WE dined at three, and immediately left the pleasant little village of Fort Edward in a barouche for Glenn's Falls, by the way of Sandy Hill, a distance of six miles. The latter village is beautifully situated upon the high left bank of the Hudson, where the river makes a sudden sweep from an easterly to a southerly course. Here is the termination of the Hudson Valley, and above it the river courses its way in a narrow channel, among rugged rocks and high, wooden bluffs, through as wild and romantic a region as the most enthusiastic traveler could desire.

It was early in the afternoon when we reached the Mansion House at Glenn's Falls, near the cataract. All was bustle and confusion, for here is the brief tarrying-place of fashionable tourists on their way from Saratoga Springs to Lake George. There was a constant arrival and departure of visitors. Few remained longer than to dine or sup, view the falls at a glance, and then hasten away to the grand summer lounge at Caldwell, to hunt, fish, eat, drink, dance, and sleep to their heart's content. We were thoroughly wearied by the day's ramble and ride, but time was too precious to allow a moment of pleasant weather to pass by unimproved. Comforted by the anticipation of a Sabbath test the next day, we brushed the dust from our clothes, made a hasty toilet, and started out to view the falls, and search for the tarrying-place of Mrs. F-n, of Fort Edward.

Here the whole aspect of things is changed. Hitherto our journey had been among the quiet and beautiful; now every thing in nature was turbulent and grand. The placid river was here a foaming cataract, and gentle slopes, yellow with the ripe harvest, were exchanged for high, broken hills, some rocky and bare, others green with the oak and pine or dark with the cedar and spruce. Here nature, history, and romance combine to interest and please, and geology spreads out one of its most wonderful pages for the scrutiny of the student and philosopher. All over those rugged hills Indian warriors and hunters scouted for ages before the pale face made his advent among them; and the slumbering echoes were often awakened in the last century by the crack of musketry and the roar of cannon, mingled with the loud war-hoop of the Huron, the Iroquois, the Algonquin, the Mohegan, the Delaware, the Adirondack, and the Mohawk, when the French and English battled for mastery in the vast forests that skirted the lakes and the St. Lawrence. Here, amid the roar of this very cataract, if romance may be believed, the voice of Uncas, the last of the Mohegans, was heard and heeded; here Hawk Eye kept his vigils; here David breathed his nasal melody; and here Duncan Heyward, with his lovely and precious wards, Alice and Cora Monroe, fell into the hands of the dark and bitter Mingo chief. 1

1 See Cooper's" Last of the Mohicans."

105

The natural scenery about the falls is very picturesque, but the accompaniments of puny art are exceedingly incongruous, sinking the grand and beautiful into mere burlesque. How expertly the genius of man, quickened by acquisitiveness, fuses the beautiful and useful in the crucible of gain, and, by the subtle alchemy of profit, transmutes the glorious cascade and its fringes of rock and shrub into broad arable acres, or lofty houses, or speeding ships, simply by catching the bright stream in the toils of a mill-wheel. Such meshes are here spread out on every side to ensnare the leaping Hudson, and the rickety buildings, the clatter of machinery, and the harsh grating of saws, slabbing the huge black marble rocks of the shores into city mantels, make horrid dissonance of that harmony which the eye and ear expect and covet where nature is thus beautiful and musical.

A bridge,

nearly six hundred feet long, and resting in the center upon a marble island,

spans the river at the foot of the falls, and from its center there is a

fine view of the cataract. The entire descent of the river is about sixty

feet. The undivided stream first pours over a precipice nine hundred feet

long, and is then separated into three channels by rocks piled in confusion,

and carved. and furrowed, and welled, and polished by the rushing waters.

Below, the channels unite, and in one deep stream the waters flow on gently

between the quarried cliffs of fine black marble, which rise in some places

from thirty to seventy feet in height, and are beautifully stratified. Many

fossils are imbedded in the rocks, among which the trilobite is quite plentiful.

Here the heads (so exceedingly rare) are frequently found.

A bridge,

nearly six hundred feet long, and resting in the center upon a marble island,

spans the river at the foot of the falls, and from its center there is a

fine view of the cataract. The entire descent of the river is about sixty

feet. The undivided stream first pours over a precipice nine hundred feet

long, and is then separated into three channels by rocks piled in confusion,

and carved. and furrowed, and welled, and polished by the rushing waters.

