CHAPTER XVIII.

E have already observed the progress of Arnold's treason, from its inception

to his conference with André at the house of Joshua Hett Smith. There

we left them, André being in possession of sundry valuable papers,

revealing the condition of the post to be surrendered, and a pass. He remained

alone with his troubled thoughts all day. The Vulture, as we have seen, had

dropped down the river, out of sight, in consequence of a cannonade from a

small piece of ordnance upon the extremity of Teller's Point, sent there for

the purpose by Colonel Henry Livingston, who was in command at Verplanck's

Point, a few miles above.

In the afternoon André solicited Smith to take him back to the Vulture. Smith refused, with the false plea of illness--but he offered to travel half the night with the adjutant-general if he would take the land route. There was no alternative, and André was compelled to yield to the force of circumstances. He consented to cross the King's Ferry (from Stony to Verplanck's Point), and make his way back to New York by land. He exchanged his military coat for a citizen's dress, placed the papers received from Arnold in his stockings under his feet, and at a little before sunset on the evening of the 22nd of September, accompanied by Smith and a negro servant, all mounted, made his way towards King's Ferry, bearing the following pass, in the event of his being challenged within the American lines:--

"Head-quarters, Robinson's House, Sept. 22, 1780.

"Permit Mr. John Anderson to pass the Guards to the White Plains, or below, if he chooses, he being on public business by my direction.

"B. Arnold, Major-General."

At twilight they passed through the works at Verplanck's Point, unsuspected, and then turned their faces towards the White Plains, the interior route to New York. André was moody and silent. He had disobeyed the orders of his commander by receiving papers, and was involuntarily a spy, in every sense of the word, within the enemy's lines. Eight miles from Verplanck's they were hailed by a sentinel. Arnold's pass was presented, and the travelers were about to pass on, when the officer on duty advised them to remain until morning, because of dangers on the road. After much persuasion, André consented to remain, but passed a sleepless night. At an early hour the party were in the saddle, and at Pine's Bridge over the Croton, André, with a lighter heart, parted company with Smith and his servant, having been assured that he was then upon the neutral ground, beyond the reach of the American patrolling parties.

André had been warned to avoid the Cow Boys. These were bands of Tory marauders who infested the neutral ground. He was told that they were more numerous upon the Tarrytown road than that which led to the White Plains. As these were friends of the British, he resolved to travel the Tarrytown or river road. He felt assured that if he should fall into the hands of the Cow Boys, he would be taken by them to New York, his destination. This change of route was his fatal mistake.

On the morning when André crossed Pine's Bridge, a little band of seven volunteers went out near Tarrytown to prevent the Cow Boys driving the cattle to New York, and to arrest any suspicious travelers upon the highway. Three of these--Paulding, Van Wart, and Williams--were under the shade of a clump of trees, near a spring on the borders of the stream just mentioned, and now known by the name of André's Brook, playing cards, when a stranger appeared on horseback, a short distance up the road. His dress and manner were different from ordinary travelers seen in that vicinity, and they determined to step out and question him. Paulding had lately escaped from captivity in New York, in the dress of a German Yager, the mercenaries in the employment of the British; and on seeing him, André, thereby deceived, exclaimed, "Thank God! I am once more among friends." But Paulding presented his musket, and ordered him to stop. "Gentlemen," said André, "I hope you belong to our party?" "What party?" asked Paulding. "The Lower Party" (meaning the British), André replied. "I do," said Paulding; when André said, "I am a British officer, out in the country on particular business, and I hope you will not detain me a minute." Paulding told him to dismount, when André, conscious of his mistake, exclaimed, "My God! I must do anything to get along;" and with a forced good-humour, pulled out General Arnold's pass. Still they insisted upon his dismounting, when he warned them not to detain him, as he was on public business for the General. They were inflexible. They said there were many bad people on the road, and they did not know but he might be one of them. He dismounted, when they took him into a thicket, and searched him. They found nothing to confirm their suspicions that he was not what he represented himself to be. They then ordered him to pull off his boots, which he did without hesitation, and they were about to allow him to dress himself, when they observed something in his stockings under his feet. When these were removed they discovered the papers which Arnold had put in his possession. Finding himself detected, he offered them bribes to let him go. They refused; and he was conducted to the nearest American post, and delivered to a commanding officer. That officer, with strange obtuseness of perception, was about to send the prisoner to General Arnold with a letter detailing the circumstances of his arrest, when Major Tallmadge, a bright and vigilant officer, protested against the measure, and expressed his suspicious of Arnold's fidelity. But Jamieson, the commander, only half yielded. He detained the prisoner, but sent the letter to Arnold. That was the one which the traitor received while at breakfast at Beverly (Robinson's House), and which caused his precipitate flight to the Vulture. The circumstances of that flight have already been narrated.

