CHAPTER XXI.

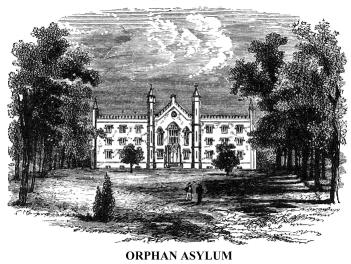

ETWEEN the Bloomingdale Road and the Hudson, and Seventy-third

and Seventy-fourth Streets, is the New York Orphan Asylum, one of the noblest

charities in the land. It is designed for the care and culture of little children

without parents or other protectors.

Here a home and refuge are found for little ones who have been cast upon the cold charities of the world. From one hundred and fifty to two hundred of these children of misfortune are there continually, with their physical, moral, intellectual, and spiritual wants supplied. Their home is a beautiful one. The building is of stone, and the grounds around it, sloping to the river, comprise about fifteen acres. This institution is the child of the "Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children," founded in 1806 by several benevolent ladies, among whom were the sainted Isabella Graham, Mrs. Hamilton, wife of the eminent General Alexander Hamilton, and Mrs. Joanna Bethune, daughter of Mrs. Graham. It is supported by private bequests and annual subscriptions.

There is a similar establishment, called the Leake and Watts Orphan House, situated above the New York Asylum, on One Hundred and Eleventh and One Hundred and Twelfth Streets, between the Ninth and Tenth Avenues. It is surrounded by twenty-six acres of land, owned by the institution. The building, which was first opened for the reception of orphans in 1842, is capable of accommodating about two hundred and fifty children. It was founded by John George Leake, who bequeathed a large sum for the purpose. His executor, John Watts, also made a liberal donation for the same object, and in honour of these benefactors the institution was named.

These comprise the chief public establishments for the unfortunate in the city of New York, near the Hudson river. There are many others in the metropolis, but they do not properly claim a place in these sketches.

Let us here turn towards the interior of the island, drive to the verge of Harlem Plains, and then make a brief tour through the finished portions of the Central Park. Our road will be a little unpleasant a part of the way, for this portion of the island is yet in a state of transition from original roughness to the symmetry produced by art and labour.

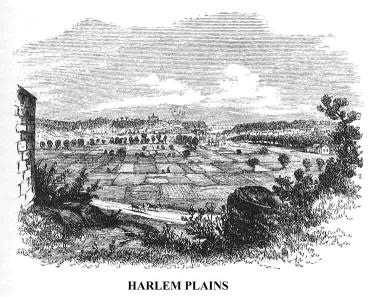

Here,

on the southern verge of the Plains, we will leave our wagon, and climb to

the summit of the rocky bluff, by a winding path up a steep hill covered with

bushes, and take our stand by the side of an old square tower of brick, built

for a redoubt during the war of 1812, and now used as a powder-house. The

view northward, over Harlem Plains, is delightful. From the road at our feet

stretch away numerous "truck" gardens, from which the city draws

vegetable supplies. On the left is seen Manhattanville and a glimpse of the

Palisades beyond the Hudson. In the centre, upon the highest visible point,

is the Convent of the Sacred Heart; and towards the right is the Croton Aqueduct,

or High Bridge, over the Harlem river. The trees on the extreme right mark

the line of the race-course, a mile in length, beginning at Luff's, the great

resort for sportsmen. On this course, the

Here,

on the southern verge of the Plains, we will leave our wagon, and climb to

the summit of the rocky bluff, by a winding path up a steep hill covered with

bushes, and take our stand by the side of an old square tower of brick, built

for a redoubt during the war of 1812, and now used as a powder-house. The

view northward, over Harlem Plains, is delightful. From the road at our feet

stretch away numerous "truck" gardens, from which the city draws

vegetable supplies. On the left is seen Manhattanville and a glimpse of the

Palisades beyond the Hudson. In the centre, upon the highest visible point,

is the Convent of the Sacred Heart; and towards the right is the Croton Aqueduct,

or High Bridge, over the Harlem river. The trees on the extreme right mark

the line of the race-course, a mile in length, beginning at Luff's, the great

resort for sportsmen. On this course, the trotting abilities of fast horses are tried by matches every fine day.

trotting abilities of fast horses are tried by matches every fine day.

In our little view of the Plains and the high ground beyond, is included the theatre of stirring and very important events of the revolution, in the autumn of 1776. Here was fought the battle of Harlem Plains, that saved the American army on Harlem Heights; and yonder, in the distance, was the entrenched camp of the Americans between Manhattanville and Mount Washington, within which occurred most of the sanguinary scenes in the capture of Fort Washington by the British and Hessians.

