CHAPTER III

THE

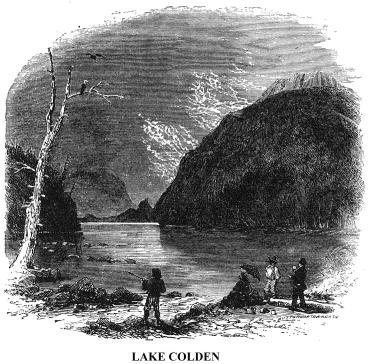

cold increased every moment as the sun declined, and, after remaining on the

summit of Tahawus only an hour, we descended to the Opalescent River, where

we encamped for the night. Toward morning there was a rain-shower, and the

water came trickling upon us through the light bark roof of our "camp."

But the clouds broke at sunrise, and, excepting a copious shower of small

hail, and one or two of light rain, we had pleasant weather the remainder

of the day. We descended the Opalescent in its rocky bed, as we went up, and

at noon dined on the margin of Lake Colden, just after a slight shower had

passed by.

THE

cold increased every moment as the sun declined, and, after remaining on the

summit of Tahawus only an hour, we descended to the Opalescent River, where

we encamped for the night. Toward morning there was a rain-shower, and the

water came trickling upon us through the light bark roof of our "camp."

But the clouds broke at sunrise, and, excepting a copious shower of small

hail, and one or two of light rain, we had pleasant weather the remainder

of the day. We descended the Opalescent in its rocky bed, as we went up, and

at noon dined on the margin of Lake Colden, just after a slight shower had

passed by.

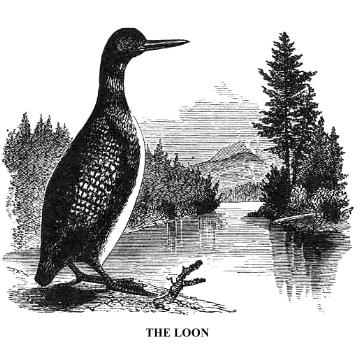

We were now at an elevation of almost three thousand feet above tide water. In lakes Colden and Avalanche, which lie close to each other, there are no fishes. Only lizards and leeches occupy their cold waters. All is silent and solitary there. The bald eagle sweeps over them occasionally, or perches upon a lofty pine, but the mournful voice of the Great Loon, or Diver (Colymbus glacialis), heard over all the waters of northern New York and Canada, never awakens the echoes of these solitary lakes.* These waters lie in a high basin between the Mount Colden and Mount M'Intyre ranges, and have experienced great changes. Avalanche Lake, evidently once a part of Lake Colden, is about eighty feet higher than the latter, and more than two miles from it. They have been separated by, perhaps, a series of avalanches, or mountain slides, which still occur in that region. From the top of Tahawus we saw the white glare of several, striping the sides of mountain cones.

* The water view in the picture of the Loon is a scene on Harris's Lake, with Goodenow Mountain in the distance.

At three o'clock we reached our camp at Calamity Pond, and just before sunset emerged from the forest into the open fields near Adirondack village, where we regaled ourselves with the bountiful fruitage of the raspberry shrub. At Mr. Hunter's we found kind and generous entertainment, and at an early hour the next morning we started for the great Indian Pass, four miles distant.

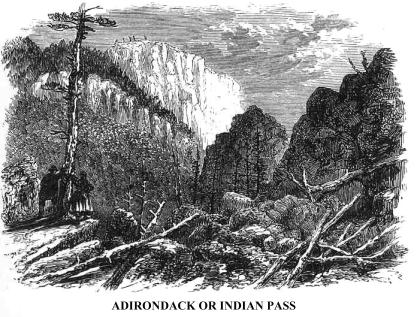

Half

a mile from Henderson Lake we crossed its outlet upon a picturesque bridge,

and following a causeway another half a mile through a clearing, we penetrated

the forest, and struck one of the chief branches of the Upper Hudson, that

comes from the rocky chasms of that Pass. Our journey was much more difficult

than to Tahawus. The undergrowth of the forest was more dense, and trees more

frequently lay athwart the dim trail. We crossed the stream several times,

and, as we ascended, the valley narrowed until we entered the rocky gorge

between the steep slopes of Mount M'Intyre and the cliffs of Wall-face Mountain.

