CHAPTER FOUR, PART TWO

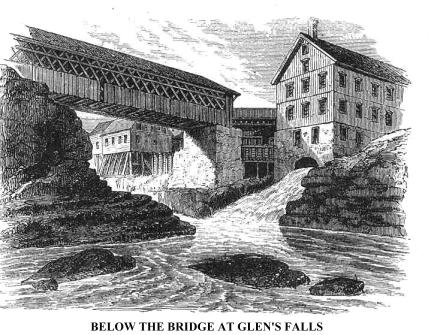

Glen's

Falls village is beautifully situated upon a plain on the north side of the

river, and occupies a conspicuous place in the trade and travel of that section

of the State.* . The water-power there is very great, and is used extensively

for flouring and lumber mills. The surplus water supplies a navigable feeder

to the Champlain Canal, that connects Lake Champlain with the Hudson. There

are also several mills for slabbing the fine black marble of that locality

for the construction of chimney-pieces, and for other uses. These various

mills mar the natural beauty of the scene, but their uncouth and irregular

forms give picturesqueness to the view. The bridge crosses just at the foot

of the falls. It rests upon abutments of strong masonry at each end, and a

pier in the middle, which is seated upon the caverned rock, just mentioned,

which was once in the bed of the stream. The channel on the southern side

has been closed by an abutment, and one of the chambers of the cavern, made

memorable by Cooper, is completely shut. When we were there, huge logs nearly

filled the upper entrance to it. Below the bridge the shores are black marble,

beautifully stratified, perpendicular, and, in some places, seventy feet in

height. Between these walls the water runs with a swift current for nearly

a mile, and finally, at Sandy Hill, three miles below, is broken into rapids.

Glen's

Falls village is beautifully situated upon a plain on the north side of the

river, and occupies a conspicuous place in the trade and travel of that section

of the State.* . The water-power there is very great, and is used extensively

for flouring and lumber mills. The surplus water supplies a navigable feeder

to the Champlain Canal, that connects Lake Champlain with the Hudson. There

are also several mills for slabbing the fine black marble of that locality

for the construction of chimney-pieces, and for other uses. These various

mills mar the natural beauty of the scene, but their uncouth and irregular

forms give picturesqueness to the view. The bridge crosses just at the foot

of the falls. It rests upon abutments of strong masonry at each end, and a

pier in the middle, which is seated upon the caverned rock, just mentioned,

which was once in the bed of the stream. The channel on the southern side

has been closed by an abutment, and one of the chambers of the cavern, made

memorable by Cooper, is completely shut. When we were there, huge logs nearly

filled the upper entrance to it. Below the bridge the shores are black marble,

beautifully stratified, perpendicular, and, in some places, seventy feet in

height. Between these walls the water runs with a swift current for nearly

a mile, and finally, at Sandy Hill, three miles below, is broken into rapids.

* Not long after our visit here mentioned, a greater portion of the village was destroyed by fire, but it was soon rebuilt.

