CHAPTER I

THE HUDSON, FROM THE WILDERNESS TO THE SEA.

Tis

proposed to present, in a series of sketches with pen and pencil, pictures

of the Hudson River, from its birth among the mountains to its marriage with

the ocean. It is by far the most interesting river in America, considering

the beauty and magnificence of its scenery, its natural, political, and social

history, the agricultural and mineral treasures of its vicinage, the commercial

wealth hourly floating upon its bosom, and the relations of its geography

and topography to some of the most important events in the history of the

Western hemisphere.

Tis

proposed to present, in a series of sketches with pen and pencil, pictures

of the Hudson River, from its birth among the mountains to its marriage with

the ocean. It is by far the most interesting river in America, considering

the beauty and magnificence of its scenery, its natural, political, and social

history, the agricultural and mineral treasures of its vicinage, the commercial

wealth hourly floating upon its bosom, and the relations of its geography

and topography to some of the most important events in the history of the

Western hemisphere.

High upon the walls of the governor's room in the New York City Hall is a dingy painting of a broad-headed, short-haired, sparsely-bearded man, with an enormous ruffle about his neck, and bearing the impress of an intellectual, courtly gentleman of the days of King James the First of England. By whom it was painted nobody knows, but conjecture shrewdly guesses that it was delineated by the hand of Paul Van Someren, the skilful Flemish artist who painted the portraits of many persons of distinction in Amsterdam and London, in the reign of James, and died in the British capital four years before that monarch. We are well assured that it is the portrait of an eminent navigator, who, in that remarkable year in the history of England and America, one thousand six hundred and seven, "met certaine worshippeful merchants of London," in the parlour of a son of Sir Thomas Gresham, in Bishopsgate Street, and bargained concerning a proposed voyage in search of a north-east passage to India, between the icy and rock-bound coasts of Nova Zembla and Spitzbergen.

That navigator was HENRY HUDSON, a friend of Captain John Smith, a man of science and liberal views, and a pupil, perhaps, of Drake, or Frobisher, or Grenville, in the seaman's art. On May-day morning he knelt in the church of St. Ethelburga, and partook of the Sacrament; and soon afterward he left the Thames for the circumpolar waters. During two voyages he battled the ice-pack manfully off the North Cape, but without success: boreal frosts were too intense for the brine, and cast impenetrable ice-barriers across the eastern pathway of the sea. His employers praised the navigator's skill and courage, but, losing faith in the scheme, the undertaking was abandoned. Hudson went to Holland with a stout heart; and the Dutch East India Company, then sending their uncouth argosies to every sea, gladly employed "the bold Englishman, the expert pilot, and famous navigator," of whose fame they had heard so much.

At the middle of March, 1609, Hendrick, as the Dutch called him, sailed from Amsterdam in a yacht of ninety tons, named the Half-Moon, manned with a choice crew, and turned. his prow, once more, toward Nova Zembla. Again ice, and fogs, and fierce tempests, disputed his passage, and he steered westward, passed Cape Farewell, and, on the 2nd of July, made soundings upon the banks of Newfoundland. He sailed along the coast to the fine harbour of Charleston, in South Carolina, in search of a north-west passage "below Virginia," spoken of by his friend Captain Smith. Disappointed, he turned northward, discovered Delaware Bay, and on the 3rd of September anchored near Sandy Hook. On the 11th he passed through the Narrows into the present bay of New York, and from his anchorage beheld, with joy, wonder, and hope, the waters of the noble Mahicannituck, or Mohegan River, flowing from the high blue hills on the north. Toward evening the following day he entered the broad stream, and with a full persuasion, on account of tidal currents, that the river upon which he was borne flowed from ocean to ocean, he rejoiced in the dream of being the leader to the long-sought Cathay. But when the magnificent highlands, fifty miles from the sea, were passed, and the stream narrowed and the water freshened, hope failed him. But the indescribable beauty of the virgin land through which he was voyaging, filled his heart and mind with exquisite pleasure; and as deputations of dusky men came from the courts of the forest sachems to visit him, in wonder and awe, he seemed transformed into some majestic and mysterious hero of the old sagas of the North.