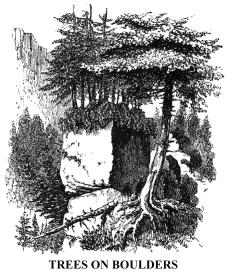

There we encountered enormous masses of rocks, some worn by the abrasion of

the elements, some angular, some bare, and some covered with moss, and many

of them bearing large trees, whose roots, clasping them on all sides, strike

into the earth for sustenance. One of the masses presented a singular appearance;

it is of cubic form, its summit full thirty feet from its base, and upon it

was quite a grove of hemlock and cedar trees. Around and partly under this

and others lying loosely,

Half

a mile from Henderson Lake we crossed its outlet upon a picturesque bridge,

and following a causeway another half a mile through a clearing, we penetrated

the forest, and struck one of the chief branches of the Upper Hudson, that

comes from the rocky chasms of that Pass. Our journey was much more difficult

than to Tahawus. The undergrowth of the forest was more dense, and trees more

frequently lay athwart the dim trail. We crossed the stream several times,

and, as we ascended, the valley narrowed until we entered the rocky gorge

between the steep slopes of Mount M'Intyre and the cliffs of Wall-face Mountain.

There we encountered enormous masses of rocks, some worn by the abrasion of

the elements, some angular, some bare, and some covered with moss, and many

of them bearing large trees, whose roots, clasping them on all sides, strike

into the earth for sustenance. One of the masses presented a singular appearance;

it is of cubic form, its summit full thirty feet from its base, and upon it

was quite a grove of hemlock and cedar trees. Around and partly under this

and others lying loosely,  apparently

kept from rolling by roots and vines, we were compelled to clamber a long

distance, when we reached a point more than one hundred feet above the bottom

of the gorge, where we could see the famous pass in all its wild grandeur.

Before us arose a perpendicular cliff, nearly twelve hundred feet from base

to summit, as raw in appearance as if cleft only yesterday. Above us sloped

M'Intyre, still more lefty than the cliff of Wall-face, and in the gorge lay

huge piles of rock, chaotic in position, grand in dimensions, and awful in

general aspect. They appear to have been cast in there by some terrible convulsion

not very remote. Within the memory of Sabattis, this region has been shaken

by an earthquake, and no doubt its power, and the lightning, and the frost,

have hurled these masses from that impending cliff. Through these the waters

of this branch of the Hudson, bubbling from a spring not far distant (close

by a fountain of the Au Sable), find their way. Here the head-waters of this

river commingle in the Spring season, and when they separate they find their

way to the Atlantic Ocean, as we have observed, at points a thousand miles

apart. The margin of the stream is too rugged and cavernous in the Pass for

human footsteps to follow.

apparently

kept from rolling by roots and vines, we were compelled to clamber a long

distance, when we reached a point more than one hundred feet above the bottom

of the gorge, where we could see the famous pass in all its wild grandeur.

Before us arose a perpendicular cliff, nearly twelve hundred feet from base

to summit, as raw in appearance as if cleft only yesterday. Above us sloped

M'Intyre, still more lefty than the cliff of Wall-face, and in the gorge lay

huge piles of rock, chaotic in position, grand in dimensions, and awful in

general aspect. They appear to have been cast in there by some terrible convulsion

not very remote. Within the memory of Sabattis, this region has been shaken

by an earthquake, and no doubt its power, and the lightning, and the frost,

have hurled these masses from that impending cliff. Through these the waters

of this branch of the Hudson, bubbling from a spring not far distant (close

by a fountain of the Au Sable), find their way. Here the head-waters of this

river commingle in the Spring season, and when they separate they find their

way to the Atlantic Ocean, as we have observed, at points a thousand miles

apart. The margin of the stream is too rugged and cavernous in the Pass for

human footsteps to follow.

