CHAPTER XV.

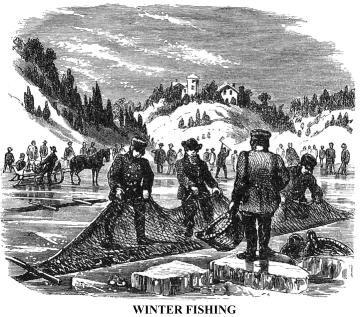

N my way to Tomkins's Cove I encountered other groups

of people, who appeared in positive contrast with the merry skaters on Peek's

Kill Bay. They were sober, thoughtful, winter fishermen, thickly scattered

over the surface, and drawing their long nets from narrow fissures which they

had cut in the ice. The tide was "serving," and many a striped bass,

and white perch, and infant sturgeon at times, were drawn out of their warmer

element to be instantly congealed in the keen wintry air.

These fishermen often find their calling almost as profitable in winter as in April and May, when they draw "schools" of shad from the deep. They generally have a "catch" twice a day when the tide is "slack," their nets being filled when it is ebbing or flowing. They cut fissures in the ice, at right angles with the direction of the tidal currents, eight or ten yards in length, and about two feet in width, into which they drop their nets, sink them with weights, and stretching them to their utmost length, suspend them by sticks that lie across the fissure. Baskets, boxes on hand-sledges, and sometimes sledges drawn by a horse, are used in carrying the "catch" to land. Lower down the river, in the vicinity of the Palisades, when the strength of the ice will allow this kind of fishing, bass weighing from thirty to forty pounds each are frequently caught. These winter fisheries extend from the Donder Berg to Piermont, a distance of about twenty-five miles.

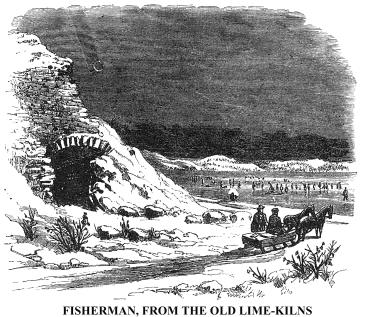

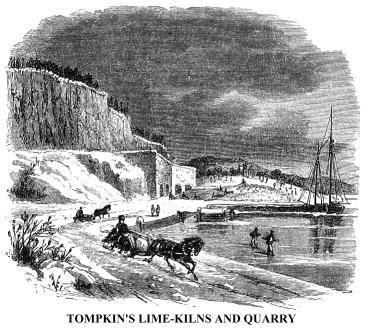

I went on shore at the ruins of an old lime-kiln at the upper edge of Tomkins's Cove, and sketched the fishermen in the distance toward Peek's Kill. It was a tedious task, and, with benumbed fingers, I hastened to the office and store of the Tomkins Lime Company to seek warmth and information. With Mr. Searing, one of the proprietors, I visited the kilns. They are the most extensive works of the kind on the Hudson.

They

are at the foot of an immense cliff of limestone, nearly 200 feet in height,

immediately behind the kilns, and extend more than half a mile along the river.*

The kilns were numerous, and in their management, and the quarrying of the

limestone, about 100 men were continually employed. I saw them on the brow

of the wooded cliff, loosening huge masses and sending them below, while others

were engaged in blasting, and others again in wheeling the lime from the vents

of the kilns to heaps in front, where it is slaked before being placed in

vessels for transportation to market. This is a necessary precaution against

spontaneous combustion.

They

are at the foot of an immense cliff of limestone, nearly 200 feet in height,

immediately behind the kilns, and extend more than half a mile along the river.*

The kilns were numerous, and in their management, and the quarrying of the

limestone, about 100 men were continually employed. I saw them on the brow

of the wooded cliff, loosening huge masses and sending them below, while others

were engaged in blasting, and others again in wheeling the lime from the vents

of the kilns to heaps in front, where it is slaked before being placed in

vessels for transportation to market. This is a necessary precaution against

spontaneous combustion.

Many vessels are employed in carrying away lime, limestone, and "gravel" (pulverized limestone, not fit for the kiln) from Tomkins's Cove, for whose accommodation several small wharves have been constructed.

One million bushels of lime were produced at the kilns each

year. From the quarries, thousands of  tons

of the stone were sent annually to kilns in New Jersey. From 20,000 to 25,000

tons of the "gravel" were used each year in the construction of

macadamized roads. The quarry had been worked almost twenty-five years. From

small beginnings the establishment had grown to a very extensive one. The

dwelling of the chief proprietor was upon the hill above the kiln at the upper

side of the cove; and near the water the houses of the workmen form a pleasant

little village. The country behind, for many miles, is very wild, and almost

uncultivated.

tons

of the stone were sent annually to kilns in New Jersey. From 20,000 to 25,000

tons of the "gravel" were used each year in the construction of

macadamized roads. The quarry had been worked almost twenty-five years. From

small beginnings the establishment had grown to a very extensive one. The

dwelling of the chief proprietor was upon the hill above the kiln at the upper

side of the cove; and near the water the houses of the workmen form a pleasant

little village. The country behind, for many miles, is very wild, and almost

uncultivated.

