CHAPTER EIGHT, Part TWO

At

the Oak Hill station the tourist upon the railway will leave it for a trip

to the Katzbergs before him, upon which may be seen, at the distance of eight

miles in an air line, the "Mountain House," the famous resort for

hundreds of people who escape from the dust of cities during the heat of summer.

The river is crossed on a steam ferry-boat, and good omnibuses convey travelers

from it to the pleasant village of Katz-Kill, which lies upon a slope on the

left bank of the stream bearing the same name, less than half a mile from

its mouth. At the village, conveyances are ready at all times to take the

tourist to the Mountain House, twelve miles distant by the road, which passes

through a picturesque and highly cultivated country, to the foot of the mountain.

Before making this tour, however, the traveler should linger awhile on the

banks of the Katz-Kill, from the Hudson a few miles into the country, for

there may be seen, from different points of view, some of the most charming

scenery in the world. Every turn in the road, every bend in the stream, presents

new and attractive pictures, remarkable for beauty and diversity in outline,

colour, and aërial perspective. The solemn Katzbergs, sublime in form,

and mysterious in their dim, incomprehensible, and ever-changing aspect, almost

always form a prominent feature in the landscape. In the midst of this scenery,

Cole, the eminent painter, loved to linger when the shadows of the early morning

were projected towards the mountain, then bathed in purple mists; or at evening,

when these lofty hills, then dark and awful, cast their deep shadows over

more than half the country below, between their bases and the river. Charmed

with this region, Cole made it at first a summer retreat, and finally his

permanent residence, and there, in a fine old family mansion, delightfully

situated to command a full view of the Katzberg range and the intervening

country, his spirit passed from earth, while a sacred poem, created by his

wealthy imagination and deep religious sentiment, was finding expression upon

his easel in a series of fine pictures, like those of "The Course of

Empire," and "The Voyage of Life." He entitled the series,

"The Cross and the World." Only one of the pictures was finished.

One had found form in a "study" only, and two others were partly

finished on the large canvas. Another, making the fifth (the number in the

series), was about half completed, with some figures sketched in with white

chalk. So they remain, just as the master left them, and so remains his studio.

It is regarded by his devoted widow as a place too sacred for the common gaze.

The stranger never enters it.

At

the Oak Hill station the tourist upon the railway will leave it for a trip

to the Katzbergs before him, upon which may be seen, at the distance of eight

miles in an air line, the "Mountain House," the famous resort for

hundreds of people who escape from the dust of cities during the heat of summer.

The river is crossed on a steam ferry-boat, and good omnibuses convey travelers

from it to the pleasant village of Katz-Kill, which lies upon a slope on the

left bank of the stream bearing the same name, less than half a mile from

its mouth. At the village, conveyances are ready at all times to take the

tourist to the Mountain House, twelve miles distant by the road, which passes

through a picturesque and highly cultivated country, to the foot of the mountain.

Before making this tour, however, the traveler should linger awhile on the

banks of the Katz-Kill, from the Hudson a few miles into the country, for

there may be seen, from different points of view, some of the most charming

scenery in the world. Every turn in the road, every bend in the stream, presents

new and attractive pictures, remarkable for beauty and diversity in outline,

colour, and aërial perspective. The solemn Katzbergs, sublime in form,

and mysterious in their dim, incomprehensible, and ever-changing aspect, almost

always form a prominent feature in the landscape. In the midst of this scenery,

Cole, the eminent painter, loved to linger when the shadows of the early morning

were projected towards the mountain, then bathed in purple mists; or at evening,

when these lofty hills, then dark and awful, cast their deep shadows over

more than half the country below, between their bases and the river. Charmed

with this region, Cole made it at first a summer retreat, and finally his

permanent residence, and there, in a fine old family mansion, delightfully

situated to command a full view of the Katzberg range and the intervening

country, his spirit passed from earth, while a sacred poem, created by his

wealthy imagination and deep religious sentiment, was finding expression upon

his easel in a series of fine pictures, like those of "The Course of

Empire," and "The Voyage of Life." He entitled the series,

"The Cross and the World." Only one of the pictures was finished.

One had found form in a "study" only, and two others were partly

finished on the large canvas. Another, making the fifth (the number in the

series), was about half completed, with some figures sketched in with white

chalk. So they remain, just as the master left them, and so remains his studio.

It is regarded by his devoted widow as a place too sacred for the common gaze.

The stranger never enters it.