At Sandy Hill the Hudson makes a magnificent sweep, in a curve, when changing its course from an easterly to a southerly direction; and a little below that village it is broken into wild cascades, which have been named Baker's Falls. Sandy Hill, like the borough of Glen's Falls, stands upon a high plain, and is a very beautiful village, of about thirteen hundred inhabitants. In its centre is a shaded green, which tradition points to as the spot where a tragedy was enacted more than a century ago, some incidents of which remind us of the romantic but truthful story of Captain Smith and Pocahantas, in Virginia. The time of the tragedy was during the old French war, and the chief actor was a young Albanian, son of Sybrant Quackenboss, one of the sturdy Dutch burghers of that old city. The young man was betrothed to a maiden of the same city; the marriage day was fixed, and preparations for the nuptials were nearly completed, when he was impressed into the military service as a waggoner, and required to convey a load of provisions from Albany to Fort William Henry, at the head of Lake George. He had passed Fort Edward with an escort of sixteen men, under Lieutenant McGinnis, of New Hampshire, and was making his way through the gloomy forest at the bend of the Hudson, when they were attacked, overpowered, and disarmed by a party of French Indians, under the famous partisan Marin. The prisoners were taken to the trunk of a fallen tree, and seated upon it in a row. The captors then started toward Fort Edward, leaving the helpless captives strongly bound with green withes, in charge of two or three stalwart warriors, and their squares, or wives. In the course of an hour the party returned. Young Quackenboss was seated at one end of the log, and Lieutenant McGinnis next him. The savages held a brief consultation, and then one of them, with a glittering tomahawk, went to the end of the log opposite Quackenboss, and deliberately sank his weapon in the brain of the nearest soldier. He fell dead upon the ground. The second shared a like fate, then a third, and so on until all were slain but McGinnis and Quackenboss. The tomahawk was raised to cleave the skull of the former, when he threw himself suddenly backward from the log, and attempted to break his bonds. In an instant a dozen tomahawks gleamed over his head. For a while he defended himself with his heels, lying upon his back, but after being severely hewn with their hatchets, he was killed by a blow. Quackenboss alone remained of the seventeen. As the fatal steel was about to fall upon his head, the arm of the savage executioner was arrested by a squaw, who exclaimed, "You shan't kill him! He's no fighter! He's my dog!" He was spared and unbound, and, staggering under a pack of plunder almost too heavy for him to sustain, he was marched towards Canada, as a prisoner, the Indians bearing the scalps of his murdered fellow captives as trophies. They went down Lake Champlain in canoes, and at the first Indian village, after reaching its foot, he was compelled to run the gauntlet between rows of savage men armed with clubs. In this terrible ordeal he was severely wounded. His Indian mistress then took him to her wigwam, bound up his wounds, and carefully nursed him until he was fully recovered. The Governor of Canada ransomed him, took him to Montreal, and there he was employed as a weaver. He obtained the governor's permission to write to his parents to inform them of his fate. The letter was carried by an Indian as near Fort Edward as he dared to approach, when he placed it in a split stick, near a frequented path in the forest. It was found, was conveyed to Albany, and gave great joy to his friends. He remained in Canada three years, when he returned, married his affianced, and died in Washington County, in the year 1820, at the age of eighty-three years.

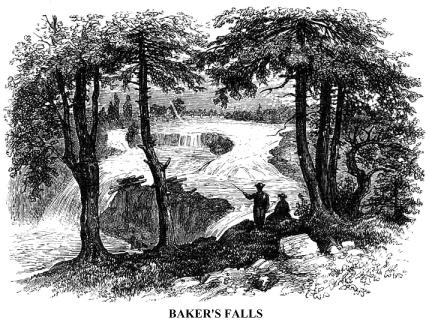

Baker's Falls are about half-way between Sandy Hill and Fort Edward. The river is about four hundred feet in width, and the entire descent of water, in the course of a mile, is between seventy and eighty feet. As at Glen's Falls, the course of the river is made irregular by huge masses of rocks, and it rushes in foaming cascades to the chasm below. The best view is from the foot of the falls, but as these could not be reached from the eastern side, on which the paper-mills stand, without much difficulty and some danger, I sketched a less imposing view from the high rocky bank on their eastern margin. This affords a glimpse of the milldam above the great fall, the village of Sandy Hill in the distance, and the piers of a projected railway bridge in the stream at the great bend. The direction of the railway was changed after these piers were built at a heavy expense, and they remain as monuments of caprice, or of something still less commendable.

Fort Edward, five miles below Glen's Falls, by the river's

course, was earliest known as the great carrying  place,

it being the point of overland departure for Lake Champlain, across the isthmus

of five-and-twenty miles. It has occupied an important position in the history

of New York from an early period, and at the time we are considering was a

very thriving village of about two thousand inhabitants.

place,

it being the point of overland departure for Lake Champlain, across the isthmus

of five-and-twenty miles. It has occupied an important position in the history

of New York from an early period, and at the time we are considering was a

very thriving village of about two thousand inhabitants.