Our

rocky observatory, more than a hundred feet above tide-water, overlooking

Harlem Plains, is included in the Central Park. Let us descend from it, ride

along the verge of the Plain, and go up east of McGowan's Pass at about. One

Hundred and Ninth Street, where the remains of Forts Fish and Clinton are

yet very prominent. These were built on the site of the fortifications of

the revolution, during the war of 1812. Here we enter among the hundreds of

men employed in fashioning the Central Park. What a chaos is presented! Men,

teams, barrows, blasting, trenching, tunneling, bridging, and every variety

of labour needful in the transforming process. We pick our way over an almost

impassable road among boulders and blasted rocks, to the great artificial

basin of one hundred acres, now nearly completed, which is to be called the

Lake of Man-a-hat-ta. It will really be only an immense tank of Croton

water, for the use of the city. We soon reach the finished portions of the

park, and are delighted with the promises of future grandeur and beauty.

Our

rocky observatory, more than a hundred feet above tide-water, overlooking

Harlem Plains, is included in the Central Park. Let us descend from it, ride

along the verge of the Plain, and go up east of McGowan's Pass at about. One

Hundred and Ninth Street, where the remains of Forts Fish and Clinton are

yet very prominent. These were built on the site of the fortifications of

the revolution, during the war of 1812. Here we enter among the hundreds of

men employed in fashioning the Central Park. What a chaos is presented! Men,

teams, barrows, blasting, trenching, tunneling, bridging, and every variety

of labour needful in the transforming process. We pick our way over an almost

impassable road among boulders and blasted rocks, to the great artificial

basin of one hundred acres, now nearly completed, which is to be called the

Lake of Man-a-hat-ta. It will really be only an immense tank of Croton

water, for the use of the city. We soon reach the finished portions of the

park, and are delighted with the promises of future grandeur and beauty.

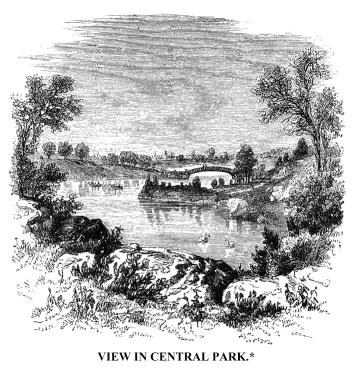

* This is a view of a portion of the Skating-Pond from a high point of the Ramble.

It is impossible, in the brief space allotted to these sketches, to give even a faint appreciative idea of the ultimate appearance of this park, according to the designs of Messrs. Olmstead and Vaux. We may only convey a few hints. The park was suggested by the late A.J. Downing, in 1851, when Kingsland, mayor of the city, gave it his official recommendation. Within a hundred days the Legislature of the State of New York granted the city permission to lay out a park; and in February, 1856, 733 acres of land, in the centre of the island, was in possession of the civic authorities for the purpose. Other purchases for the same end were made, and, finally, the area of the park was extended in the direction of Harlem Plains, so as to include 843 acres. It is more than two and a-half miles long, and half a mile wide, between the Fifth and Eighth Avenues, and Fifty-ninth and One Hundred and Tenth Streets. A great portion of this space was little better than rocky hills and marshy hollows, much of it covered with tangled shrubs and vines. The rocks are chiefly upheavals of gneiss, and the soil is composed mostly of alluvial deposits filled with boulders. Already a wonderful change has been wrought. Many acres have been beautified, and the visitor now has a clear idea of the general character of the park, when completed.

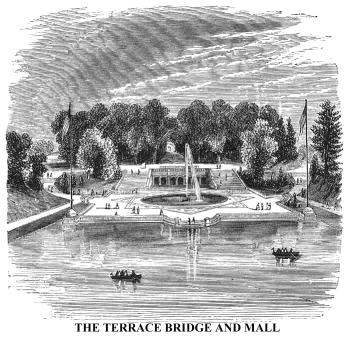

The primary purpose of the park is to provide the best practicable means of healthful recreation for the inhabitants of the city, of all classes. Its chief feature will be a Mall, or broad walk of gravel and grass, 208 feet wide, and a fourth of a mile long, planted with four rows of the magnificent American elm trees, with seats and other requisites for resting and lounging. This, as has been suggested, will be New York's great out-of-doors Hall of Re-union. There will be a carriage-way more than nine miles in length, a bridle-path or equestrian road more than five miles long, and walks for pedestrians full twenty-one miles in length. These will never cross each other. There will also be traffic roads, crossing the park in straight lines from east to west, which will pass through trenches and tunnels, and be seldom seen by the pleasure-seekers in the park.

