CHAPTER XVIII, Part TWO

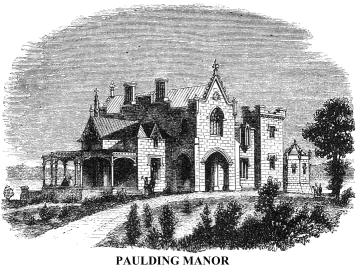

Upon a high and fertile promontory below Tarrytown, may be seen one of the finest and purest specimens of the Pointed Tudor style of domestic architecture in the United States, the residence of Philip R. Paulding, Esq., and called Paulding Manor. It was built in 1840. Its walls are of the Mount Pleasant or Sing Sing marble. The whole outline, ground and sky, is exceedingly picturesque, there being gables, towers, turrets, and pinnacles. There is also a great variety of windows decorated with mullions and tracery; and at one wing is a Port Cochere, or covered entrance for carriages. It has a broad arcaded piazza, affording shade and shelter for promenading. The interior is admirably arranged for convenience and artistic effect. The drawing-room is a spacious apartment, occupying the whole of the south wing. It has a high ceiling, richly groin-arched, with fan tracery or diverging ribs, springing from and supported by columnar shafts. The ceilings of all the apartments of the first story are highly elegant in decoration. "That of the dining-room," says Mr. Downing, "is concavo-convex in shape, with diverging ribs and ramified tracery springing from corbels in the angles, the centre being occupied by a pendant. In the saloon the ribbed ceiling forms two inclined planes. The floor of the second story has a much larger area than that of the first, as the rooms in the former project over the open portals of the latter. The spacious library, over the western portal, lighted by a lofty window, is the finest apartment of this story, with its carved foliated timber roof rising in the centre to twenty-five feet." The dimensions of this room are thirty-seven by eighteen feet, including an organ gallery. Ever since its erection, Paulding Manor has been the most conspicuous dwelling to be seen by the eye of the voyager on the Lower Hudson.

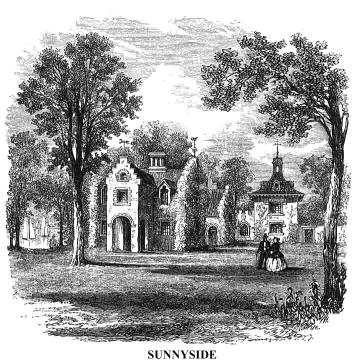

About three miles below Tarrytown is Sunnyside, the residence of the late

Washington Irving. It is reached from the public road by a winding carriage-way

that passes here through rich pastures and pleasant woodlands, and then along

the margin of a dell through which runs a pleasant brook, reminding one of

the merry laughter of children as it dances away riverward, and leaps, in

beautiful cascades and rapids, into a little bay a few yards from the cottage

of Sunnyside. There, more than fifteen years ago, I visited the dear old man

whom the world loved so well, and who so lately was laid beneath the greensward

on the margin of Sleepy Hollow, made classic by his genius. Then I made the

sketch of Sunnyside here presented to the reader. It was a soft, delicious

day in June, when the trees were in full leaf and the birds in full song.

I had left the railway-cars a fourth of a mile below where the germ of a village

had just appeared, and strolled along the iron road to a stile, over which

I climbed, and

About three miles below Tarrytown is Sunnyside, the residence of the late

Washington Irving. It is reached from the public road by a winding carriage-way

that passes here through rich pastures and pleasant woodlands, and then along

the margin of a dell through which runs a pleasant brook, reminding one of

the merry laughter of children as it dances away riverward, and leaps, in

beautiful cascades and rapids, into a little bay a few yards from the cottage

of Sunnyside. There, more than fifteen years ago, I visited the dear old man

whom the world loved so well, and who so lately was laid beneath the greensward

on the margin of Sleepy Hollow, made classic by his genius. Then I made the

sketch of Sunnyside here presented to the reader. It was a soft, delicious

day in June, when the trees were in full leaf and the birds in full song.