The yacht anchored near the shore where Albany now stands, but a boat's crew, accompanied by Hudson, went on, and beheld the waters of the Mohawk foaming among the rocks at Cohoes. Then back to New York Bay the navigator sailed; and after a parting salutation with the chiefs of the Manhattans at the mouth of the river, and taking formal possession of the country in the name of the government of Holland, he departed for Europe, to tell of the glorious region, filled with fur-bearing animals, beneath the parallels of the North Virginia Charter. He landed in England, but sent his log-book, charts, and a full account of his voyage to his employers at Amsterdam. King James, jealous because of the advantages which the Dutch might derive from these discoveries, kept Hudson a long time in England; hut the Hollanders had all necessary information, and very soon ships of the company and of private adventurers were anchored in the waters of the Mahicannituck, and receiving the wealth of the forests from the wild men who inhabited them. The Dutchmen and the Indians became friends, close-bound by the cohesion of trade. The river was named Mauritius, in honour of the Stadtholder of the Netherlands, and the seed of a great empire was planted there.

The English, in honour of their countryman who discovered it, called it Hudson's River, and to the present time that title has been maintained; but not without continual rivalry with that of North River, given it by the early Dutch settlers after the discovery of the Delaware, which was named South River. It is now as often called North River as Hudson in the common transactions of trade, names of corporations, &c. ; but these, with Americans, being convertible titles, produce no confusion.

For one hundred and fifty years after its discovery, the Hudson, above Albany, was little known to white men, excepting hunters and trappers, and a few isolated settlers; and the knowledge of its sources among lofty alpine ranges is one of the revelations made to the present century, and even to the present generation. And now very few, excepting the hunters of that region, have personal knowledge of the beauty and wild grandeur of lake, and forest, and mountain, out of which spring the fountains of the river we are about to describe. To these fountains and their forest courses I made a pilgrimage toward the close of the summer of 1859, accompanied by Mrs. Lossing and Mr. S. M. Buckingham, an American gentleman, formerly engaged in mercantile business in Manchester, England, and who has travelled extensively in the East.

Our little company; composed of the minimum in the old prescription for a dinner-party-not more than the Muses nor less than the Graces--left our homes, in the pleasant rural city of Poughkeepsie, on the Hudson, for the wildernesss of northern New York, by a route which we are satisfied, by experience and observation, to be the best for the tourist or sportsman bound for the head waters of that river, or the high plateau northward and westward of them, where lie in solitary beauty a multitude of lakes filled with delicious fish, and embosomed in primeval forests abounding with deer and other game. We travelled by railway about one hundred and fifty miles to Whitehall, a small village in a rocky gorge, where Wood Creek leaps in cascades into the head of Lake Champlain. There, we tarried until the following morning, and at ten o'clock embarked upon a steamboat for Port Kent-our point of departure for the wild interior, far down the lake on its western border. The day was fine, and the shores of the lake, clustered with historical associations, presented a series of beautiful pictures; for they were rich with forest verdure, the harvests of a fruitful seed-time, and thrifty villages and farmhouses. Behind these, on the east, arose the lofty ranges of the Green Mountains, in Vermont; and on the west were the Adirondacks of New York, whither we were journeying, their clustering peaks, distant and shadowy, bathed in the golden light of a summer afternoon.

Lake Champlain is deep and narrow, and one hundred and forty miles in length. It received its present name from its discoverer, the eminent French navigator, Samuel Champlain, who was upon its waters the same year when Hudson sailed up the river which bears his name. Champlain came from the north, and Hudson from the south; and they penetrated the wilderness to points within a hundred miles of each other. Long before, the Indians had given it the significant title of Can-i-a-ae-ri Gua-run-te, the Door of the Country. The appropriateness of this name will be illustrated hereafter.