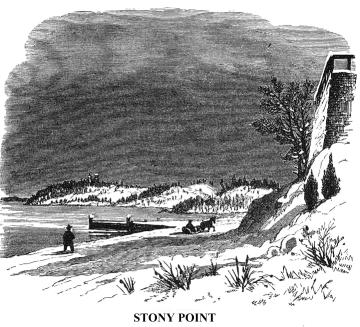

I followed a narrow road along the bank of the river, to the

extreme southern verge of the limestone cliff, near Stony Point, and there

sketched that famous, bold, rocky peninsula from the best spot where a view

of its entire length may be  obtained.

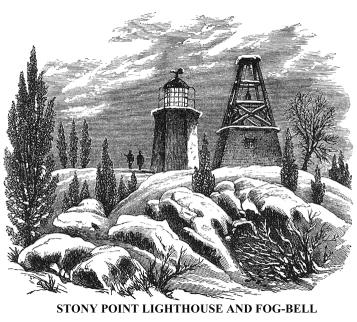

The whole Point is a mass of granite rock, with patches of evergreen trees

and shrubs, excepting on its northern side (at which we are looking in the

sketch), where may be seen a black cliff of magnetic iron one. It is too limited

in quantity to tempt labour or capital to quarry it, and the granite is too

much broken to be very desirable for building purposes. So that peninsula,

clustered with historic associations, will ever remain almost unchanged in

form and feature. A lighthouse, a keeper's lodge, and a fog-bell, occupy its

summit. These stand upon and within the mounds that mark the site of the old

fort which was built there at the beginning of the war for independence.

obtained.

The whole Point is a mass of granite rock, with patches of evergreen trees

and shrubs, excepting on its northern side (at which we are looking in the

sketch), where may be seen a black cliff of magnetic iron one. It is too limited

in quantity to tempt labour or capital to quarry it, and the granite is too

much broken to be very desirable for building purposes. So that peninsula,

clustered with historic associations, will ever remain almost unchanged in

form and feature. A lighthouse, a keeper's lodge, and a fog-bell, occupy its

summit. These stand upon and within the mounds that mark the site of the old

fort which was built there at the beginning of the war for independence.

Stony Point was the theatre of stirring events in the summer

of 1779. The fort there, and Fort  Fayette

on Verplanck's Point, on the opposite side of the river, were captured from

the Americans by Sir Henry Clinton, on the 1st of June of that year. Clinton

commanded the troops in person. These were conveyed by a small squadron under

the command of Admiral Collier. The garrison at Stony Point was very small,

and retired towards West Point on the approach of the British. The fort changed

masters without bloodshed. The victors pointed the guns of the captured fortress,

and cannon and bombs brought by themselves, upon Fort Fayette the next morning.

General Vaughan assailed it in the rear, and the little garrison soon surrendered

themselves prisoners of war.

Fayette

on Verplanck's Point, on the opposite side of the river, were captured from

the Americans by Sir Henry Clinton, on the 1st of June of that year. Clinton

commanded the troops in person. These were conveyed by a small squadron under

the command of Admiral Collier. The garrison at Stony Point was very small,

and retired towards West Point on the approach of the British. The fort changed

masters without bloodshed. The victors pointed the guns of the captured fortress,

and cannon and bombs brought by themselves, upon Fort Fayette the next morning.

General Vaughan assailed it in the rear, and the little garrison soon surrendered

themselves prisoners of war.

These fortresses, commanding the lower entrance to the Highlands, were very important. General Anthony Wayne, known as "Mad Anthony," on account of his impetuosity and daring in the service, was then in command of the Americans in the neighbourhood. Burning with a desire to retake the forts, he applied to Washington for permission to make the attempt. It would be perilous in the extreme. The position of the fort was almost impregnable. Situated upon a high rocky peninsula, an island at high water, and always inaccessible dry-shod, except across a narrow causeway, it was strongly defended by outworks and a double row of abattis. Upon three sides of the rock were the waters of the Hudson, and on the fourth was a morass, deep and dangerous. The cautious Washington considered; when the impetuous Wayne, scorning all obstacles, said, "General, I'll storm hell if you will only plan it!"

Permission to attack Stony Point was given, preparations were

secretly made, and at near midnight, on the 15th of July, Wayne led a strong force of determined men towards the fortress.