Below, the channels unite, and in one deep stream the waters flow on gently

between the quarried cliffs of fine black marble, which rise in some places

from thirty to seventy feet in height, and are beautifully stratified. Many

fossils are imbedded in the rocks, among which the trilobite is quite plentiful.

Here the heads (so exceedingly rare) are frequently found.

By the contribution of a York shilling to an intelligent lad who kept"

watch and ward" at a flight of steps below the bridge, we procured

his permission to descend to the rocks below, and his services as guide

to the" Big Snake" and the" Indian Cave." The former

is a petrifaction on the surface of a flat rock, having the appearance of

a huge serpent; the latter extends through the small

Island from one channel to the other, and is pointed out as the place where

Cooper's sweet young heroines, Cora and Alice, with Major Heyward and the

singing-master, were concealed. The melody of a female voice, chanting an

air in a minor key, came up from the cavern, and we expected every moment

to hear the pitch-pipe of David and the "Isle of Wright." The

spell was soon broken by a merry laugh, and three young girls, one with

a torn barege, came clambering up from the narrow entrance over which Uncas

and Hawk Eye cast the green branches to conceal the fugitives. In time of

floods this cave is filled, and all the dividing rocks below the main fall

are covered with water, presenting one vast foaming sheet. A long drought

had greatly diminished the volume of the stream when we were there, and

materially lessened the usual grandeur of the picture.

We passed the Sabbath at the falls. On Monday morning I arose at four, and went down to the bridge to sketch the cascade. The whole heavens were overcast, and a fresh breeze from the southeast was driving portentous scuds before it, and piling them in dark masses along the western horizon. Rain soon began to fall, and I was obliged to retreat under the bridge, and content myself with sketching the more quiet scene of the river and shore below the cataract.

We left Glenn's Falls in a "Rockaway" for Caldwell, on Lake George, nine miles northward, at nine in the morning, the rain falling copiously. The road passes over a wild,

1 This view was taken from under the bridge, looking down the river. river just below where the figures stand. The noted cave opens upon the river just below where the figure stand.

106

broken, and romantic region. Our driver was a perfect Jehu. The plank road (since finished) was laid a small part of the way, and the speed he accomplished thereon he tried to keep up over the stony ground of the old track, to "prevent jolting .'"

On

the right side of the road, within four miles of Lake George, is a huge

boulder called "Williams's Rock." It was so named from the fact

that near it Colonel Ephraim Williams was killed on the 8th of September,

1755, in an engagement with the French and Indians under Baron Dieskau.

Major-general (afterward Sir William) Johnson was at that time at the head

of lake George, with a body of provincial troops, and a large party of Indians

under hendrick, the famous Mohawk sachem. Dieskau, who was at Skenesborough,

marched along the course of Wood Creek to attack Fort Edward, but the Canadians

and Indians were so afraid of cannon that, when within two miles of the

fort, they urged him to change his course and attack Johnson in his camp

on Lake George. To this request he acceded, for he ascertained by his scouts

that Johnson was rather carelessly encamped, and was probably unsuspicious

of danger, Information of his march was communicated to the English commander

at midnight, September 7th, 1755 and early in the morning a council of war

was held. It was determined to send out a small party to meet the French,

and the opinion of Hendrick was asked. He shrewdly said, "If they are

to fight, they are too few; if they are to be killed, they are too many."

His objection to the proposition to separate them into three divisions was

quite as sensibly and laconically expressed. Taking three sticks and putting

them together, he remarked, "Put them together, and you can't break

them. Take them one by one, and you can break them easily." Johnson

was guided by the opinion of Hendrick, and a detachment of twelve hundred

men in one body, under Colonel Williams, was sent out to meet the approaching

enemy.

Before commencing their march, Hendrick mounted a gun-carriage and harangued his warriors in a strain of eloquence which had a powerful effect upon them. He was then about sixty-five yean old. His head was covered with long white locks, and every warrior loved him with the deepest veneration.. President Dwight, referring to this speech, says, "Lieutenant-colonel

1 This view is taken from the road, looking northward. In

the distance is seen the highest point of the French Mountain, on the left

of which is Lake George. From this commanding height the French scout had

a fine view of all the English movements at the head of the lake.