It was evening when we arrived at Port Kent. We remained until morning with a friend (Winslow C. Watson, Esq., a descendant of Governor Winslow, who came to New England in the Mayflower), whose personal explorations and general knowledge of the region we were about to visit, enabled him to give us information of much value in our subsequent course. With himself and family we visited the walled banks of the Great Au Sable, near Keeseville, and stood with wonder and awe at the bottom of a terrific gorge in sandstone, rent by an earthquake's power, and a foaming river rushing at our feet. The gorge, for more than a mile, is from thirty to forty feet in width, and over one hundred in depth. This was our first experience. of the wild scenery of the north. The tourist should never pass it unnoticed.

Our direct route from Keeseville lay along the picturesque valley of the Great Au Sable River, a stream broken along its entire course into cascades, draining about seven hunched square miles of mountain country, and falling four thousand six hundred feet in its passage from its springs to Lake Champlain, a distance of only about forty miles. We made a detour of a few miles at Keeseville for a special purpose, entered the valley at twilight, and passed along the margin of the rushing waters of the Au Sable six miles to the Forks, where we remained until morning. The day dawned gloomily, and for four hours we rode over the mountains toward the Saranac River in a drenching rain, for which we were too well prepared to experience any inconvenience. At Franklin Falls, on the Saranac, in the midst of the wildest mountain scenery, where a few years before a forest village had been destroyed by fire, we dined upon trout and venison, the common food of the wilderness, and then rode on toward the Lower Saranac Lake, at the foot of which we were destined to leave roads, and horses, and industrial pursuits behind, and live upon the solitary lake and river, and in the almost unbroken woods.

The clouds were scattered early in the afternoon, but lay in heavy masses upon the summits of the deep blue mountains, and deprived us of the pleasure to be derived from distant views in the amphitheatre of everlasting hills through which we were journeying. Our road was over a high rolling country, fertile, and in process of rapid clearing. The loghouses of the settlers, and the cabins of the charcoal burners, were frequently seen; and in a beautiful valley, watered by a branch of the Saranac, we passed through a pleasant village called Bloomingdale. Toward evening we reached the sluggish outlet of the Saranac Lakes, and at a little before sunset our position reined up at Baker's Inn, two miles from the Lower Lake, and fifty-one from Port Kent. To the lover and student of nature, the artist and the philosopher, the country through which we had passed, and to which only brief allusion may here be made, is among the most inviting spots upon the globe, for magnificent and picturesque scenery, mineral wealth, and geological wonders, abound on every side.

At Baker's Inn every comfort for a reasonable man was found. There we procured guides, boats, and provisions for the wilderness; and at a little past noon on the following day we were fairly beyond the sounds of the settlements, upon a placid lake studded with islands, the sun shining in unclouded splendour, and the blue peaks of distant mountains looming above the dense forests that lay in gloomy grandeur between us and their rugged acclivities.

Our party now consisted of five, two, guides having been added to it. One of them was a son of Mr. Baker, the other a pure-blooded Penobscot Indian from the state of Maine. Each had a light boat-so light that he might carry it upon his shoulders at portages, or the intervals between the navigable portIons of streams or lakes. In one of these was borne our luggage, provisions, and Mr. Buckingham, and in the other Mrs. Lossing and myself.

The

Saranac Lakes are three in number, and lie on the south-eastern borders of

Franklin County, north of Mount Seward. They are known as the Upper, Round,

and Lower. The latter, over which we first voyaged, is six miles in length.