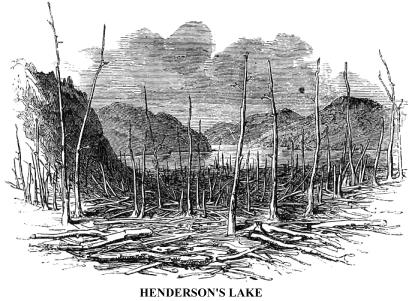

Just

at the lower entrance to the gorge, on the margin of the little brook, we

dined, and then retraced our steps to the village, stopping on the way to

view the dreary swamp at the head of Henderson Lake, where the Hudson, flowing

from the Pass, enters it. Water, and not fire, has blasted the trees, and

their erect stems and prostrate branches, white and ghost-like in appearance,

make a tangled covering over many acres.

Just

at the lower entrance to the gorge, on the margin of the little brook, we

dined, and then retraced our steps to the village, stopping on the way to

view the dreary swamp at the head of Henderson Lake, where the Hudson, flowing

from the Pass, enters it. Water, and not fire, has blasted the trees, and

their erect stems and prostrate branches, white and ghost-like in appearance,

make a tangled covering over many acres.

That night we slept soundly again at Mr. Hunter's, and in the

morning left in a waggon for the valley of the Scarron. During the past four

days we had traveled thirty miles on foot in the tangled forest, camped out

two nights, and seen some of nature's wildest and grandest lineaments. These

mountain and lake districts, which form the wilderness of northern New York,

give to the tourist most exquisite sensations, and the physical system appears

to take in health at every pore. Invalids go in with hardly strength enough

to reach some quiet log-house in a clearing, and come out with strong quick

pulse and elastic muscles. Every year the number of tourists and sportsmen

who go there rapidly increases, and  women

begin to find more pleasure and health in that wilderness than at fashionable

watering-places. No wild country in the world can offer more solid attractions

to these who desire to spend a few weeks of leisure away from the haunts of

men. Pure air and water, and game in abundance, may there be found, while

in all that region not a venomous reptile or poisonous plant may be seen,

and the beasts of prey are too few and shy to cause the least alarm to the

most timid. The climate is delightful, and there are fertile valleys among

those rugged hills that will yet smile in beauty under the cultivator's hand.

It has been called by the uninformed the "Siberia of New York;"

it may more properly be called the "Switzerland of the United States."

women

begin to find more pleasure and health in that wilderness than at fashionable

watering-places. No wild country in the world can offer more solid attractions

to these who desire to spend a few weeks of leisure away from the haunts of

men. Pure air and water, and game in abundance, may there be found, while

in all that region not a venomous reptile or poisonous plant may be seen,

and the beasts of prey are too few and shy to cause the least alarm to the

most timid. The climate is delightful, and there are fertile valleys among

those rugged hills that will yet smile in beauty under the cultivator's hand.

It has been called by the uninformed the "Siberia of New York;"

it may more properly be called the "Switzerland of the United States."

The wind came from among the mountains in fitful gusts, thick

mists were sweeping around the peaks and through the gorges, and there were

frequent dashes of rain, sometimes falling like showers of gold, in the sunlight

that gleamed through the broken clouds, on the morning when we left Adirondack

village. We had hired a strong waggon, with three spring seats, and a team

of experienced horses, to convey us from the heart of the wilderness to the

Scarron valley, thirty miles distant, and after breakfast we left the kind

family of Mr. Hunter, accompanied by  Sabattis

and Preston, who rode with us most of the way for ten miles, in the direction

of their homes. Our driver was the owner of the team--a careful, intelligent,

good-natured man, who lived near Tahawus, at the foot of Sandford Lake. But

in all our experience in traveling, we never endured such a journey. The highway,

for at least twenty-four of the thirty miles, is what is technically called

corduroy--a sort of corrugated stripe of logs ten feet wide, laid through

the woods, and dignified with the title of "The State road." It

gives to a waggon the jolting motion of the "dyspeptic chair," and

in that way we were "exercised" all day long, except when dining

at the Tahawus House, on some wild pigeons shot by Sabattis on the way. That

inn was upon the road, near the site of Tahawus village, at the foot of Sandford

Lake, and was a half-way house between Long Lake and Root's Inn in the Scarron

valley, toward which we were traveling. There we parted with our excellent

guides, after giving them a sincere assurance that we should recommend all

tourists and hunters, who may visit the head waters of the Hudson, to procure

their services, if possible.