The whole length of roads and walks will be almost forty miles.

The Croton water tanks already there, and the new one to be made, will jointly cover 150 acres. There are several other smaller bodies of water, in their natural basins. The principal of these is a beautiful, irregular lake, known as the Skating-Pond. Pleasure-boats glide over it in summer, and in winter it is thronged with skaters.* One portion of the Skating-Pond is devoted exclusively to the gentler sex. These, of nearly all ages and conditions, throng the ice whenever the skating is good.

* The New York Spirit of the Times, referring to this lake, said:--"From the commencement of the skating to the 24th day of February (1861) was sixty-three days; there was skating on forty-five days, and no skating on eighteen days. Of visitors to the pond, the least number on any one day was one hundred; the largest number on one day (Christmas) estimated at 100,000; aggregate number during the season, 540,000; average number on skating days, 12,000."

Open spaces are to be left for military parades, and large plats of turf for games, such as ball and cricket, will be laid down--about twenty acres for the former, and ten for the latter; and it is intended to have a beautiful meadow in the centre of the park.

There will be arches of cut stone, and numerous bridges of iron and stone (the latter handsomely ornamented and fashioned in the most costly style), spanning the traffic-roads, ravines, and ponds. One of the most remarkable of these, forming a central architectural feature, is the Terrace Bridge, at the north end of the Mall, already approaching completion. This bridge covers a broad arcade, where, in alternate niches, will be statues and fountains. Below will be a platform, 170 feet wide, extending to the border of the Skating-Pond. It will embrace a spacious basin, with a fine fountain jet in its centre. This structure will be composed of exquisitely wrought light brown freestone, and granite.

Such is a general idea of the park, the construction of which was begun at the beginning of 1858; it is expected to be completed in 1864--a period of only about six years. The entire cost will not fall much short of 12,000,000 dollars. As many as four thousand men and several hundred horses have been at work upon it at one time.*

* This brief description was written, and the accompanying sketches were made, in 1861. The great work of fashioning this Park, leaving Nature, in the growth of trees and shrubbery, to enrich and beautify it, is now (1866) nearly completed.

From the Central Park--where beauty and symmetry in the hands of Nature and Art already performed noble aesthetic service for the citizens of New York--let us ride to "Jones's Woods," on the eastern borders of the island, where, until recently, the silence of the country forest might have been enjoyed almost within sound of the hum of the busy town.

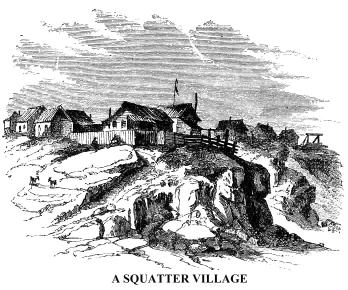

But here, as everywhere else, on the upper part of Manhattan

Island, the early footprints in the march of  improvement

are seen. As we leave the beautiful arrangement of the park, the eye immediately

encounters scenes of perfect chaos, where animated and unanimated nature combine

in making pictures upon memory, never to be forgotten. The opening and grading

of new streets produce many rugged bluffs of earth and rock; and upon these,

whole villages of squatters, who are chiefly Irish, may be seen. These inhabitants

have the most supreme disregard for law or custom in planting their dwellings.

To them the land seems to "lie out of doors," without visible owners,

bare and unproductive. Without inquiry they take full possession, erect cheap

cabins upon the "public domains," and exercise "squatter sovereignty"

in an eminent degree, until some, innovating owner disturbs their repose and

their title, by undermining their castles--for in New York, as in England,

"every man's house is his castle."

improvement

are seen. As we leave the beautiful arrangement of the park, the eye immediately

encounters scenes of perfect chaos, where animated and unanimated nature combine

in making pictures upon memory, never to be forgotten. The opening and grading

of new streets produce many rugged bluffs of earth and rock; and upon these,

whole villages of squatters, who are chiefly Irish, may be seen. These inhabitants

have the most supreme disregard for law or custom in planting their dwellings.