From its head we passed along a winding and narrow river, fringed with rushes,

lilies, and moose-head plants, almost to the central or Round Lake, where

we made a portage of a few rods, and dined beneath a towering pine-tree. While

there, two deerhounds, whose voices we had heard in the forest a few minutes

before, came dashing up, dripping with the lake water through which they had

been swimming, and, after snuffing the scent of our food wistfully for a moment,

disappeared as suddenly. We crossed Round Lake; three and a half miles, and

went up a narrow river about a mile, to the falls at the outlet of the Upper

Saranac. Here, twelve miles from our embarkation, was a place of entertainment

for tourists and sportsmen, in thc midst of a small clearing. A portage of

an eighth of a mile, over which the boats and luggage were carried a upon

a waggon, brought us to the foot of the Upper Lake. On this dark, wild sheet

of water, thirteen miles in length, we embarked toward the close of the day,

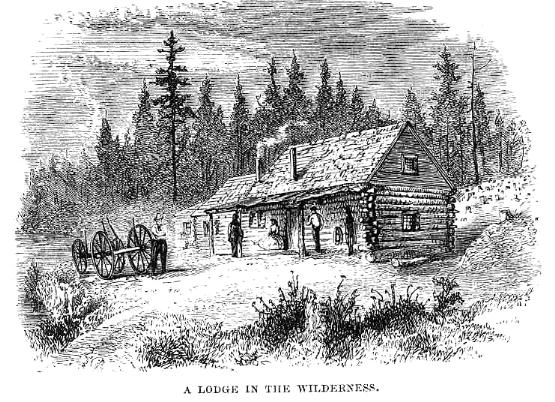

and just before sunset reached the lodge of Corey, a hunter and guide well

known in all that region. It stood near the gravelly shore of a beautiful

bay with a large island in its bosom, heavily wooded with evergreens. It was

Saturday evening, and here, in this rude house of logs, where we had been

pleasantly received by a modest and genteel young woman, we resolved to spend

the Sabbath. Nor did we regret our resolution. We found good wilderness accommodations;

and at midnight the hunter came with his dogs from a long tramp in the woods,

bringing a fresh-killed deer upon his shoulders.

The

Saranac Lakes are three in number, and lie on the south-eastern borders of

Franklin County, north of Mount Seward. They are known as the Upper, Round,

and Lower. The latter, over which we first voyaged, is six miles in length.

From its head we passed along a winding and narrow river, fringed with rushes,

lilies, and moose-head plants, almost to the central or Round Lake, where

we made a portage of a few rods, and dined beneath a towering pine-tree. While

there, two deerhounds, whose voices we had heard in the forest a few minutes

before, came dashing up, dripping with the lake water through which they had

been swimming, and, after snuffing the scent of our food wistfully for a moment,

disappeared as suddenly. We crossed Round Lake; three and a half miles, and

went up a narrow river about a mile, to the falls at the outlet of the Upper

Saranac. Here, twelve miles from our embarkation, was a place of entertainment

for tourists and sportsmen, in thc midst of a small clearing. A portage of

an eighth of a mile, over which the boats and luggage were carried a upon

a waggon, brought us to the foot of the Upper Lake. On this dark, wild sheet

of water, thirteen miles in length, we embarked toward the close of the day,

and just before sunset reached the lodge of Corey, a hunter and guide well

known in all that region. It stood near the gravelly shore of a beautiful

bay with a large island in its bosom, heavily wooded with evergreens. It was

Saturday evening, and here, in this rude house of logs, where we had been

pleasantly received by a modest and genteel young woman, we resolved to spend

the Sabbath. Nor did we regret our resolution. We found good wilderness accommodations;

and at midnight the hunter came with his dogs from a long tramp in the woods,

bringing a fresh-killed deer upon his shoulders.

Our first Sabbath in the wilderness was a delightful one. It was a perfect summer-day, and all around us were freshness and beauty. We were alone with God and His works, far away from the abodes of men; and when at evening the stars came out one by one, they seemed to the communing spirit like diamond lamps hung up in the dome of a great cathedral, in which we had that day worshipped so purely and lovingly. It is profitable, as Bryant says, to

" Go abroad

Upon the paths of Nature, and, when all

Its voices whisper, and its silent things

Are breathing the deep beauty of the world,

Kneel at its ample altar."

Early on Monday morning we resumed our journey. We walked a mile through the fresh woods to the upper of the three Spectacle Ponds, on which we were to embark for the Raquette River and Long Lake. Our boats and luggage were here carried upon a waggon for the last time; after that they were all borne upon the shoulders of the guides. Here we were joined by another guide, with his boat, who was returning to his home, near the head waters of the Hudson, toward which we were journeying. The guides who were conducting us were to leave us at Long Lake, and finding the one who had joined us intelligent and obliging, and well acquainted with a portion of the region we were about to explore, we engaged him for the remainder of our wilderness travel.