2 The portrait here given of the chief is from a colored print published

in London during the lifetime of the sachem. It was taken while he was in

England, and habited in the full court dress presented to him by the king.

Beneath the picture is engraved, "The brave old Hendrick, the great

sachem or chief of the Mohawk Indians, one of the six nations now in alliance

with, and subject to, the King of Great Britain."

3 Hendrick (sometimes called King Hendrick) was born about 1680, and generally

lived at the Upper Castle, upon the Mohawk. He stood high in the estimation

of Sir William Johnson, and was one of the most active and sagacious sachems

of his time. When the tidings of his death were communicated to his son,

the young chief gave the usual groan upon such occasions, and, placing his

hand over his heart exclaimed, "My father still alive here. The son

is now the father, and stands here ready to fight."-Gentlemen's

Magazine.

Sir William Johnson obtained from Hendrick nearly one hundred thousand acres

of choice land, now lying chiefly in Herkimer county, north of the Mohawk,

in the following manner: The sachem, being al the baronet's house, saw a

richly-embroidered coat and coveted it. The next morning he said to Sir

William, "Brother, me dream last night." "Indeed," answered

Sir William, "what did my red brother

107

Pomeroy, who was present and heard this effusion of Indian eloquence, told me that, although he did not understand a word of the language, such were the animation of Hendrick. the fire of his eye, the force of his gestures, the strength of his emphasis, the apparent propriety of the inflections of his voice, and the natural appearance of his whole manner, that himself was more deeply affected with this speech than with any other he had ever heard."

The French, advised by scouts of the march of the English, approached with their line in the form of a half moon, the road cutting the center. The country was so thickly wooded that all correct observation was precluded, and at Rocky Brook, four miles from Lake George, Colonel Williams and his detachment found themselves directly in the hollow of the half moon. A heavy fire was opened upon them in front and on both flanks at the same moment, and the slaughter was dreadful. Colonel Williams was shot dead near the rock before mentioned, and Hendrick fell, mortally wounded by a musket-ball in the back. This circumstance gave him great uneasiness, for it seemed to imply that he had turned his back upon his enemy. The fatal bullet carne from one of the extreme flanks. On the fall of Williams, Lieutenant-colonel Whiting succeeded to the command, and effccted a retreat so judiciously that he saved nearly all of the detachment who were not killed or wounded by the first onslaught.(1)

So

careless and apathetic was General Johnson, that he did not commence throwing

up breast-works at his camp until after Colonel Williams had marched, and

Dieskau was on the road to meet him. The firing was heard at Lake George,

and then the alarmed commander began in earnest to raise defenses, by forming

a breast-work of trees, and mounting two cannon which he had fortunately

received from Fort Edward the day before, when his men thus employed should

have been sent out to re-enforce the retreating regiment. Three hundred

were, indeed, sent out, but were totally inadequate. They met the flying

English, and, joining in the retreat, hastened back to the camp, closely

pursued by the French.

A short distance from Williams's Rock is a small, slimy, bowl-shaped pond, about three hundred feet in diameter, and thickly covered with the leaves of the water-lily. It is near the battle-ground where Williams and his men were slain, and the French made it the sepulcher for the slaughtered Englishmen. Tradition avers that for many years its waters bore a bloody hue,

dream?" "Me dream that coat be mine." "It

is yours," said the shrewd baronet. Not long afterward Sir William

visited the sachem, and he too had a dream. " Brother," he said,

"I dreamed last night." "What did my pale-faced brother dream?"

asked Hendrick. "I dreamed that this tract of land was mine,"

describing a square bounded on the south by the Mohawk, on the east by Canada

Creek, and north and west by objects equally well known. Hendrick was astonished.

He saw the enormity of the request, but was not to be outdone in generosity.

He sat thoughtfully for a moment, and then said, "Brother, the land

is yours, but you must not dream again." The title was confirmed by

the British government, and the tract was called the Royal Grant.-Simms's

Schoharie County, p. 124.