I had left the railway-cars a fourth of a mile below where the germ of a village

had just appeared, and strolled along the iron road to a stile, over which

I climbed, and  ascended

the bank by a pleasant path to the shadow of a fine old cedar, not far from

the entrance gate. There I rested, and sketched the quaint cottage half shrouded

in English ivy. Its master soon appeared in the porch, with a little fair-haired

boy whom he led to the river bank in search of daisies and buttercups. It

was a pleasant picture, and yet there was a cloud-shadow resting upon it.

His best earthly affections had been buried, long years before, in the grave

with a sweet young lady who had promised to become his bride. Death interposed

between the betrothal and the appointed nuptials. He remained faithful to

that first love. Throughout all the vicissitudes of a long life, in society

and in solitude, in his native land and in foreign countries, on the stormy

ocean and in the repose of quiet homes, he had borne her miniature in his

bosom in a plain golden case, and upon his table, for daily use, always lay

a small Bible, with the name of his lost one, in the delicate handwriting

of a female, upon the title-page. As I looked upon that good man of gentle,

loving nature, a bachelor of sixty-five, I thought of his exquisite picture

of a true woman, in his charming little story of "The Wife," and

wondered whether his own experience had not been in accordance with the following

beautiful passage in his "Newstead Abbey," in which he says:--"An

early, innocent, and unfortunate passion, however fruitful of pain it may

be to the man, is a lasting advantage to the poet. It is a well of sweet and

bitter fancies, of refined and gentle sentiments, of elevated and ennobling

thoughts, shut up in the deep recesses of the heart, keeping it green amidst

the withering blights of the world, and by its casual gushings and overflowings,

recalling at times all the freshness, and innocence, and enthusiasm of youthful

days."

ascended

the bank by a pleasant path to the shadow of a fine old cedar, not far from

the entrance gate. There I rested, and sketched the quaint cottage half shrouded

in English ivy. Its master soon appeared in the porch, with a little fair-haired

boy whom he led to the river bank in search of daisies and buttercups. It

was a pleasant picture, and yet there was a cloud-shadow resting upon it.

His best earthly affections had been buried, long years before, in the grave

with a sweet young lady who had promised to become his bride. Death interposed

between the betrothal and the appointed nuptials. He remained faithful to

that first love. Throughout all the vicissitudes of a long life, in society

and in solitude, in his native land and in foreign countries, on the stormy

ocean and in the repose of quiet homes, he had borne her miniature in his

bosom in a plain golden case, and upon his table, for daily use, always lay

a small Bible, with the name of his lost one, in the delicate handwriting

of a female, upon the title-page. As I looked upon that good man of gentle,

loving nature, a bachelor of sixty-five, I thought of his exquisite picture

of a true woman, in his charming little story of "The Wife," and

wondered whether his own experience had not been in accordance with the following

beautiful passage in his "Newstead Abbey," in which he says:--"An

early, innocent, and unfortunate passion, however fruitful of pain it may

be to the man, is a lasting advantage to the poet. It is a well of sweet and

bitter fancies, of refined and gentle sentiments, of elevated and ennobling

thoughts, shut up in the deep recesses of the heart, keeping it green amidst

the withering blights of the world, and by its casual gushings and overflowings,

recalling at times all the freshness, and innocence, and enthusiasm of youthful

days."

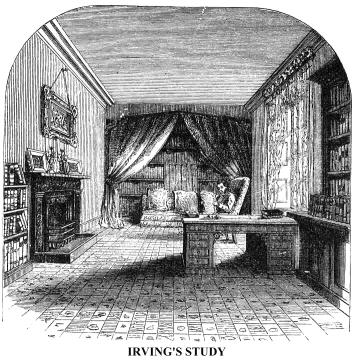

I visited Sunnyside again only a fortnight before the death of Mr. Irving. I found him in his study, a small, quiet room, lighted by two delicately curtained windows, one of which is seen nearest the porch, in our little sketch of the mansion. From that window he could see far down the river; from the other, overhung with ivy, he looked out upon the lawn and the carriage-way from the lane. In a curtained recess was a lounge with cushions, and books on every side. A large easy-chair, and two or three others, a writing-table with many drawers, shelves filled with books, three small pictures, and two neat bronze candelabra, completed the furniture of the room. It was warmed by an open grate of coals in a black variegated marble chimney-piece. Over this were the three small pictures. The larger represents "A literary party at Sir Joshua Reynolds's." The other two were spirited little pen-and-ink sketches, with a little colour--illustrative of scenes in one of the earlier of Mr. Irving's works--"Knickerbocker's History of New York"-- which he picked up in London many years ago. One represented Stuyvesant confronting Risingh, the Swedish governor; the other, Stuyvesant's wrath in council.