The Spectacle Ponds are beautiful sheets of water in the forest, lying near each other, and connected by shallow streams, through which the guides waded and dragged the boats. The outlet-a narrow, sinuous stream, and then shallow, because of a drought that was prevailing in all that northern country-is called "Stony Brook." After a course of three and a half miles through wild and picturesque scenery, it empties into the Raquette River. All along its shores we saw fresh tracks of the deer, and upon its banks the splendid Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), glowing like flame, was seen in many a nook.*

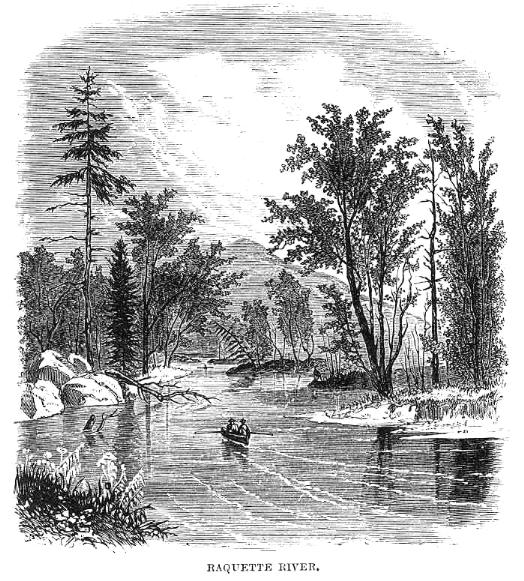

Our entrance into the Raquette was so quiet and unexpected, that we were not aware of the change until we were fairly upon its broader bosom. It is the most beautiful river in all that wild interior. Its

*This superb plant is found from July to October along the shores of the lakes, rivers, and rivulets, and in swamps, all over northern New York. It is perennial, and is borne upon an erect stem, from two to three feet in height. The leaves are long and slender, with a long, tapering base. The flowers are large and very showy. Corolla bright scarlet; the tube slender; segments of the lower lip oblong-lanceolate; filaments red; anthers blue; stigma three-lobed, and at length protruded. It grows readily when transplanted, even in dry soil, and is frequently seen in our gardens. A picture of this plant forms a portion of the design around the initial letter at the head of this chapter.

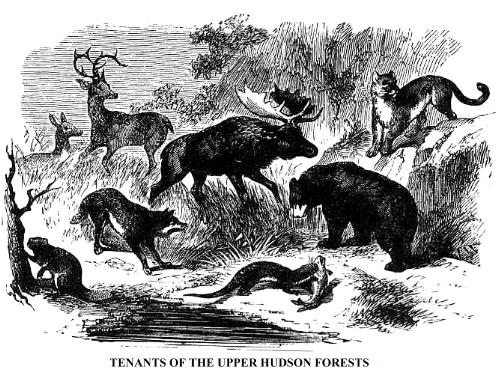

shores are generally low, and extend back some distance in wet prairies, upon which grow the soft maple, the aspen, alder, linden, and: other deciduous trees, interspersed with the hemlock and pine. These fringe its borders, and standing in clumps upon the prairies, in the midst of rank grass, give them the appearance of beautiful de,er parks; and they are really so, for there herds of deer do pasture. We saw their fresh tracks all along the shores, but they are now so continually hunted, that they keep away from the waters whenever a strange sound falls upon their ears. In the deep wilderness through which this dark and rapid river flows, and around the neighbouring lakes, the stately moose yet lingers; and upon St. Regis Lake, north of the Saranac group, two or three families of the beaver-the most rare of all the tenants of these forests might then be found. The otter is somewhat abundant, but the panther has become almost extinct; the wolf is seldom seen, except in winter; and the black bear, quite abundant in the mountain ranges, was shy and invisible to the summer tourist.