1 Colonel Ephraim Williams was born in 1715, at Newton, Massachusetts. He

made several voyages to Europe in early life. Being settled at Stockbridge

when the war with France, in 174O, commenced, and possessed of great military

talent, he was intrusted with the command of the line of Massachusetts torts

on the west side of the Connecticut River. He joined General Johnson, at

the head of a regiment, in 1755, and, as we have seen, fell while gallantly

leading his men against the enemy. By his will, made before joining Johnson,

he bequeathed his property to a township west of Fort Massachusetts, on

the condition that it should be called Williamstown, and the money used

for the establishment and maintenance of a free school. The terms were complied

with, and the school was afterward incorporated (1793) as a college. Such

was the origin of Williams's College. Colonel Williams was forty years old

at the time of his death.

108

and it has ever since been called Bloody Pond. I alighted in the rain, and' made my way through tall wet grass and tangled vines, over a newly-cleared field, until I got a favorable view for the sketch here presented, which I hope the reader will highly prize; for it cost a pair of boots, a linen" sack" ruined by the dark droppings from a cotton umbrella, and a box of cough lozenges.

It was almost noon when we reined up at the Lake House at Caldwell. We had anticipated much pleasure from the first sight of Horicon, but a mist covered its waters, and its mountain framework was enveloped in fog; so we reserved our sentiment for use the next fair day, donned dry clothing, and sat quietly down in the parlor to await the sovereign pleasure of the storm.

Lake George is indeed a beautiful sheet of water, and along its whole length of thirty-six miles almost every island, bay, and bluff is clustered with historic associations. On account of the purity of its waters, the Indians gave it the name of Horican, or Silver Water. They also called it Canideri-oit, or The Tail of the Lake, on account of it; connection with Lake Champlain.(1) It was visited by Samuel Champlain in 1609, and some suppose that he gave his name to this lake instead of the one which now bears it. It is fair to infer, from his own account, that he penetrated southward as far as Glenn's Falls; and it is not a little remarkable that in the same year, and possibly at the same season, Hendrick Hudson was exploring below the very stream near the head-waters of which the French navigator was resting. Strange that two adventurers, in the service of different sovereigns ruling three thousand miles away, and approaching from different points of the compass, so nearly met in the vast forests of wild America. The French, who afterward settled at Chimney Point, on Lake Champlain, frequently visited this lake, and gave it the name of Sacrament, its pure waters suggesting the idea.(2)

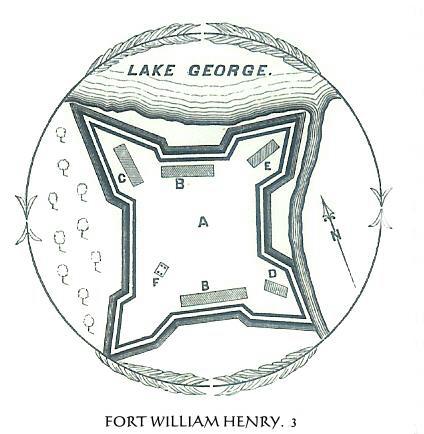

The

little village of Caldwell contains about two hundred inhabitants, and is

situated near the site of Fort William Henry, at the head of the lake, a

fortress erected by General Johnson toward the close of 1755, after his

battle there with the French under Dieskau. That battle occurred on the

same day when Colonel Williams and his detachment were routed at Rocky Brook.

The French pursued the retreating English vigorously, and about noon they

were seen approaching in considerable force and regular order, aiming directly

toward the center of the British encampment. When within one hundred rods

of the breast-works, in the open valley in front of the elevation on which

Fort George (now a picturesque ruin) Was afterward built, Dieskau halted

and disposed his Indians and Canadians upon the right and left flanks. The

regular troops, under the immediate command of the baron, attacked the English

center, but, having only small arms, the effect was trifling. The English

reserved their fire until the Indians and Canadians were close upon them,

when with sure aim they poured upon them a volley of musket-balls which

mowed them down like grass before the

The

little village of Caldwell contains about two hundred inhabitants, and is

situated near the site of Fort William Henry, at the head of the lake, a

fortress erected by General Johnson toward the close of 1755, after his

battle there with the French under Dieskau. That battle occurred on the

same day when Colonel Williams and his detachment were routed at Rocky Brook.