Sabattis

and Preston, who rode with us most of the way for ten miles, in the direction

of their homes. Our driver was the owner of the team--a careful, intelligent,

good-natured man, who lived near Tahawus, at the foot of Sandford Lake. But

in all our experience in traveling, we never endured such a journey. The highway,

for at least twenty-four of the thirty miles, is what is technically called

corduroy--a sort of corrugated stripe of logs ten feet wide, laid through

the woods, and dignified with the title of "The State road." It

gives to a waggon the jolting motion of the "dyspeptic chair," and

in that way we were "exercised" all day long, except when dining

at the Tahawus House, on some wild pigeons shot by Sabattis on the way. That

inn was upon the road, near the site of Tahawus village, at the foot of Sandford

Lake, and was a half-way house between Long Lake and Root's Inn in the Scarron

valley, toward which we were traveling. There we parted with our excellent

guides, after giving them a sincere assurance that we should recommend all

tourists and hunters, who may visit the head waters of the Hudson, to procure

their services, if possible.

About a mile on our way from the Tahawus House, we came to

the dwelling and farm of John Cheney, the  oldest

and most famous hunter and guide in all that region. He then seldom went far

into the woods, for he was beginning to feel the effects of age and a laborious

life. We called to pay our respects to one so widely known, and yet so isolated,

and were disappointed. He was away on a short hunting excursion, for he loves

the forest and the chase with all the enthusiasm of his young manhood. He

is a slightly-built man, about sixty years of age. He was the guide for the

scientific corps, who made a geological reconnaissance of that region many

years before, and for a quarter of a century he had there battled the elements

and the beasts with a strong arm and unflinching will. Many of the tales of

his experience are full of the wildest romance, and we hoped to hear the narrative

of some adventure from his own lips.

oldest

and most famous hunter and guide in all that region. He then seldom went far

into the woods, for he was beginning to feel the effects of age and a laborious

life. We called to pay our respects to one so widely known, and yet so isolated,

and were disappointed. He was away on a short hunting excursion, for he loves

the forest and the chase with all the enthusiasm of his young manhood. He

is a slightly-built man, about sixty years of age. He was the guide for the

scientific corps, who made a geological reconnaissance of that region many

years before, and for a quarter of a century he had there battled the elements

and the beasts with a strong arm and unflinching will. Many of the tales of

his experience are full of the wildest romance, and we hoped to hear the narrative

of some adventure from his own lips.

For many years John carried no other weapons than a huge jack-knife and a pistol. One of the most stirring of his thousand adventures in the woods is connected with the history of that pistol. It has been related by an acquaintance of the writer, a man of rare genius, and who, for many years, has been an inmate of an asylum for the insane, in a neighbouring State. John Cheney was his guide more than twenty years before our visit. The time of the adventure alluded to was winter, and the snow lay four feet deep in the woods. John went out upon snow-shoes, with his rifle and dogs. He wandered far from the settlement, and made his bed at night in the deep snow. One morning he arose to examine his traps, near which he would lie encamped for weeks in complete solitude. When hovering around one of them, he discovered a famished wolf, who, unappalled by the hunter, retired only a few steps, and then, turning round, stood watching his movements. "I ought, by rights," said John, "to have waited for my two dogs, who could not have been far off, but the creature looked so sassy, standing there, that though I had not a bullet to spare, I could not help letting into him with my rifle." John missed his aim, and the animal gave a spring, as he was in the act of firing, and turned instantly upon him before he could reload his piece. So effective was the unexpected attack of the wolf, that his fore-paws were upon Cheney's snow-shoes before he could reload his piece rally for the fight. The forester became entangled in the deep drift, and sank upon his back, keeping the wolf at bay only by striking at him with his clubbed rifle. The stock of it was broken into pieces in a few moments, and it would have fared ill with the stark woodsman if the wolf, instead of making at his enemy's throat when he had him thus at disadvantage, had not, with blind fury, seized the barrel of the gun in his jaws. Still the fight was unequal, as John, half buried in the snow, could make use of but one of his hands. He shouted to his dogs, but one of them only, a young, untrained hound, made his appearance. Emerging from a thicket he caught sight of his master, lying apparently at the mercy of the ravenous beast, uttered a yell of fear, and fled howling to the woods again. "Had I had one shot left," said Cheney, "I would have given it to that dog instead of dispatching the wolf with it." In the exasperation of the moment John might have extended his contempt to the whole canine race, if a stauncher friend had not, at the moment, interposed to vindicate their character for courage and fidelity. All this had passed in a moment; the wolf was still grinding the iron gun-barrel in his teeth--he had even once wrenched it from the hand of the hunter--when, dashing like a thunderbolt between the combatants, the other hound sprang over his master's body, and seized the wolf by the throat. "There was no let go about that dog when he once took hold," said John. "If the barrel had been red hot the wolf couldn't have dropped it quicker, and it would have done you good, I tell you, to see that old dog drag the creature's head down in the snow, while I, just at my leisure, drove the iron into his skull. One good, fair blow, though, with a heavy rifle barrel, on the back of the head, finished him. The fellow gave a kind o' quiver, stretched out his hind legs, and then he was done for. I had the rifle stocked afterwards, but she would never shoot straight since that fight, so I got me this pistol, which, being light and handy, enables me more conveniently to carry an axe upon my long tramps, and make myself comfortable in the woods."