The chief source of the Raquette is in Raquette Lake, toward the western part of Hamilton County. Around it the Indians, in the ancient days, gathered on snow-shoes, in winter, to hunt the moose, then found there in large droves; and from that circumstance they named it "Raquet," the equivalent in French for snow-shoe in English.'"

Seven miles from our entrance upon the Raquette, we came to the "Falls," where the stream rushes in cascades over a rocky bed for a mile. At the foot or the rapids we dined, and then walked a mile over a lofty, thickly-wooded hill, to their head, where we re-embarked. Here our guides first carried their boats, and it was surprising to see with what apparent ease our Indian took the heaviest, weighing at least 160 lbs., and with a dog-trot bore it the whole distance, stopping only once. The boat rests upon a yoke, similar to those which water-carriers use in some countries, fitted to the neck and shoulders, and it is thus borne with the ease of the coracle.

At the head of the rapids we met acquaintances-two clergymen in bunting costume-and after exchanging salutations, we voyaged on six miles, to the foot of Long Lake, through which the Raquette flows, like the Rhone through Lake Geneva. This was called by the Indians Inca-pah-chow, or Linden Sea, because the forests upon its shores abounded with the bass-wood or American linden. As we entered that beautiful sheet of water, a scene of indescribable beauty opened upon the vision. The sun was yet a little above the western hills, whose long shadows lay across the wooded intervals. Before us was the lake, calm and translucent as a mirror, its entire length of thirteen miles in view, except where broken by islands, the more distant appearing shadowy in the purple light. The lofty mountain ranges on both sides stretched away into the blue distance, and the slopes of one, and the peak of another, were smoking like volcanoes; the timber being on fire. Near us the groves upon the headlands, solitary trees, rich shrubbery, graceful rushes, the clustering moose-head and water-lily, and the gorgeous cloud-pictures, were perfectly reflected, and produced a scene such as the mortal eye seldom beholds. The sun went down, the vision faded; and, sweeping around a long, marshy point, we drew our boats upon a pebbly shore at

* This is the account of the origin of its name, given by the French Jesuits who first explored that region. Others say that its Indian name, Ni-ha-na-wa-te, means a racket, or noise-noisy river, and spell it Racket. But it is no more noisy than its near neighbour, the Grass River which flows into the St. Lawrence from the bosom of the same wilderness.

twilight, at the foot of a pine-bluff, and proceeded to erect a camp for the night. No human habitation was near, excepting the bark cabin of Bowen, the "Hermit of Long Lake," whose history we have not space to record.

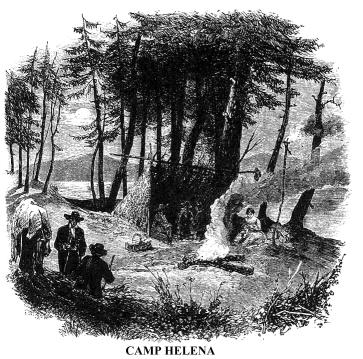

Our

camp was soon constructed. The guides selected a pleasant spot near the foot

of a lofty pine, placed two crotched sticks perpendicularly in the ground,

about eight feet apart, laid a stout pole horizontally across them, placed

others against it in position like the rafters of half a roof, one end upon

the ground, and covered the whole and both sides with the boughs of the hemlock

and pine, leaving the front open. The ground was then strewn with the delicate

sprays of the hemlock and balsam, making a sweet and pleasant bed. A few feet

from the front they built a huge fire, and prepared supper, which consisted

of broiled partridges (that were shot on the shores of the Raquette by one

of the guides), bread and butter, tea and maple sugar. We supped by the light

of a birch-bark torch, fastened to a tall stick. At the close of a moonlight

evening, our fire burning brightly, we retired for the night, wrapped in blanket

shawls, our satchels and their contents serving for pillows, our heads at

the back part of the "camp," and our feet to the fire. The guides

lying near, kept the wood blazing throughout the night. We named the place

Camp Helena, in compliment to the lady of our party.