The French pursued the retreating English vigorously, and about noon they

were seen approaching in considerable force and regular order, aiming directly

toward the center of the British encampment. When within one hundred rods

of the breast-works, in the open valley in front of the elevation on which

Fort George (now a picturesque ruin) Was afterward built, Dieskau halted

and disposed his Indians and Canadians upon the right and left flanks. The

regular troops, under the immediate command of the baron, attacked the English

center, but, having only small arms, the effect was trifling. The English

reserved their fire until the Indians and Canadians were close upon them,

when with sure aim they poured upon them a volley of musket-balls which

mowed them down like grass before the

1 Spafford's Gazetteer of New York.

2 The bed of the lake is a yellowish sand, and the water is so transparent

that a white object, such as an earthen plate, may be seen upon the bottom

at a depth of nearly forty feet. The delicious salmon trout, that weigh

from five to twenty pounds, silver trout, pike, pickerel, and perch are

found here in great abundance, and afford fine sport and dainty food for

the swarms of visitors at the Lake House during the summer season.

3 The extent of the embankments and fosse of this fort was fourteen hundred

feet, and the barracks were built of wood upon a strong foundation of lime-stone,

which abounds in the neighborhood. This plan is copied from a curious old

picture by Blodget, called a "Prospective Plan of the Battles near

Lake George 1755."

109

scythe. At the same moment a bomb-shell was thrown among them by a howitzer, while two field pieces showered upon them a quantity of grape-shot. The savage allies, and almost as savage colonists, greatly terrified, broke and fled to the swamps in the neighborhood. The regulars maintained their ground for some time, but, abandoned by their companions, and terribly galled by the steady fire from the breast-works, at length gave way, and Dieskau attempted a retreat. Observing this, the English leaped over their breast-works and pursued them. The French were dispersed in all directions, and Dieskau, wounded and helpless, was found leaning upon the stump of a tree. As the provincial soldier(1) who discovered him approached, he put his hand in his pocket to draw out his watch as a bribe to allow him to escape. Supposing that he was feeling for a pocket pistol, the soldier gave him a severe wound in the hip with a musket-ball. He was carried into the English camp in a blanket and tenderly treated, and was soon afterward taken to Albany, then to New York, and finally to England, where he died from the effects of his wounds. Johnson was wounded at the commencement of the conflict in the fleshy part of his thigh, in which a musket-ball lodged, and the whole battle was directed for five consecutive hours by General Lyman, the second in command.(2)

Johnson's Indians, burning with a fierce desire to avenge the death of Hendrick, were eager to follow the retreating enemy; and General Lyman proposed a vigorous continuation of efforts by attacking the French posts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point, on Lake Champlain. But Johnson, either through fear, a love of ease, or some other inexplicable cause, withheld his consent, and the residue of the autumn was spent in erecting Fort William Henry.

In the colonial wars, as well as in the war of our Revolution, the British government was often unfortunate in its choice of commanders. Total inaction, or, at best, great tardiness, frequently marked their administration of military affairs. They could not comprehend the elastic activity of the provincials, and were too proud to listen to their counsels. This tardiness and pride cost them many misfortunes, either by absolute defeat in battle, or the theft of glorious opportunities for victory through procrastination. Their shrewd savage allies saw and lamented this, and before the commissioners of the several colonies, who met at Albany in 1754 to consult upon a plan of colonial alliance, in which the SIX NATIONS(3) were invited to join, Hendrick administered a pointed rebuKe to the governor and military commanders. The sachems were first addressed by James Delaney, then lieutenant-governor of New York; and Hendrick, who was a principal speaker, in the course of a reply remarked, "Brethren, we have not as yet confirmed the peace with them (meaning the French-Indian allies). 'Tis your fault, brethren; we are not strengthened by conquest, for we should have gone and taken Crown Point, but you hindered us. We had concluded to go and take it, but were told it was too late, that the ice would not bear us. Instead of this, you burned your own fort at Sar-ragh-to-gee [near old Fort Hardy], and ran away from it, which was a shame and a scandal to you. Look about your country, and see; you have no fortifications about you-no, not even to this city. 'Tis but one step from Canada hither, and the French may easily come and turn you out of doors.

"Brethren, you were desirous we should open our minds and our hearts to you: look at

1 This soldier is believed to have been General Seth Pomeroy,

of Northampton, Massachusetts.-Everett's Life of Stark.

2 At this battle General Stark, the hero of Bennington, then a lieutenant

in the corps of Rogers's Rangers, was first initiated in the perils and

excitements of regular warfare.