They were divided into two columns, each led by a forlorn hope of twenty picked

men. They advanced undiscovered until within pistol-shot of the picket guard

on the heights. The garrison were suddenly aroused from sleep, and the deep

silence of the night was broken by the roll of the drum, the loud cry "To

arms! to arms!" the rattle of musketry from the ramparts and behind the

abattis, and the rear of cannon charged with deadly grape-shot. In

the face of this terrible storm the Americans made their way, by force of

bayonet, to the centre of the works. Wayne was struck upon the head by a musket

ball that brought him upon his knees. "March on!" he cried. "Carry

me into the fort, for I will die at the head of my column!" The wound

was not very severe, and in an hour he had sufficiently recovered to write

the following note to Washington:--

the 15th of July, Wayne led a strong force of determined men towards the fortress.

They were divided into two columns, each led by a forlorn hope of twenty picked

men. They advanced undiscovered until within pistol-shot of the picket guard

on the heights. The garrison were suddenly aroused from sleep, and the deep

silence of the night was broken by the roll of the drum, the loud cry "To

arms! to arms!" the rattle of musketry from the ramparts and behind the

abattis, and the rear of cannon charged with deadly grape-shot. In

the face of this terrible storm the Americans made their way, by force of

bayonet, to the centre of the works. Wayne was struck upon the head by a musket

ball that brought him upon his knees. "March on!" he cried. "Carry

me into the fort, for I will die at the head of my column!" The wound

was not very severe, and in an hour he had sufficiently recovered to write

the following note to Washington:--

"Stony Point, 16th July, 1779, 2 o'clock, A.M.

" Dear General,-- The fort and garrison, with Colonel Johnston, are ours. Our officers and men behaved like men who are determined to be free.

"Yours most respectfully,

"Anthony Wayne."

At dawn the next morning the cannon of the captured fort were again turned upon Fort Fayette on Verplanck's Point, then occupied by the British under Colonel Webster. A desultory cannonading was kept up during the day. Sir Henry Clinton sent relief to Webster, and the Americans ceased further attempts to recapture the fortress. They could not even retain Stony Point, their numbers were so few. Washington ordered them to remove the ordnance and stores, and destroy and abandon the works. A large portion of the heavy ordnance was placed upon a galley to be conveyed to West Point. It was sunk by a shot from the Vulture, off Donder Berg Point, and one of the cannon, as we have observed, raised a few years ago by accident, was supposed to have been brought up from the wreck of the ship of the famous Captain Kidd. Congress testified its gratitude to Wayne for his services by a vote of thanks for his "brave, prudent, and soldierly conduct," and also ordered a gold medal, emblematic of the event, to be struck and presented to him. Copies of this medal, in silver, were given to two of the subordinate officers engaged in the enterprise.

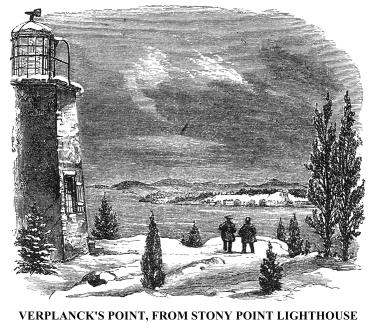

I climbed to the summit of Stony Point along a steep, narrow,

winding road from a deserted wharf,  the

snow almost knee-deep in some places. The view was a most interesting one.

As connected with the history and traditions of the country, every spot upon

which the eye rested was classic ground, and the waters awakened memories

of many legends. Truthful chronicles and weird stories in abundance are associated

with the scenes around. Arnold's treason and André's capture and death,

the "storm ship" and the "bulbous-bottomed Dutch goblin that

keeps the Donder Berg," already mentioned, and a score of histories and

tales pressed upon the attention and claimed a passing thought. But the keen

wintry wind sweeping over the Point kept the mind prosaic. There was no poetry

in the attempts to sketch two or three of the most prominent scenes; and I

resolved, when that task was accomplished, to abandon the amusement until

the warm sun of spring should release the waters from their Boreal chains,

clothe the earth in verdure, and invite the birds from the balmy south to

build their nests in the branches where the snow-heaps then lay.

the

snow almost knee-deep in some places. The view was a most interesting one.

As connected with the history and traditions of the country, every spot upon

which the eye rested was classic ground, and the waters awakened memories

of many legends. Truthful chronicles and weird stories in abundance are associated

with the scenes around. Arnold's treason and André's capture and death,

the "storm ship" and the "bulbous-bottomed Dutch goblin that

keeps the Donder Berg," already mentioned, and a score of histories and

tales pressed upon the attention and claimed a passing thought. But the keen

wintry wind sweeping over the Point kept the mind prosaic. There was no poetry

in the attempts to sketch two or three of the most prominent scenes; and I

resolved, when that task was accomplished, to abandon the amusement until

the warm sun of spring should release the waters from their Boreal chains,

clothe the earth in verdure, and invite the birds from the balmy south to

build their nests in the branches where the snow-heaps then lay.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.