Our

camp was soon constructed. The guides selected a pleasant spot near the foot

of a lofty pine, placed two crotched sticks perpendicularly in the ground,

about eight feet apart, laid a stout pole horizontally across them, placed

others against it in position like the rafters of half a roof, one end upon

the ground, and covered the whole and both sides with the boughs of the hemlock

and pine, leaving the front open. The ground was then strewn with the delicate

sprays of the hemlock and balsam, making a sweet and pleasant bed. A few feet

from the front they built a huge fire, and prepared supper, which consisted

of broiled partridges (that were shot on the shores of the Raquette by one

of the guides), bread and butter, tea and maple sugar. We supped by the light

of a birch-bark torch, fastened to a tall stick. At the close of a moonlight

evening, our fire burning brightly, we retired for the night, wrapped in blanket

shawls, our satchels and their contents serving for pillows, our heads at

the back part of the "camp," and our feet to the fire. The guides

lying near, kept the wood blazing throughout the night. We named the place

Camp Helena, in compliment to the lady of our party.

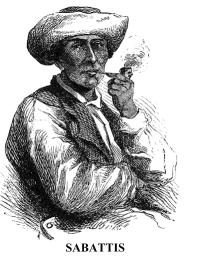

The morning dawned gloriously, and at an early hour we proceeded up the Inca-pah-chow,

in the face of a stiff breeze, ten miles to the mouth of a clear stream, that

came down from one of the burning mountains which we saw the evening before.

A walk of half a mile brought us to quite an extensive clearing, and Houghton's

house of entertainment. There we dismissed our Saranac guides, and despatched

on horseback the one who had joined us on the Spectacle Ponds to the home

of Mitchell Sabattis, a St. Francis Indian, eighteen miles distant, to procure

his services for our tour to the head waters of the Hudson. Sabattis was by

far the best man in all that region to lead the traveler to the Hudson waters,

and the Adirondacks Mountains, for he had lived in that neighbourhood from

his youth, and was then between thirty and forty years of age. He was a grandson

of Sabattis mentioned in history, who, with Natanis, befriended Colonel Benedict

Arnold, while on his march through the wilderness from the Kennebeek to the

Chaudière, in the autumn of 1775, to attack Quebec. Much to our delight

and relief, Sabattis returned with our messenger, for the demand for good

guides was so great, that we were fearful he might be absent on duty with

others.

The morning dawned gloriously, and at an early hour we proceeded up the Inca-pah-chow,

in the face of a stiff breeze, ten miles to the mouth of a clear stream, that

came down from one of the burning mountains which we saw the evening before.

A walk of half a mile brought us to quite an extensive clearing, and Houghton's

house of entertainment. There we dismissed our Saranac guides, and despatched

on horseback the one who had joined us on the Spectacle Ponds to the home

of Mitchell Sabattis, a St. Francis Indian, eighteen miles distant, to procure

his services for our tour to the head waters of the Hudson. Sabattis was by

far the best man in all that region to lead the traveler to the Hudson waters,

and the Adirondacks Mountains, for he had lived in that neighbourhood from

his youth, and was then between thirty and forty years of age. He was a grandson

of Sabattis mentioned in history, who, with Natanis, befriended Colonel Benedict

Arnold, while on his march through the wilderness from the Kennebeek to the

Chaudière, in the autumn of 1775, to attack Quebec. Much to our delight

and relief, Sabattis returned with our messenger, for the demand for good

guides was so great, that we were fearful he might be absent on duty with

others.

Thick clouds came rolling over the mountains from the south at evening, presaging a storm, and the night fell intensely dark. The burning hill above us presented a magnificent appearance in the gloom. The fire was in broken points over a surface of half a mile, near the summit, and the appearance was like a city upon the lofty slope, brilliantly illuminated. It was sad to see the fire sweeping away whole acres of fine timber. But such scenes are frequent in that region, and every bald and blackened hill-top in the ranges is the record of a conflagration.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.