a prisoner alive and unharmed into the camp.(2) And the probability

that Miss M'Crea was killed as they alleged is strengthened by the fact

that they took the corpulent Mrs. M'Neil, with much fatigue and difficulty,

uninjured to the British lines, while Miss M'Crea, quite light and already

on horseback, might have been carried off with far greater ease.

It was known in camp that Lieutenant Jones was betrothed to Jenny, and the story got abroad that he had sent the Indians for her, that they quarreled on the way respecting the reward he had offered, and murdered her to settle the dispute. Receiving high touches of coloring as it went from one narrator to another, the sad story became a tale of darkest horror, and produced a deep and wide-spread indignation. This was heightened by (September 2, 1777.) a published letter from Gates to Burgoyne, charging him with allowing the Indians

1 It was of extraordinary length and beauty, measuring a

yard and a quarter. She was then about twenty years old, and a very lovely

girl; not lovely in beauty of face, according to the common standard of

beauty, but so lovely in disposition, so graceful in manners, and so intelligent

in features, that she was a favorite of all who knew her.

2 "I positively forbid bloodshed when you are not opposed in arms.

Aged men, women, children, and prisoners must be held sacred from the knife

and hatchet, even in the time of actual conflict. You shall receive compensation

for the prisoners you take, but you shall be called to account for scalps.

In conformity and indulgence of your customs, which have affixed an idea

of honor to such badges of victory, you shall be allowed to take the scalps

of the dead when killed by your fire and in fair opposition; but on no account,

or pretense, or subtilty, or prevarication are they to be taken from the

wounded, or even the dying; and still less pardonable, if possible, will

it be held to kill men in that condition on purpose, and upon a supposition

that this protection to the wounded would be thereby evaded."-Extract

from the Speech of Burgoyne to the Indians assembled upon the Bouquet River,

June 21, 1777.

3 This is a view of a living spring, a few feet below the noted pine tree,

the lower portion of whIch is seen near the top of the engraving. The spring

is beside the old road, traces of which may be seen.

100

to butcher with impunity defenseless women and children. " Upward of one hundred men, women, and children," said Gates, "have perished by the hands of the ruffians, to whom, it is asserted, you have paid the price of blood." Burgoyne flatly denied this assertion, and declared that the case of Jane M'Crea was the only act of Indian cruelty of which he was informed. His information must have been exceedingly limited, for on the same day when Jenny lost her life a party of savages murdered the whole family of John Allen, of Argyle, consisting of himself, his wife, three children, a sister-in-law, and three negroes. The daughter of Mrs. M'Neil, already mentioned, was then at the house of Mr. Allen's father-in-law, Mr. Gilmer, who, as well as Mr. Allen, was a Tory. Both were afraid of the savages, nevertheless, and were preparing to flee to Albany. On the morning of the massacre a younger daughter of Mr. Gilmer went to assist Mrs. Allen in preparing to move. Not returning when expected, her father sent a negro boy down for her. He soon returned, screaming, "They are all dead-father, mother, young missus, and all!" It was too true. That morning, while the family were at breakfast, the Indians burst in upon them and slaughtered every one. Mr. Gilmer and his family left in great haste for Fort Edward, but proceeded very cautiously for fear of the savages. When near the fort, and creeping warily along a ravine, they discovered a portion of the very party who had plundered Mrs. McNeil's house in the morning. They had emptied the straw from the beds and filled the ticks with stolen articles. Mrs. M'Neil's daughter, who accompanied the fugitive family, saw her mother's looking-glass tied upon the back of one of the savages. They succeeded in reaching the fort in safety.

Burgoyne must soon have forgotten this event and the alarm among the loyalists because of the murder of a Tory and his family; forgotten how they flocked to his camp for protection, and Fraser's remark to the frightened loyalists, "It is a conquered country, and we must wink at these things;" and how his own positive orders to the Indians, not to molest those having protection, caused many of them to leave him and return to their hunting grounds on the St. Lawrence. It was all dark and dreadful, and Burgoyne was willing to retreat behind a false assertion, to escape the perils which were sure to grow out of an ad. mission of half the truth of Gates's letter. That letter, as Sparks justly remarks, was more ornate than forcible, and abounded more in bad taste than simplicity and pathos; yet it was suited to the feelings of the moment, and produced a lively impression in every part of America. Burke, in the exercise of all his glowing eloquence, used the story with powerful effect in the British House of Commons, and made the dreadful tale familiar throughout Europe.