Mr.

Irving was in feeble health, but hopeful of speedy convalescence. He expressed

his gratitude because his strength and life had been spared until he completed

the greatest of all his works, his "Life of Washington." "I

have laid aside my pen for ever," he said; "my work is finished,

and now I intend to rest." He was then seven years past the allotted

age of man, yet his mental energy seemed unimpaired, and his genial good-humour

was continually apparent. I took the first course of dinner with him, when

I was compelled to leave to be in time for the next train of cars that would

convey me home. He arose from the table, and passed into the little drawing-room

with me. At the door he took my hand in both of his, and with a pleasant smile

said, "I wish you success in all your undertakings. God bless you."

Mr.

Irving was in feeble health, but hopeful of speedy convalescence. He expressed

his gratitude because his strength and life had been spared until he completed

the greatest of all his works, his "Life of Washington." "I

have laid aside my pen for ever," he said; "my work is finished,

and now I intend to rest." He was then seven years past the allotted

age of man, yet his mental energy seemed unimpaired, and his genial good-humour

was continually apparent. I took the first course of dinner with him, when

I was compelled to leave to be in time for the next train of cars that would

convey me home. He arose from the table, and passed into the little drawing-room

with me. At the door he took my hand in both of his, and with a pleasant smile

said, "I wish you success in all your undertakings. God bless you."

It was the last day of the "Indian summer," in 1859, a soft, balmy, glorious day in the middle of November. The setting sun was sending a blaze of red light across the bosom of Tappan Bay, when I left the porch and followed the winding path down the bank to the railway. There was peacefulness in the aspect of all nature at that hour, and I left Sunnyside, feeling sensibly the influence of a good man's blessing. Only a fortnight afterwards, on a dark, stormy evening, I took up a newspaper at an inn in a small village of the Valley of the Upper Hudson, and read the startling announcement, "Death of Washington Irving." I felt as if a near and dear friend had been snatched away for ever. I was too far from home to be at the funeral, but one of my family, very dear to me, was in the crowd of sincere mourners at his grave, on the borders of Sleepy Hollow. The day was a lovely one on the verge of winter, and thousands stood reverently around, on that sunny slope, while the earth was cast upon the coffin and the preacher uttered the solemn words, "Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust." Few men ever went to the tomb lamented by more sincere friends. From many a pulpit his name was spoken with reverence. Literary and other societies throughout the land expressed their sorrow and respect. A thousand pens wrote eulogies for the press, and Bryant, the poet, his life-long friend, pronounced an impressive funeral oration not long afterwards, at the request of the New York Historical Society, of which Mr. Irving was a member.

I visited Sunnyside again in May, 1860, and after drinking at

the mysterious spring,* strolled along

the brook at the mouth of the glen, where it comes down in cascades before

entering the once beautiful little bay, now cut off from free union with the

river by the railway. The channel was full of crystal water. The tender foliage

was casting delicate shadows where, at this time, there is half twilight under

the umbrageous branches, and the trees are full of warblers. It is a charming

spot, and is consecrated by many memories of Irving and his friends who frequented

this romantic little dell when the summer sun was at meridian.

* This spring is at the foot of the bank on the very brink of the river. "Tradition declares," says Mr. Irving in his admirable story of "Wolfert's Roost," "that it was smuggled over from Holland in a churn by Femmetie Van Blarcon, wife of Goosen Garrett Van Blarcom, one of the first settlers, and that she took it up by night, unknown to her husband, from beside their farm-house near Rotterdam; being sure she should find no water equal to it in the new country--and she was right."