3 The SIX NATIONS consisted of the tribes of the Mohawks, Onondagas, Oneidas,

Senecas, Cayugas, and Tuscaroras. The first five were a long time allied,

and known as the Five Nations. They were joined by the Tuscaroras of North

Carolina in 1714, and from that time the confederation was known by the

title of the Six Nations. Their great council fire was in the special keeping

of the Onondagas, by whom it was always kept burning. This confederacy was

a terror to the other Indian tribes, and extended its conquests even as

far as South Carolina, where it waged war against, and nearly exterminated,

the once powerful Catawbas. When, in 1144, the Six Nations ceded a portion

of their lands to Virginia, they insisted on the continuance of a free war-path

through the ceded territory.

110

the French, they are men-they are fortifying every where; but, we are ashamed to say it, you are like women, bare and open, without any fortifications."(1)

The head of Lake George was the theater of a terrible massacre in 1757. Lord Loudon, a man of no energy of character, and totally deficient in the requisites for a military leader, was appointed that year governor of Virginia, and commander-in-chief of all the British forces in North America. A habit of procrastination, and his utter indecision, thwarted all his active intentions, if he ever had any, and, after wasting the whole season in getting here and preparing to do something, he was recalled by Pitt, then prime minister, who gave as a reason for appointing Lord Amherst in his place, that the minister never heard from him, and could not tell what he was doing.(2)

Opposed to him was the skillful and active French commander, the Marquis Montcalm, who succeeded Dieskau. Early in the spring he made an attempt to capture Fort William, (March 16, 1757.)Henry. He passed up Lake George on St. Patrick's eve, landed stealthily behind Long Point, and the next afternoon appeared suddenly before the fort. A part of the garrison made a vigorous defense, and Montcalm succeeded only in burning some buildings and vessels which were out of reach of the guns at the fort." He returned to Ticonderoga, at which post and at Crown Point he mustered all his forces, amounting to nine thousand men, including Canadians and Indians, and in July prepared for another attempt to capture Fort William Henry.

General Webb, who was commander of the forces in that quarter, was at Fort Edward with four thousand men. He visited Fort William Henry under an escort of two hundred men commanded by Major Putnam, and while there he sent that officer with eighteen Rangers down the lake, to ascertain the position of the enemy on Champlain. They were discovered to be more numerous than was supposed, for the islands at the entrance of Northwest Bay were swarming with French and Indians. Putnam returned, and begged General Webb to let him go down with his Rangers in full force and attack them, but he wa, allowed only to make another reconnaissance, and bring off two boats and their crews which he left fishing. The enemy gave chase in canoes, and at times nearly surrounded them, hut they reached the fort in safety.

Webb caused Putnam to administer an oath of secrecy to his Rangers respecting the proximity of the enemy, and then ordered him to escort him back immediately to Fort Edward. This order was so repugnant to Putnam, both as to its perfidy and unsoldierly character, that he ventured to remonstrate by saying, "I hope your excellency does not intend to neglect so fair an opportunity of giving battle should the enemy presume to land." Webb coolly and cowardly replied, " What do you think we should do here?" The near approach of the enemy was cruelly concealed from the garrison, and under his escort the general returned to Fort Edward. The next day he sent Colonel Monroe with a regiment to re-enforce and to take command of the garrison at Lake George.

Montcalm, with more than nine thousand men, and a powerful train of artillery, landed

1 Reported for the Gentlemen's Magazine, London,

1755.

2 This is asserted by Dr. Franklin in his Autobiography (Sparks's Life,

219), where he gives an anecdote illustrative of the character of Loudon.

Franklin had occasion to go to his office in New York, where he met a Mr.

Innis, who had brought dispatches from Philadelphia from Governor Denny,

and was awaiting his lordship's answer, promised the following day. A fortnight

afterward he met Innis, and expressed his surprise at his speedy return.

But he had not yet gone, and averred that he had called at Loudon's office

every morning during the fortnight, but the letters were not yet ready.

" Is it possible," said Franklin, "when he is so great a

writer? I see him constantly at his escritoire." "Yes," said

Innis, "but he is like St. George on the signs, always on horseback,

but never rides forward."