In the year 1696, the unscrupulous Governor Fletcher granted to one of his favourites, whom he styled "our Loving Subject, the Reverend Godfridius Dellius, Minister of the Gospell att our city of Albany," a tract of land lying upon the east side of the Hudson, between the northernmost bounds of the Saratoga patent, and a point of Lake Champlain, a distance of seventy miles, with an average width of twelve miles. For this domain the worldly-minded clergyman was required, in the language of the grant, to pay, "on the feast-day of the Annunciation of our blessed Virgin Mary, at our City of New York, the Annual Rent of one Raccoon Skin, in Lien and Steade of all other Rents, Services, Dues, Dutyes, and Demands whatsoever for the said Tract of Land, and Islands, and Premises." Governor Belloment soon succeeded Fletcher, and, through his influence, the legislature of the province annulled this and other similar grants. That body, exercising ecclesiastical as well as civil functions, also passed a resolution, suspending Dellius from the ministry, for "deluding the Maquaas (Mohawk) Indians, and illegal and surreptitious obtaining of said grant." Dellius denied the authority of the legislature, and, after contesting his claim for a while, he returned to Holland. There he transferred his title to the domain to the Rev. John Lydius, who became Dellius's successor in the ministry at Albany, in 1703. Lydius soon afterward built a stone trading-house upon the site of Fort Edward. Its door and windows were strongly barred, and near the roof the walls were pierced for musketry. It was erected upon a high mound, and palisaded, as a defence against enemies.

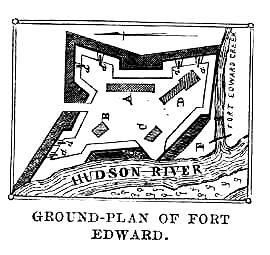

In 1709 an expedition was prepared for the conquest of Canada.

The commander of the division to attack  Montreal

was Francis Nicholson, who had been lieutenant-governor of the province of

New York. Under his direction a military road, forty miles in length, was

opened from Saratoga, on the east side of the Hudson, to White Hall, on Lake

Champlain. Along this route three forts were erected. The upper one was named

Fort Anne, in honour of the Queen of England; the middle one, of which Lydius's

house formed a part, was called Fort Nicholson, in honour of the commander;

and the lower one, just below the mouth of the Batten-Kill, was named Fort

Saratoga. Almost fifty years later, when a provincial army, under General

Johnson, of the Mohawk valley, and General Lyman, of Connecticut, was moving

forward to drive the French from Lake Champlain, a strong irregular quadrangular

fort was erected by the latter officer, upon the site of Fort Nicholson, and

the fortification was called Fort Lyman, in his honour. It was not fairly

completed when a successful battle was fought with the French and Indians

under the Baron Dieskau, at the head of Lake George, the honours of which

were more greatly due to Lyman than Johnson. But the latter was chief commander.

His king, as we have seen, gave him the honours of knighthood and £4,000.

With a mean spirit of jealousy, Johnson not only omitted to mention General

Lyman in his despatches, but changed the name of the fort which he had erected,

to Edward, in honour of one of the royal family of England.

Montreal

was Francis Nicholson, who had been lieutenant-governor of the province of

New York. Under his direction a military road, forty miles in length, was

opened from Saratoga, on the east side of the Hudson, to White Hall, on Lake

Champlain. Along this route three forts were erected. The upper one was named

Fort Anne, in honour of the Queen of England; the middle one, of which Lydius's

house formed a part, was called Fort Nicholson, in honour of the commander;

and the lower one, just below the mouth of the Batten-Kill, was named Fort

Saratoga. Almost fifty years later, when a provincial army, under General

Johnson, of the Mohawk valley, and General Lyman, of Connecticut, was moving

forward to drive the French from Lake Champlain, a strong irregular quadrangular

fort was erected by the latter officer, upon the site of Fort Nicholson, and

the fortification was called Fort Lyman, in his honour. It was not fairly

completed when a successful battle was fought with the French and Indians

under the Baron Dieskau, at the head of Lake George, the honours of which

were more greatly due to Lyman than Johnson. But the latter was chief commander.

His king, as we have seen, gave him the honours of knighthood and £4,000.

With a mean spirit of jealousy, Johnson not only omitted to mention General

Lyman in his despatches, but changed the name of the fort which he had erected,

to Edward, in honour of one of the royal family of England.