Many a deer has John since killed with that pistol. "It is curious," said the narrator, "to see him draw it from the left pocket of his grey shooting-jacket, and bring down a partridge. I have myself witnessed several of his successful shots with this unpretending shooting-iron, and once saw him knock the feathers from a wild duck at fifty yards."

Most

of our journey toward the Scarron was quite easy for the horses, for we were

descending the great Champlain slope. The roughness of the road compelled

us to allow the team to walk most of the way. The country was exceedingly

picturesque. For miles our track lay through the solitary forest, its silence

disturbed only by the sound of a mountain brook, or the voices of the wind

among the hills. The winding road was closely hemmed by trees and shrubs,

and sentineled by lofty pines, and birches, and tamaracks, many of them dead,

and ready to fall at the touch of the next strong wind. Miles apart were the

rude cabins of the settlers, until we came out upon a high, rolling valley,

surrounded by a magnificent amphitheatre of hills. Through that valley, from

a little lake toward the sources of the Au Sable, flows the cold and rapid

Boreas River, one of the chief tributaries of the Upper Hudson. The view was

now grand: all around us stood the great hills, wooded to their summits, and

over-looking deep valleys, wherein the primeval forest had never been touched

by axe or fire; and on the right, through tall trees, we had glimpses of an

irregular little lake, called Cheney Pond. For three or four miles after passing

the Boreas we went over a most dreary "clearing," dotted with blackened

stumps and boulders as thick as hail, a cold north-west wind driving at our

backs. In the midst of it is Wolf Pond, a dark water fringed with a tangled

growth of alders, shrubs, and creepers, and made doubly gloomy by hundreds

of dead trees, that shoot up from the chapparal.

Most

of our journey toward the Scarron was quite easy for the horses, for we were

descending the great Champlain slope. The roughness of the road compelled

us to allow the team to walk most of the way. The country was exceedingly

picturesque. For miles our track lay through the solitary forest, its silence

disturbed only by the sound of a mountain brook, or the voices of the wind

among the hills. The winding road was closely hemmed by trees and shrubs,

and sentineled by lofty pines, and birches, and tamaracks, many of them dead,

and ready to fall at the touch of the next strong wind. Miles apart were the

rude cabins of the settlers, until we came out upon a high, rolling valley,

surrounded by a magnificent amphitheatre of hills. Through that valley, from

a little lake toward the sources of the Au Sable, flows the cold and rapid

Boreas River, one of the chief tributaries of the Upper Hudson. The view was

now grand: all around us stood the great hills, wooded to their summits, and

over-looking deep valleys, wherein the primeval forest had never been touched

by axe or fire; and on the right, through tall trees, we had glimpses of an

irregular little lake, called Cheney Pond. For three or four miles after passing

the Boreas we went over a most dreary "clearing," dotted with blackened

stumps and boulders as thick as hail, a cold north-west wind driving at our

backs. In the midst of it is Wolf Pond, a dark water fringed with a tangled

growth of alders, shrubs, and creepers, and made doubly gloomy by hundreds

of dead trees, that shoot up from the chapparal.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.