André wrote a letter to Washington, briefly but frankly detailing the events of his mission, and concluded, after relating how he was conducted to Smith's House, and changed his clothes, by saying, "Thus, as I have had the honour to relate, was I betrayed (being adjutant-general of the British army) into the vile condition of an enemy in disguise within your posts."

Washington

ordered André to be sent first to West Point, and then to Tappan, an

inland hamlet on the west side of the Hudson opposite Tarry-town, then the

head-quarters of the American army. There, at his own quarters, he summoned

a board of general officers on the 29th of September, and ordered them to

examine into the case of Major André, and report the result. He also

directed them to give their opinion as to the light in which the prisoner

ought to be regarded, and the punishment that should be inflicted. André

was arraigned before them, on the same day, in the church not far from Washington's

quarters. He made to them the same truthful statement of facts which he gave

in his letter to Washington, and remarked, "I leave them to operate with

the board, persuaded that you will do me justice." He was remanded to

prison; and after long and careful deliberation, the board reported "That

Major André, adjutant-general of the British army, ought to be considered

as a spy from the enemy, and that agreeably to the law and usage of nations,

it is their opinion he ought to suffer death."

Washington

ordered André to be sent first to West Point, and then to Tappan, an

inland hamlet on the west side of the Hudson opposite Tarry-town, then the

head-quarters of the American army. There, at his own quarters, he summoned

a board of general officers on the 29th of September, and ordered them to

examine into the case of Major André, and report the result. He also

directed them to give their opinion as to the light in which the prisoner

ought to be regarded, and the punishment that should be inflicted. André

was arraigned before them, on the same day, in the church not far from Washington's

quarters. He made to them the same truthful statement of facts which he gave

in his letter to Washington, and remarked, "I leave them to operate with

the board, persuaded that you will do me justice." He was remanded to

prison; and after long and careful deliberation, the board reported "That

Major André, adjutant-general of the British army, ought to be considered

as a spy from the enemy, and that agreeably to the law and usage of nations,

it is their opinion he ought to suffer death."

Washington approved the sentence on the 30th, and ordered his execution the next day at five o'clock in the afternoon. The youth, candour, gentleness, and honourable bearing of the prisoner made a deep impression on the court and the commander-in-chief. Had their decision been in consonance with their feelings instead of their judgments and the stern necessities of war, he would never have suffered death. There was a general desire on the part of the Americans to save him. The only mode was to exchange him for Arnold, and hold the traitor responsible for all the acts of his victim. Sir Henry Clinton was a man of nice honour, and would not be likely to exhibit such bad faith towards Arnold, even to save his beloved adjutant-general. Nor would Washington make such a proposition. He, however, respited the prisoner for a day, and gave others an opportunity to lay an informal proposition of that kind before Clinton. A subaltern went to the nearest British outpost with a letter from Washington to Clinton, containing the official proceedings of the court-martial, and André's letter to the American commander. That subaltern, as instructed, informed the messenger who was to bear the packet to Sir Henry, that he believed André might be exchanged for Arnold. This was communicated to Sir Henry. He refused compliance, but sent a general officer up to the borders of the neutral ground, to confer with one from the American camp on the subject of the innocence of Major André. General Greene, the president of the court, met General Robertson, the commissioner from Clinton, at Dobbs' Ferry. The conference was fruitless of results favourable to André.

The unfortunate young man was not disturbed by the fear of death, but the manner was a subject of great solicitude to him. He wrote a touching letter to Washington, asking to die the death of a soldier, and not that of a spy. Again the stern rules of war interposed. The manner of death must be according to the character given him by the sentence. All hearts were powerfully stirred by sympathy for him. The equity of that sentence was not questioned by military men; and yet, only inexorable expediency at that hour when the Republican cause seemed in the greatest peril, caused the execution of the sentence in his case. The sacrifice had to be made for the public good, and the prisoner was hung as a spy at Tappan at noon on the 2nd of October, 1780.