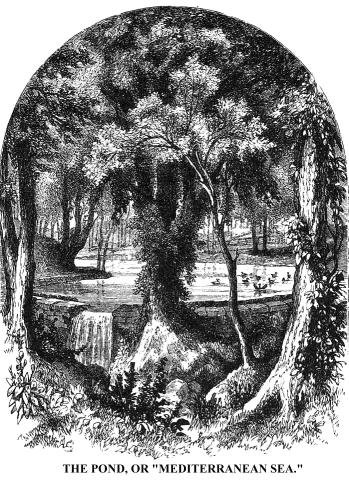

After

sketching the brook at the cascades, I climbed its banks, crossed the lane,

and wandered along a shaded path by a gardener's cottage to a hollow in the

hills, filled with water, in which a bevy of ducks were sporting. This pond,

which Mr. Irving playfully called his "Mediterranean Sea," was made

by damming the stream, and thus a pretty cascade at its outlet was formed.

It is in the shape of the "palm leaf" that comes from the loom.

On one side a wooded hill stretches down to it abruptly, leaving only space

enough for a path, and on others it washes the feet of gentle grassy slopes.

This is one of the many charming pictures to be found in the landscape of

Sunnyside. After strolling along the pathways in various directions, sometimes

finding myself upon the domains of the neighbours of Sunnyside (for no fence

or hedge barriers exist between them), I made my way back to the cottage,

where the eldest and only surviving brother of Mr. Irving, and his daughters,

reside. These daughters were always as children to the late occupant, and

by their affection and domestic skill they made his home a delightful one

to himself and friends. But the chief light of that dwelling is removed, and

there are shadows at Sunnyside that fall darkly upon the visitor who remembers

the sunshine of its former days, for, as his friend Tuckerman wrote on the

day after the funeral,--

After

sketching the brook at the cascades, I climbed its banks, crossed the lane,

and wandered along a shaded path by a gardener's cottage to a hollow in the

hills, filled with water, in which a bevy of ducks were sporting. This pond,

which Mr. Irving playfully called his "Mediterranean Sea," was made

by damming the stream, and thus a pretty cascade at its outlet was formed.

It is in the shape of the "palm leaf" that comes from the loom.

On one side a wooded hill stretches down to it abruptly, leaving only space

enough for a path, and on others it washes the feet of gentle grassy slopes.

This is one of the many charming pictures to be found in the landscape of

Sunnyside. After strolling along the pathways in various directions, sometimes

finding myself upon the domains of the neighbours of Sunnyside (for no fence

or hedge barriers exist between them), I made my way back to the cottage,

where the eldest and only surviving brother of Mr. Irving, and his daughters,

reside. These daughters were always as children to the late occupant, and

by their affection and domestic skill they made his home a delightful one

to himself and friends. But the chief light of that dwelling is removed, and

there are shadows at Sunnyside that fall darkly upon the visitor who remembers

the sunshine of its former days, for, as his friend Tuckerman wrote on the

day after the funeral,--

"He where fancy were a spell

As lasting as the seems is fair

And made the mountain, stream, and dell,

His own dream-life for ever share:

"He who with England's household's grace,

And with the brave romance of Spain

Tradition's lore and Nature's face,

Imbued his visionary brain:

"Mused in Granada's old arcade

As gushe'd the Moorish fount at noon

With the last minstrel thoughtful stray'd,

To ruin'd shrines beneath the moon:

"And breathed the tenderness and wit

Thus garner'd, in expression pure.

As now his thoughts with humour flit,

And now two pathos wisely lure;

"Who traced with sympathetic hand

Our peerless chieftain's high career

His life that gladden'd all the land,

And blest a hence--is ended here!"