3 The garrison and fort were saved by the vigilance of Lieutenant Stark,

who, in the absence of Rogers, had command of the Rangers, a large portion

of which were Irishmen. On the evening of the 16th he overheard some of

these planning a celebration of St. Patrick's (the following day). He ordered

the sutler not to issue spirituous liquors the next day without a written

order. When applied to he pleaded a lame wrist as an excuse for not writing,

and his Rangers were kept sober. The Irish in the regular regiments got

drunk, as usual on such an occasion. Montcalm anticipated this, and planned

his attack on the night of St. Patrick's day. Stark, with his sober Rangers,

gallantly defended and saved the fort.

111

at the head of the lake, and beleaguered the garrison, consisting of less than three thousand men.(1) He sent in proposals to Monroe for a surrender of the fort, urging his humane desire to prevent the bloodshed which a stubborn resistance would assuredly cause. Monroe, confidently expecting re-enforcements from Webb, refused to listen to any such proposals. Thc French then commenced the siege, which lasted six consecutive days, without much slaughter on either side. Expresses were frequently sent to General Webb in the meanwhile, imploring aid, but he remained inactive and indifferent in his camp at Fort Edward. General Johnson was at last allowed to march, with Putnam and his Rangers, to the relief of the beleaguered garrison; but when about three miles from Fort Edward, Webb recalled them, and sent a letter to Monroe, saying he could render him no assistance, and advising him to surrender. This letter was intercepted by Montcalm, and gave him great joy, for he had been informed by some Indians of the movements of the provincials under Johnson and Putnam, who represented them to be as numerous as the leaves on the trees. Alarmed at this, Montcalm was beginning to suspend the operations of the siege preparatory to a retreat, when the letter from the pusillanimous Webb fell into his hands. He at once sent it in to Monroe, with proposals for an immediate surrender.

Monroe saw that his case was hopeless, for two of his cannon had bursted, and his ammunition and stores were nearly exhausted. Articles of capitulation were agreed upon, and, under promise of protection, the garrison marched out of the fort preparatory to being escorted to Fort Edward.(2)

The savages, two thousand warriors in number, were enraged at the terms of capitulation, for they were induced to serve in this expedition by a promise of plunder. (3) This was denied them, and they felt at liberty to throw off all restraint. As soon as the last man left the gate of the fort, they raised the hideous war-whoop, and fell upon the English with the fury of demons. The massacre was indiscriminate and terrible, and the French were idle spectators of the perfidy of their allies. They refused interference, withheld the promised escort, and the savages pursued the poor Britons with great slaughter, half way to Fort Edward.(4)Fifteen hundred of them were butchered or carried into hopeless captivity. Montcalm utterly disclaimed all connivance, and declared his inability to prevent the massacre without ordering his men to fire upon the Indians. But it left a deep stain upon his otherwise humane character, and the indignation excited by the event aroused the English colonists to more united and vigorous action.

Montcalm burned and otherwise destroyed every thing connected with the fortification. (August 9, 1757.) Major Putnam, who had been sent with his Rangers from Fort Edward to watch the movements of Montcalm, reached Lake George just as the rear of the enemy left the shore, and truly awful was the scene there presented, as described by himself: "The fort was entirely demolished; the barracks, out-houses, and buildings were a heap of ruins; the cannon, stores, boats, and vessels were all carried away. The fires were still burning, the smoke and stench offensive and suffocating. Innumerable fragments, human skulls and bones, and carcasses half consumed, were still frying and broiling in the decaying fires.

1 The place where Montcalm landed is a little north of the

Lake House, at Caldwell, and about a mile from the site of the fort.

2 It was stipulated, 1st. That the garrison should march out with their

arms and baggage; 2d. Should be escorted to Fort Edward by a detachment

of French troops, and should not serve against the French for a term of

eighteen months; 3d. The works and all the warlike stores should be delivered

to the French, 4th. That the sick and wounded of the garrison should remain

under the protection of Montcalm, and should he permitted to return as soon

as they were recovered.

3 Dr. Belknap.

4 The defile through which the English retreated, and in which so many were

slaughtered, is called the Bloody Defile. It is a deep gorge between the

road from Glenn's Falls to Lake George and the high range of hills northward,

called the French Mountain. In excavations for the plank road near the defile

a large number of skeletons were exhumed. I saw the skull of one, which

was of an enormous size, at least one third larger than any other human

head I ever saw. The occipital portion exhibited a long fracture, evidently

made by a tomahawk.

Chapter Five, part two