Burgoyne, who was at Fort Ann, instituted an inquiry into the matter. He summoned the Indians to council, and demanded the surrender of the man who bore off the scalp, to be punished as a murderer. Lieutenant Jones denied all knowledge of the matter, and utterly disclaimed any such participation as the sending of a letter to Jenny, or of an Indian escort to bring her to camp. He had no motive for so doing, for the American army was then retreating; a small guard only was at Fort Edward, and in a day or two the British would have full possession of that fort, when he could have a personal interview with her. Burgoyne, instigated by motives of policy rather than by judgment and inclination, pardoned the savage who scalped poor Jenny, fearing that a total defection of the Indians would be the result of his punishment.(1)

Lieutenant Jones, chilled with horror and broken in spirit by the event, tendered a resignation of his commission, but it was refused. He purchased the scalp of his Jenny, and with this cherished memento deserted, with his brother, before the army reached Saratoga, and retired to Canada. Various accounts have been given respecting the subsequent fate of Lieutenant Jones. Some assert that, perfectly desperate and careless of life, he rushed into the thickest of the battle on Bemis's Heights, and was slain; while others allege that he died within three years afterward, heart-broken and insane. But neither assertion is true. While searching for Mrs. F-n among her friends at Glenn's Falls, I called at the

1 Earl of Harrington's Evidence in Burgoyne's "State of the Expedition," p. 66.

101

house of Judge R-s, whose lady is related by marriage to the family of Jones. Her aunt married a brother of Lieutenant Jones, and she often heard this lady speak of him. He lived in Canada to be an old man, and died but a few years ago. The death of Jenny was a heavy blow, and he never recovered from it. In youth he was gay and exceedingly garrulous, but after that terrible event he was melancholy and taciturn. He never married, and avoided society as much as business would permit. Toward the close of July in every year, when the anniversary of the tragedy approached, he would shut himself in his room and refuse the sight of anyone; and at all times his friends avoided any reference to the Revolution in his presence.

At the time of this tragical event the American army under General Schuyler was encamped at Moses's Creek, five miles below Fort Edward. One of its two divisions was placed under the command of Arnold, who had just reached the army. His division (July 23, 1777.) included the rear-guard left at the fort. A picket-guard of one hundred men, under Lieutenant VanVechten, was stationed on the hill a little north of the pine tree; and at the moment when the house of Mrs. M'Neil was attacked and plundered, and herself and Jenny were carried off, other parties of Indians, belonging to the same expedition, came rushing through the woods from different points, and fell upon the Americans. Lieutenant VanVechten and several others were killed and their scalps borne off. Their bodies, with that of Jenny, were found by the party that went out from the fort in pursuit. She and the officer were lying near together, close by the spring already mentioned, and only a few feet from the pine tree. They were stripped of clothing, for plunder was the chief incentive of the savages to war. They were borne immediately to the fort, which the Americans at once evacuated, and Jane did indeed go down the river in the bateau in which. she had intended to embark, but not glowing with life and beauty, as was expected by her fond brother. With the deepest grief, he took charge of her mutilated corpse, which was buried at the same time and place with that of the lieutenant, on the west bank of the Hudson, near the mouth of a small creek about three miles below Fort Edward.

Mrs. M'Neil lived many years, and was buried in the small village cemetery, very near the ruins of the fort. In the summer of 1826 the remains of Jenny were taken up and deposited in the same grave with her. They were followed by a long train of young men and maidens, and the funeral ceremonies were conducted by the eloquent but unfortunate Hooper Cummings, of Albany, at that time a brilliant light in the American pulpit, but destined, like a glowing meteor, to go suddenly down into darkness and gloom. Many who were then young have a vivid recollection of the pathetic discourse of that gifted man, who on that occasion "made all Fort Edward weep," as he delineated anew the sorrowful picture of the immolation of youth and innocence upon the horrid altar of war.

A plain white marble slab, about three feet high, with the simple inscription Jane M'Crea, marks the spot of her interment. Near by, as seen in the picture, is an antique brown stone slab, erected to the memory of Duncan Campbell, a relative of Mrs. M'Neil's first husband, who was mortally wounded at Ticonderoga in 1758.(1) Several others of the same name lie near, members of the family of Donald Campbell, a brave Scotchman who was with Montgomery at the storming of Quebec in 1775.