Fort Edward was an important military post during the whole of the French and Indian war,--that Seven Years' War which cost England more than a hundred millions of pounds sterling, and laid one of the broadest of the foundation-stones of her immense national debt. There, on one occasion, Israel Putnam, a bold provincial partizan, and afterward a major-general in the American revolutionary army, performed a most daring exploit. It was winter, and the whole country was covered with deep snow. Early in the morning of a mild day, one of the rows of wooden barracks in the fort took fire; the flames had progressed extensively before they were discovered. The garrison was summoned to duty, but all efforts to subdue the fire were in vain. Putnam, who was stationed upon Roger's Island, opposite the fort, crossed the river upon the ice with some of his men, to assist the garrison. The fire was then rapidly approaching the building containing the powder-magazine. The danger was becoming every moment more imminent and frightful, for an explosion of the powder would destroy the whole fort and many lives. The water-gate was thrown open, and soldiers were ordered to bring filled buckets from the river. Putnam mounted to the roof of the building next to the magazine, and, by means of a 'ladder, he was supplied with water. Still the fire raged, and the commandant of the fort, perceiving Putnam's danger, ordered him down. The unflinching major begged permission to remain a little longer. It was granted, and he did not leave his post until he felt the roof beneath him giving way. It fell, and only a few feet from the blazing mass was the magazine building, its sides already charred with the heat. Unmindful of the peril, Putnam placed himself between the fire and the sleeping power in the menaced building, which a spark might arouse to destructive activity. Under a shower of cinders, he hurled bucket-full of water upon the kindling magazine, with ultimate success. The flames were subdued, the magazine and remainder of the fort were saved, and the intrepid Putnam retired from the terrible conflict amidst the huzzas of his companions in arms. He was severely wounded in the contest. His mittens were burned from his hands, and his legs, thighs, arms, and face were dreadfully blistered. For a month he was a suffering invalid in the hospital.

Fort Edward was strengthened by the republicans, and properly garrisoned, when the revolution broke out in 1775. When General Burgoyne, with his invading army of British regulars, hired Germans, French, Canadians, and Indians, appeared at the foot of Lake Champlain, General Philip Schuyler was the commander-in-chief of the republican army in the Northern Department. His head-quarters were at Fort Anne, and General St. Clair commanded the important post of Ticonderoga. In July, Burgoyne came sweeping down the lake triumphantly. St. Clair fled from Ticonderoga, and his army was scattered and sorely smitten in the retreat. When the British advanced to Skenesborough, at the head of the lake, Schuyler retreated to Fort Edward, felling trees across the old military road, demolishing the causeways over the great Kingsbury marshes, and destroying the bridges, to obstruct the invader's progress. With great labour and perseverance Burgoyne moved forward, and on the 29th of July he encamped upon the high bank of the Hudson, at the great bend where the village of Sandy Hill now stands.

At this time a tragedy occurred near Fort Edward, which produced a great sensation throughout the country, and has been a theme for history, poetry, romance, and song. It was the death of Jenny M'Crea, the daughter of a Scotch Presbyterian clergyman, who is described as lovely in disposition, graceful in manners, and so intelligent and winning in all her ways, that she was a favourite of all who knew her. She was visiting a Tory friend at Fort Edward at this time, and was betrothed to a young man of the neighbourhood, who was a subaltern in Burgoyne's army. On the approach of the invaders, her brother, who lived near, fled, with his family, down the river, and desired Jenny to accompany them. She preferred to stay under the protection of her Tory friend, who was a widow, and a cousin of General Fraser, of Burgoyne's army.

Burgoyne had found it difficult to restrain the cruelty of his Indians. To secure their co-operation he had offered them a bounty for prisoners and scalps, at the same time forbidding them to kill any person not in arms for the sake of scalps. The offer of bounties stimulated the savages to seek captives other than those in the field, and they went out in small parties for the purpose. One of these prowled around Fort Edward early on the morning after Burgoyne arrived at Sandy Hill, and, entering the house where Jenny was staying, carried away the young lady and her friend. A Negro boy alarmed the garrison, and a detachment was sent after the Indians, who were fleeing with their prisoners toward the camp. They had caught two houses, and on one of them Jenny was already placed by them, when the detachment assailed them with a valley of musketry. The savages were unharmed, but one of the bullets mortally wounded their fair captive. She fell and expired, as tradition relates, near a pine-tree, which remained as a memorial of the tragedy until a few years ago. Having lost their prisoner, they secured her scalp, and, with her black tresses wet with her warm blood, they hastened to the camp. The friend of Jenny had just arrived, and the locks of the maiden, which were of great length and beauty, were recognized by her. She charged the Indians with her murder, which they denied, and told the story substantially as it is here related.