It is said that Washington never saw Major André, having avoided a personal interview with him from the beginning. Unwilling to give him unnecessary pain, Washington did not reply to his letter asking for the death of a soldier, and the unhappy prisoner was not certain what was to be the manner of his execution, until he was led to the gallows. The lines of Miss Anne Seward, André's friend, commencing,

"O Washington! I thought thee great and good,

Nor knew thy Nero-thirst for guiltless blood,

Severe to use the power that fortune gave,

Thou cool, determined murderer of the brave!"

were unjust, for he sincerely commiserated the fate of the

prisoner, and would have made every proper sacrifice to save him.

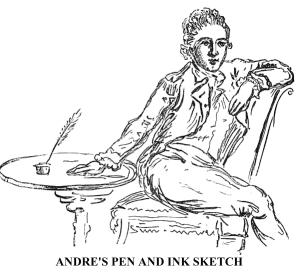

Major André was an accomplished young man, and a clever amateur artist. He was perfectly composed from the time that his fate was made known to him. On the day fixed for his execution, he sketched with pen and ink a likeness of himself sitting at a table, and gave it to the officer of his guard, who had been kind to him. It is preserved in the Trumbull Gallery of pictures, at Yale College, in Connecticut.

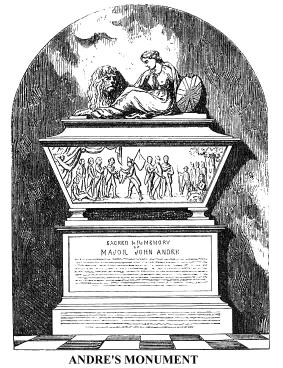

Major André was buried at the place of his execution.

In 1832, his remains were removed, under instructions of his Royal Highness

the Duke of York, by James Buchanan, the British consul at New York, and deposited

in a grave near a monument in Westminster Abbey, erected by his king not long

after his death. It is a mural monument, in the form of a sarcophagus, standing

on a pedestal. It is surmounted by Britannia and her lion. On the front of

the sarcophagus is a basso-relievo, in which is represented General  Washington

and his officers in a tent at the moment when he received the report of the

court of inquiry. At the same time a messenger is seen with a flag, bearing

a letter from André to Washington. On the opposite side is a guard

of Continental soldiers, and the tree on which André was hung. Two

men are preparing the prisoner for execution, in the centre of this design.

At the foot of the tree sit Mercy and Innocence bewailing his fate. Upon a

panel of the pedestal is the following inscription:--"Sacred to the memory

of Major John André, who, raised by his merit at an early period of

his life to the rank of Adjutant-General of the British forces in America,

and employed in an important but hazardous enterprise, fell a sacrifice to

his zeal for his king and country, on the 2nd of October, A.D. 1780, universally

beloved and esteemed by the army in which he served, and lamented even by

his foes. His gracious sovereign, King George the Third, has caused this monument

to be erected." On the base is a record of the removal of his remains

from the banks of the Hudson to their final resting-place near the banks of

the Thames. Such is the sad story, in brief outline, of the closing days of

the accomplished André's life. Arnold, the traitor, was despised even

by those who accepted his treason for purposes of state; and his hand never

afterwards touched the palm of an honourable Englishman. In his own country,

he had ever occupied the "bad eminence" of arch traitor, until the

beginning of the year 1861; others now bear the palm.

Washington

and his officers in a tent at the moment when he received the report of the

court of inquiry. At the same time a messenger is seen with a flag, bearing

a letter from André to Washington. On the opposite side is a guard

of Continental soldiers, and the tree on which André was hung. Two

men are preparing the prisoner for execution, in the centre of this design.

At the foot of the tree sit Mercy and Innocence bewailing his fate. Upon a

panel of the pedestal is the following inscription:--"Sacred to the memory

of Major John André, who, raised by his merit at an early period of

his life to the rank of Adjutant-General of the British forces in America,

and employed in an important but hazardous enterprise, fell a sacrifice to

his zeal for his king and country, on the 2nd of October, A.D. 1780, universally

beloved and esteemed by the army in which he served, and lamented even by

his foes. His gracious sovereign, King George the Third, has caused this monument

to be erected." On the base is a record of the removal of his remains

from the banks of the Hudson to their final resting-place near the banks of

the Thames. Such is the sad story, in brief outline, of the closing days of

the accomplished André's life. Arnold, the traitor, was despised even

by those who accepted his treason for purposes of state; and his hand never

afterwards touched the palm of an honourable Englishman. In his own country,

he had ever occupied the "bad eminence" of arch traitor, until the

beginning of the year 1861; others now bear the palm.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.