To them the land seems to "lie out of doors," without visible owners,

bare and unproductive. Without inquiry they take full possession, erect cheap

cabins upon the "public domains," and exercise "squatter sovereignty"

in an eminent degree, until some, innovating owner disturbs their repose and

their title, by undermining their castles--for in New York, as in England,

"every man's house is his castle."  These

form the advanced guard of the growing metropolis; and so eccentric is Fortune

in the distribution of her favours in this land of general equality, that

a dweller in these "suburban cottages," where swine and goats are

seen instead of deer and blood-cattle, may, not many years in the future,

occupy a palace upon Central Park--perhaps, upon the very spot where he now

uses a pig for a pillow, and breakfasts upon the milk of she-goats. In a superb

mansion of his own, within an arrow's flight of Madison Park, lived a middle-aged

man in 1861, whose childhood was thus spent among the former squatters in

that quarter.

These

form the advanced guard of the growing metropolis; and so eccentric is Fortune

in the distribution of her favours in this land of general equality, that

a dweller in these "suburban cottages," where swine and goats are

seen instead of deer and blood-cattle, may, not many years in the future,

occupy a palace upon Central Park--perhaps, upon the very spot where he now

uses a pig for a pillow, and breakfasts upon the milk of she-goats. In a superb

mansion of his own, within an arrow's flight of Madison Park, lived a middle-aged

man in 1861, whose childhood was thus spent among the former squatters in

that quarter.

"Jones's Woods," formerly occupying the space between

the Third Avenue and the East River, and Sixtieth and Eightieth Streets, are

rapidly disappearing. Streets have been cut through them, clearings for buildings

have been

made, and that splendid grove of old forest trees a few years ago, has been

changed to clumps, giving shade to large numbers of pleasure-seekers during

the hot months of summer, and the delightful weeks of early autumn. There,

in profound retirement, in an elegant mansion on the bank of the East River,

lived David Provoost, better known to the inhabitants of New York--more than

a hundred years ago-- as "Ready-money Provoost." This title he acquired

because of the sudden increase of his wealth by the illicit trade in which

some of the colonists were then engaged, in spite of the vigilance of the

mother country. He married the widow of James Alexander, and mother of Lord

Stirling, an eminent American officer in the old war for independence. In

a family vault, cut in a rocky knoll at the request of his first wife, he

was buried, and his remains were removed only when it was evident that they

would no longer be respected by the Commissioner of Streets. It is now a dilapidated

ruin near the foot of Seventy-first Street. The marble slab that he placed

over the vault in memory of his wife (and which commemorates him also) lies

neglected, over the broken walls.* The fingers of destruction are busy there.

have been

made, and that splendid grove of old forest trees a few years ago, has been

changed to clumps, giving shade to large numbers of pleasure-seekers during

the hot months of summer, and the delightful weeks of early autumn. There,

in profound retirement, in an elegant mansion on the bank of the East River,

lived David Provoost, better known to the inhabitants of New York--more than

a hundred years ago-- as "Ready-money Provoost." This title he acquired

because of the sudden increase of his wealth by the illicit trade in which

some of the colonists were then engaged, in spite of the vigilance of the

mother country. He married the widow of James Alexander, and mother of Lord

Stirling, an eminent American officer in the old war for independence. In

a family vault, cut in a rocky knoll at the request of his first wife, he

was buried, and his remains were removed only when it was evident that they

would no longer be respected by the Commissioner of Streets. It is now a dilapidated

ruin near the foot of Seventy-first Street. The marble slab that he placed

over the vault in memory of his wife (and which commemorates him also) lies

neglected, over the broken walls.* The fingers of destruction are busy there.

* The slab bears the following inscription: "JOANNAH RYNDERS, who was the most loving wife of David Provoost. It was her will to be interred in this hill. Obitus December, 1749, aged 43 years." "Sucured to the memo y of DAVID PROVOOST, who died Oct. 19th, 1781, aged 90 years."

The old Provoost mansion is gone, and with it has departed the quiet of the scene. Near its site, large assemblages of people listen to music, hold festivals, dance, partake of refreshments of almost every kind, and fill the air with the voices of mirth. The Germans, who love the open air, go thither in large numbers; and tents wherein lager bier is sold, form conspicuous objects in that still half sylvan retreat. There Blondin walked his rope at fearful heights, among the tall tulip trees; and there, in autumn, the young people may yet gather nuts from the hickory trees, and gorgeous leaves from the birch, the chestnut, and the maple. But half a decade will not pass, before "Jones's Woods" will be among the things that have passed away.