This appears, from corroborating circumstances, to be the simple truth of a story which, as it went from lip to lip, became magnified into a tale of darkest horror, and produced wide-spread indignation. General Gates, who had just superseded General Schuyler in the command of the northern army, took advantage of the excitement which it produced, to increase the hatred of the British in the hearts of the people, and he charged Burgoyne with crimes utterly foreign to that gentleman's nature. In a published letter, he accused him of hiring savages to "scalp Europeans and the descendants of Europeans;" spoke of Jenny as having been "dressed to meet her promised husband, but met her murderers," employed by Burgoyne; asserted that she, with several women and children, had been taken "from the house into the woods, and there scalped and mangled in a most shocking manner;" and alleged that he had "paid the price of blood!" This letter, so untruthful and ungenerous, was condemned by Gates's friends in the army. But it had the desired effect; and the sad story of Jenny's death was used with power against the ministry by the opposition in the British parliament.

The lover of Jenny left the army, and settled in Canada, where he lived to be an old man. He was naturally gay and garrulous, but after that event he was ever sad and taciturn. He never married, and avoided society. When the anniversary of the tragedy approached, he would shut himself in his room, and refuse to see his most intimate acquaintances; and at all times his friends avoided speaking of the American revolution in his presence. The body of Jenny was buried on her brother's land: it was re-interred at Fort Edward in 1826, with imposing ceremonies; and again in 1852, her remains found a new resting-place in a beautiful cemetery, half-way between Fort Edward and Sandy Hill. Her grave is near the entrance; and upon a plain white marble stone, six feet in height, standing at its head, is the following inscription:--

"Here

rest the remains of Jane M'Crea, aged 17; made captive and murdered by a band

of Indians, while on a visit to a relative in the neighbourhood, A.D. 1777.

To commemorate one of the most thrilling incidents in the annals of the American

revolution, to do justice to the fame of the gallant British officer to whom

she was affianced, and as a simple tribute to the memory of the departed,

this stone is erected by her niece, Sarah Hanna Payne, A.D. 1852."

"Here

rest the remains of Jane M'Crea, aged 17; made captive and murdered by a band

of Indians, while on a visit to a relative in the neighbourhood, A.D. 1777.

To commemorate one of the most thrilling incidents in the annals of the American

revolution, to do justice to the fame of the gallant British officer to whom

she was affianced, and as a simple tribute to the memory of the departed,

this stone is erected by her niece, Sarah Hanna Payne, A.D. 1852."

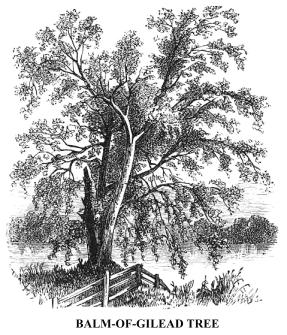

No relic of the olden time now remains at Fort Edward, excepting a few logs of the fort on the edge of the river, some faint traces of the embankments, and a magnificent Balm-of-Gilead tree, which stood, a sapling, at the water-gate, when Putnam saved the magazine. It has three huge trunks, springing from the roots. One of them is more than half decayed, having been twice riven by lightning within a few years. Upon Rogers's Island, in front of the town, where armies were encamped, and a large block-house stood, Indian arrow-heads, bullets, and occasionally a piece of "cob-money,"* are sometimes upturned by the plough.

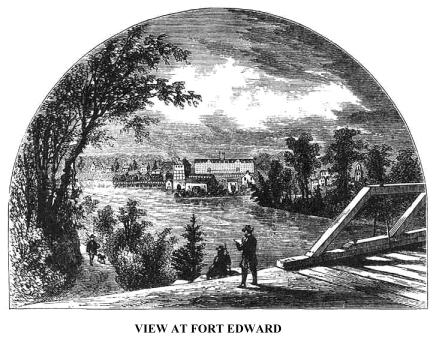

A picture of the village of Fort Edward, in 1820, shows only

six houses and a church; now, as we have  observed,

it was a busy town with two thousand inhabitants. Its chief industrial establishment

was an extensive blast-furnace for converting iron ore into the pure metal.