There was a fascination about Mr. Irving that drew every living creature towards him. His personal character, like his writings, was distinguished by extreme modesty, sweetness, and simplicity. "He was never willing to set forth his own pretensions," wrote a friend, after his death; "he was willing to leave to the public the care of his literary reputation. He had no taste for controversy of any sort; his manners were mild, and his conversation, in the society of those with whom he was intimate, was most genial and playful." James Russell Lowell has given the following admirable outline of his character:--

"But allow me to speak what I humbly feet.--

To a true poet-heart add the fun of Dick Steele

Throw in all of Addison, minus the chill:

With the whole of that partnership's stock and good-will,

Mix well, and while stirring, hum o'er as a spell,

The fame old English Gentleman; summer it well

Sweeten just to your own private liking, then strain,

That only the finest and purest remain,

Let it stand out of doors till a soul it receives

From the warm, lazy sun loitering down through green leaves,

And you'll find a choice nature, not wholly deserving

A name either English or Yankee--just Irving. "

I must remember that I am not writing an eulogy of Mr. Irving, but only giving a few outlines with pen and pencil of his late home on the banks of the Hudson. Around that home sweetest memories will ever cluster, and the pilgrim to Sunnyside will rejoice to honour those who made that home so delightful to their idol, and who justly find a place in the sunny recollections of the departed.

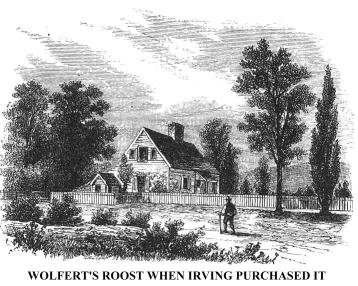

Around that cottage, and the adjacent lands and waters, Irving's

genius has east an atmosphere of romance. The old Dutch house--one of the oldest in all that region--out of

which grew that quaint cottage, was a part of the veritable Wolfert's Roost--the

very dwelling wherein occurred Katrina Van Tassel's memorable quilting frolic,

that terminated so disastrously to Ichabod Crane, in his midnight race with

the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow. There, too, the veracious Dutch historian,

Diedrich Knickerbocker, domiciled while he was deciphering the precious documents

found there, "which, like the lost books of Livy, had baffled the research

of former historians." But its appearance had sadly changed when it was

purchased by Mr. Irving, about thirty years ago, and was by him restored to

the original form of the Roost, which he describes as "a little, old-fashioned

stone mansion, all made up of gable ends, and as full of angles and corners

as an old cocked hat. It is said, in fact," continues Mr. Irving, "to

have been modeled after the cocked hat of Peter the Headstrong, as the Escurial

was modeled after the gridiron of the blessed St. Lawrence." It was built,

the chronicler tells us, by Wolfert Acker, a privy councilor of Peter Stuyvesant,

"a worthy, but ill-starred man, whose aim through life had been to live

in peace and quiet." He sadly failed. "It was his doom, in fact,

to meet a head wind at every turn, and be kept in a constant fume and fret

by the perverseness of mankind. Had he served on a modern jury, he would have

been sure to have eleven unreasonable men opposed to him." He retired

in disgust to this then wilderness, built the gabled house, and "inscribed

over the door (his teeth clenched at the time) his favourite Dutch motto,

'Lust in Rust' (pleasure in quiet). The mansion was thence called Wolfert's

Rust (Wolfert's Rest), but by the uneducated, who did not understand Dutch,

Wolfert's Roost." It passed into the hands of Jacob Van Tassel, a valiant

Dutchman, who espoused the cause of the Republicans. The hostile ships of

the British were often seen in Tappan Bay, in front of the Roost, and Cow

Boys infested the land thereabout. Van Tassel had much trouble: his house

was finally plundered and burnt, and he was carried a prisoner to New York.

When the war was over, he rebuilt the Roost, but in more modest style, as

seen in our sketch. "The Indian spring"--the one brought from Rotterdam--"still

welled up at the bottom of the green bank; and the wild brook, wild as ever,

came babbling down the ravine, and threw itself into the little cove where

of yore the water-guard harboured their whale-boats."

romance. The old Dutch house--one of the oldest in all that region--out of

which grew that quaint cottage, was a part of the veritable Wolfert's Roost--the

very dwelling wherein occurred Katrina Van Tassel's memorable quilting frolic,

that terminated so disastrously to Ichabod Crane, in his midnight race with

the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow. There, too, the veracious Dutch historian,