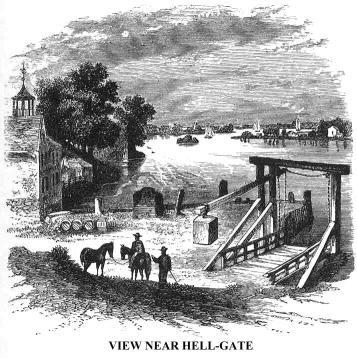

A little beyond this, at Eighty-sixth Street, a road leads down to Astoria Ferry, on the East River, a short distance below the mouth of the Harlem River. This is a great thoroughfare, as it leads to many pleasant residences on Long Island, and the delightful roads in that vicinity. From this ferry may be obtained a fine view of Mill Rock in the East River, Hallett's Point, the village of Astoria, and other places of interest in the vicinity of a dangerous whirlpool, named by the Dutch Helle-gat (Hell-hole), now called Hell-gate. It is no longer dangerous to navigators, the sunken rocks which formed the whirlpool having been removed in 1852, by submarine blasting, in which electricity was employed.

This

is an interesting historic locality. Here the town records of Newport, Rhode

Island, carried away by Sir Henry Clinton, were submerged in 1779, when the

British vessel that bore them was wrecked near the vortex. They were recovered.

Here, during the revolution, the British frigate Huzzar was wrecked, and sunk

in deep water, having on board, it was believed, a large amount of specie,

destined for the use of the British troops in America. On Mill Rock, a strong

block-house was erected during the war of 1812; and on Hallett's Point, a

military work called Fort Stevens was constructed at the same time.

This

is an interesting historic locality. Here the town records of Newport, Rhode

Island, carried away by Sir Henry Clinton, were submerged in 1779, when the

British vessel that bore them was wrecked near the vortex. They were recovered.

Here, during the revolution, the British frigate Huzzar was wrecked, and sunk

in deep water, having on board, it was believed, a large amount of specie,

destined for the use of the British troops in America. On Mill Rock, a strong

block-house was erected during the war of 1812; and on Hallett's Point, a

military work called Fort Stevens was constructed at the same time.

Near Hell-gate the Harlem River enters the East River, and not far distant are Ward's and Randall's Islands. These belong to the corporation of New York. The former contains a spacious emigrants' hospital, and the latter nursery schools for poor children, and a penal house of refuge for juvenile delinquents. This is a delightful portion of the East River, and here the lover of sport may find good fishing at proper seasons.

Ward's Island contains about 200 acres, and lies in the East River, from One Hundred and First to One Hundred and Fifteenth Streets inclusive. The Indians called it Ten-ken-as. It was purchased from them by First Director Van Twilles, in 1637. A portion of the island is a potter's field, where about 2,500 of the poor and strangers are buried annually. The island is supplied with Croton water. A ferry connects it with the city at One Hundred and Sixth Street. Randall's Island, nearly north from Ward's, close by the Westchester shore, was the residence of Jonathan Randall for almost fifty years; he purchased it in 1754. It has been called, at different times, Little Barn Island, Belle Isle, Talbot's Island, and Montressor's Island. The city purchased it, in 1835, for 50,000 dollars. The House of Refuge is on the southern part of the island, opposite One Hundred and Seventeenth Street. There youthful criminals are kept free from the contaminating influence of old offenders, are taught useful trades, and are continually subjected to reforming influences. Good homes are furnished them when they leave the institution, and in this way the children of depraved parents who have entered upon a career of crime, have their feet set in the paths of virtue, usefulness, and honour.

Near the southern border of "Jones's Woods" is "The Coloured Home," where the indigent, sick, and infirm of African blood have their physical, moral, and religious wants supplied. It is managed by an association of women, and is sustained by the willing hands of the benevolent.

A little farther south, on the high bank of the East River, at Fifty-first Street, is the ancient family mansion of a branch of the Beekman family, whose ancestor accompanied Governor Stuyvesant to New Amsterdam, now New York. There General Howe made his head-quarters after the battle on Long Island and his invasion of New York, in 1776; and there he was made Sir William Howe, because of those events, by knightly ceremonies performed by brother officers, at the command of the king. Captain Nathan Hale, the spy, whose case and Major André's have been compared, was brought before General Howe at this place soon after his arrest. He was confined during the night in the conservatory, and the next morning, without even the form of a trial, was handed over to Cunningham, the inhuman provost marshal, who hanged him upon an apple-tree, under circumstances of peculiar cruelty. The act was intended to strike the minds of the Americans with terror; it only served to exasperate and strengthen them.*

* Nathan Hale was an exemplary young man, of a good Connecticut family. Washington was anxious to ascertain the exact position and condition of the British army on Long Island, and Hale volunteered to obtain it. He was arrested, and consigned to Cunningham for execution. He was refused the services of a clergyman and use of a Bible, and letters that he wrote during the night to his mother and sisters were destroyed by the inhuman marshal. His last words were,--"I only regret that I have but one life to give to my country."

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.