Upon rising ground, and overlooking the village and surrounding country, was

a colossal educational establishment, called the Fort Edward Institute. The

building was erected, and its affairs were controlled, by the Methodist denomination,

and it was widely known as one of the most flourishing institutions of its

kind in the country. The building was five stories in height, and was surrounded

by pleasant grounds. It is seen in our view at Fort Edward, which was taken

from the end of the bridge that connects Rogers's Island with the western

shore of the Hudson. The blast-furnace, and a portion of the Fort Edward dam,

built by the State for the use of the Champlain Canal, is also seen in the

picture.

observed,

it was a busy town with two thousand inhabitants. Its chief industrial establishment

was an extensive blast-furnace for converting iron ore into the pure metal.

Upon rising ground, and overlooking the village and surrounding country, was

a colossal educational establishment, called the Fort Edward Institute. The

building was erected, and its affairs were controlled, by the Methodist denomination,

and it was widely known as one of the most flourishing institutions of its

kind in the country. The building was five stories in height, and was surrounded

by pleasant grounds. It is seen in our view at Fort Edward, which was taken

from the end of the bridge that connects Rogers's Island with the western

shore of the Hudson. The blast-furnace, and a portion of the Fort Edward dam,

built by the State for the use of the Champlain Canal, is also seen in the

picture.

A

carriage-ride from Fort Edward down the valley of the Hudson, especially on

its western side, affords exquisite enjoyment to the lover of beautiful scenery

and the displays of careful cultivation. The public road follows the river-bank

nearly all the way to Troy, a distance of forty miles, and the traveler seldom

loses sight of the noble stream, which is frequently divided by islands, some

cultivated, and others heavily wooded. The most important of these, between

Fort Edward and Schuylerville, are Munro's, Bell's, Taylor's, Galusha's, and

Payne's; the third one containing seventy acres. The shores of the river are

everywhere fringed with beautiful shade-trees and shrubbery, and fertile lands

spread out on every side.

A

carriage-ride from Fort Edward down the valley of the Hudson, especially on

its western side, affords exquisite enjoyment to the lover of beautiful scenery

and the displays of careful cultivation. The public road follows the river-bank

nearly all the way to Troy, a distance of forty miles, and the traveler seldom

loses sight of the noble stream, which is frequently divided by islands, some

cultivated, and others heavily wooded. The most important of these, between

Fort Edward and Schuylerville, are Munro's, Bell's, Taylor's, Galusha's, and

Payne's; the third one containing seventy acres. The shores of the river are

everywhere fringed with beautiful shade-trees and shrubbery, and fertile lands

spread out on every side.

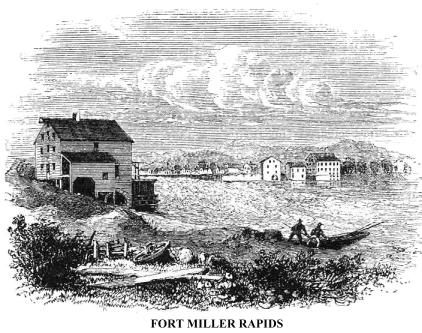

Seven miles below Fort Edward, on the western shore, is the site of Fort Miller, erected during the French and Indian war; and opposite, at the head of foaming rapids, which afford fine water-power for mills, is the village of Fort Miller, then containing between two and three hundred inhabitants. Not a vestige of the fort remains. The river here rushes over a rough rocky bed, and falls fifteen or twenty feet in the course of eighty rods. Here was the scene of another of Putnam's adventures during the old war. He was out with a scouting party, and was lying alone in a batteau on the east side of the river, when he was surprised by some Indians; he could not cross the river swiftly enough to escape the balls of their rifles, and there was no alternative but to go down the foaming rapids. He did not hesitate a moment. To the astonishment of the savages, he steered directly down the current, amid whirling eddies and over ragged and shelving rocks, and in a few moments his vessel had cleared the rushing waters, and was gliding upon the tranquil river below, far out of reach of their weapons. The Indians dared not make the perilous voyage: they regarded Putnam as God-protected, and believed that it would be an affront to the Great Spirit to make further attempts to kill him with powder and ball.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.