We lingered long in the cool shade at the spring before departing for the village burial ground where the remains of Jenny rest. As we emerged from the woods we saw two or

1 The following is the inscription:

HERE LYES THE BODY OF DUNCAN CAMPBELL, OF INVERSAW. ESQR., MAJOR TO THE

OLD HIGHLANDS REGT., AGED 55 YEARS, WHO DIED THE 17TH JULY, 1758, OF THE

WOUNDS HE RECEIVED IN THE ATTACK OF THE RETRENCHMENTS OF TICONDEROGA OR

CARILLON THE 8TH JULY, 1758.

102

three persons with a horse and wagon, slowly ascending the hill from the village. In the wagon, upon a mattress, was a young girl who had been struck by lightning, two days before, while drawing water from a well.(1) Although alive, her senses were all paralyzed by the shock, and her sorrowing father was carrying her home, perhaps to die. With brief words of consoling hope, we stepped up and looked upon the stricken one. Her breathing was soft and slow-a hectic glow was upon each cheek; but all else of her fair young face was pale as alabaster except her lips. It was grievous, even to a stranger, to look upon a young life so suddenly prostrated, and we turned sadly away to go to the grave of another, who in the bloom of young womanhood was also smitten to the earth, not by the lightning from Heaven, but by the arm of warring man.

The village burial-ground is near the site of the fort, and was thickly strewn with wild flowers. We gathered a bouquet from the grave of Jenny, and preserved it for the eye of the curious in an impromptu herbarium made of a city newspaper. A few feet from her "narrow house" is the grave of Colonel Robert Cochran, whom I have already mentioned as commanding a detachment of militia at Fort Edward at the time of Burgoyne's surrender. He was a brave officer, and was warmly attached to the American cause. In 1778 he was sent to Canada as a spy. His errand being suspected, a large bounty was offered for his head. He was obliged to conceal himself, and while doing so at one time in a brush-heap, he was taken dangerously ill. Hunger and disease made him venture to a log cabin in sight. As he approached he heard three men and a woman conversing on the subject of the reward for his head, and discovered that they were actually forming plans for his capture. The men soon left the cabin in pursuit of him, and he immediately crept into the presence of the woman, who was the wife of one of the men, frankly told her his name, and asked her protection. That she kindly promised him, and gave him some nourishing food and a bed to rest upon. The men returned in the course of a few hours, and she concealed Cochran in a cupboard, where he overheard expressions of their confident anticipations that before another sun they would have the rebel spy, and claim the reward. They refreshed themselves, and set off again in search of him. The kind woman directed him to a place of concealment, some distance from her cabin, where she fed and nourished him until he was able to travel, and then he escaped beyond the British lines. Several years afterward, when the war had closed, the colonel lived at Ticonderoga, and there he accidentally met his deliverer, and rewarded her handsomely for her generous fidelity in the cause of suffering humanity. Colonel Cochran died in 1812, at Sandy Hill, and was buried at Fort Edward. It was hot noon when I left the village cemetery, and took shelter under the shadow of the venerable balm of Gilead tree at the place of the water-gate of the fort. A few rods below is the mouth of Fort Edward Creek, on the south of which the British army were encamped when Burgoyne tarried there to send an expedition to Bennington, and, after that disastrous affair, to recruit and discipline his forces. Dividing the waters of the Hudson in front of the fort is Rogers's Island, a beautiful and romantic spot, which was used as a camp-ground by the English and French alternately during the French and Indian war. Almost every year the

1 This mournful event occurred in the village, very near

the same spot where, a year before, five men in a store were instantly killed

by one thunder-bolt.

2 This sketch is taken from within the intrenchments of Fort Edward, near

the magazine, looking southwest. On the left, just beyond the balm of Gilead

tree, is seen the creek, and on the right, across the water, Rogers's Island.

103

plow turns up some curious relics of the past upon the island, such as bayonets, tomahawks, buttons, bullets, cannon-balls, coin, arrow-heads, &c. Dr. Norton, of Fort Edward, gave me a skull that had been exhumed there, which is remarkable for its excessive thickness; not so thick, however, as to resist the force of a musket-ball which penetrated it, and doubtless deprived its owner of life. It is three eighths of an inch thick where the bullet entered in front, and, notwithstanding its long inhumation, the sutures are perfect. Its form is that of the negro, and it probably belonged to the servant of some officer stationed there.

The silver coin found in the vicinity of Fort Edward is called by the people "cob money." The derivation of this name I could not learn. I obtained two pieces of it, both of which are Spanish coin. The larger one is a cross-pistareen, of the value of sixteen cents; the other is a quarter fraction of the same coin. They are very irregular in form, and the devices and dates are quite imperfect. The two in my possession are dated respectively 1741, 1743. These Spanish small coins composed the bulk of specie circulation among the French in Canada at that time.