Diedrich Knickerbocker, domiciled while he was deciphering the precious documents

found there, "which, like the lost books of Livy, had baffled the research

of former historians." But its appearance had sadly changed when it was

purchased by Mr. Irving, about thirty years ago, and was by him restored to

the original form of the Roost, which he describes as "a little, old-fashioned

stone mansion, all made up of gable ends, and as full of angles and corners

as an old cocked hat. It is said, in fact," continues Mr. Irving, "to

have been modeled after the cocked hat of Peter the Headstrong, as the Escurial

was modeled after the gridiron of the blessed St. Lawrence." It was built,

the chronicler tells us, by Wolfert Acker, a privy councilor of Peter Stuyvesant,

"a worthy, but ill-starred man, whose aim through life had been to live

in peace and quiet." He sadly failed. "It was his doom, in fact,

to meet a head wind at every turn, and be kept in a constant fume and fret

by the perverseness of mankind. Had he served on a modern jury, he would have

been sure to have eleven unreasonable men opposed to him." He retired

in disgust to this then wilderness, built the gabled house, and "inscribed

over the door (his teeth clenched at the time) his favourite Dutch motto,

'Lust in Rust' (pleasure in quiet). The mansion was thence called Wolfert's

Rust (Wolfert's Rest), but by the uneducated, who did not understand Dutch,

Wolfert's Roost." It passed into the hands of Jacob Van Tassel, a valiant

Dutchman, who espoused the cause of the Republicans. The hostile ships of

the British were often seen in Tappan Bay, in front of the Roost, and Cow

Boys infested the land thereabout. Van Tassel had much trouble: his house

was finally plundered and burnt, and he was carried a prisoner to New York.

When the war was over, he rebuilt the Roost, but in more modest style, as

seen in our sketch. "The Indian spring"--the one brought from Rotterdam--"still

welled up at the bottom of the green bank; and the wild brook, wild as ever,

came babbling down the ravine, and threw itself into the little cove where

of yore the water-guard harboured their whale-boats."

The "water-guard" was an aquatic corps, in the pay of the revolutionary government, organized to range the waters of the Hudson, and keep watch upon the movements of the British. The Roost, according to the chronicler, was one of the lurking-places of this band, and Van Tassel was one of their best friends. He was, moreover, fond of warring upon his "own hook." He possessed a famous "goose-gun," that would send its shot half-way across Tappan Bay. "When the belligerent feeling was strong upon Jacob," says the chronicler of the Roost, "he would take down his gun, sally forth alone, and prowl along shore, dodging behind rocks and trees, watching for hours together any ship or galley at anchor or becalmed. So sure as a boat approached the shore, bang! went the great goose-gun, sending on board a shower of slugs and buck shot."

On one occasion, Jacob and some fellow bush-fighters peppered a British transport that had run aground. "This," says the chronicler, "was the last of Jacob's triumphs; he fared like some heroic spider that has unwittingly ensnared a hornet, to the utter rain of its web. It was not long after the above exploit that he fell into the hands of the enemy, in the course of one of his forays, and was carried away prisoner to New York. The Roost itself, as a pestilent rebel nest, was marked out for signal punishment. The cock of the Roost being captive, there was none to garrison it but his stout-hearted spouse, his redoubtable sister, Notchie Van Wurmer, and Dinah, a strapping negro wench. An armed vessel came to anchor in front; a boat full of men pulled to shore. The garrison flew to arms, that is to say, to mops, broomsticks, shovels, tongs, and all kinds of domestic weapons, for, unluckily, the great piece of ordnance, the goose-gun, was absent with its owner. Above all, a vigorous defence was made with that most potent of female weapons, the tongue; never did invaded hen-roost make a more vociferous outcry. It was all in vain! The house was sacked and plundered, fire was set to each room, and in a few moments its blaze shed a baleful light over the Tappan Sea. The invaders then pounced upon the blooming Laney Van Tassel, the beauty of the Roost, and endeavoured to bear her off to the boat. But here was the real tug of war. The mother, the aunt, and the strapping negro wench, all flew to the rescue. The struggle continued down to the very water's edge, when a voice from the armed vessel at anchor ordered the spoilers to desist; they relinquished their prize, jumped into their boats, and pulled off, and the heroine of the Roost escaped with a mere rumpling of the feathers."

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.