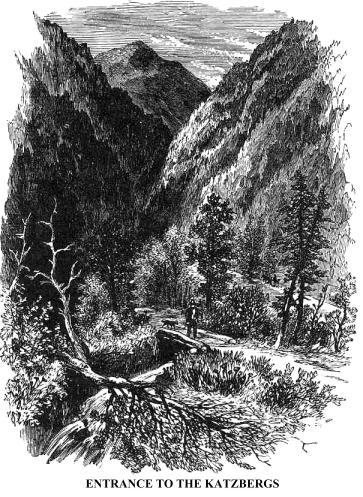

The range of the Katzbergs * rises abruptly from the plain on their eastern side, where the road that leads to the Mountain House enters them, and follows the margin of a deep, dark glen, through which flows a clear mountain stream seldom seen by the traveler, but heard continually for a mile and a half, as, in swift rapids or in little cascades, it hurries to the plain below. The road is sinuous, and in its ascent along the side of that glen, or more properly magnificent gorge, it is so enclosed by the towering hills on one side and the lofty trees that shoot up on the other, that little can be seen beyond a few rods, except the sky above, or glimpses of some distant summit, until the pleasant nook in the mountain is reached, wherein the Cabin of Rip Van Winkle is nestled. After that the course of the road is more nearly parallel with the river and the plain, and through frequent vistas glimpses may be caught of the country below, that charm the eye, excite the fancy and the imagination, and make the heart throb quicker and stronger with pleasurable emotions.

* The Indians called this range of hills On-ti-O-ra, signifying, Mountains of the Sky, for in some conditions of the atmosphere they are said to appear like a heavy cumulous cloud above the horizon. The Dutch called them Katzbergs, or Cat Mountains, because of the prevalence of panthers and wild-cats upon them. The word Cats-Kill is partly English and partly Dutch: Katz-Kill, Dutch; Cats-Creek, English.

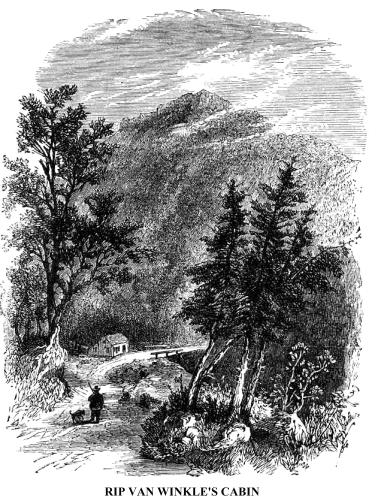

Rip's cabin was a decent frame-house, as the Americans call

dwellings made of wood, with two rooms,  standing

by the side of the road half-way from the plain to the Mountain House, at

the head of the gorge, along whose margin the traveler has ascended. It was

so called because it stood within the "amphitheatre" reputed to

be the place where the ghostly nine-pin players of Irving's charming story

of Rip Van Winkle held their revel, and where thirsty Rip lay down to his

long repose by "that wicked flagon," watched by his faithful dog

Wolf, and undisturbed by the tongue of Dame Van Winkle. As one stands upon

the rustic bridge, in front of the cabin, and looks down the dark glen, up

to the impending cliffs, or around in that rugged amphitheatre, the scene

comes up vividly in memory, and the "company of odd-looking personages

playing at nine-pins" reappear. "Some wore short doublets, others

jerkins, with long knives in their belts, and most of them had enormous breeches,

of similar style with that of the guides. Their visages, too, were peculiar:

one had a large head, broad face, and small piggish eyes; the face of another

seemed to consist entirely of a nose, and was surmounted by a white sugar-loaf

hat, set off with a little red cock's tail. They all had beards, of various

shapes and colours. There was one who seemed to be the commander. He was a

stout old gentleman, with a weather-beaten countenance; he wore a laced doublet,

broad belt and hanger, and high-crowned hat and feather, red stockings, and

high-heeled shoes with roses in them. What seemed particularly odd to Rip

was, that though these folks were evidently amusing themselves, yet they maintained

the gravest faces, the most mysterious silence, and were withal the most melancholy

party of pleasure he had ever witnessed. Nothing interrupted the stillness

of the scene but the noise of the balls, which, whenever they were rolled,

echoed along the mountains like rumbling peals of thunder."

standing

by the side of the road half-way from the plain to the Mountain House, at

the head of the gorge, along whose margin the traveler has ascended. It was

so called because it stood within the "amphitheatre" reputed to

be the place where the ghostly nine-pin players of Irving's charming story

of Rip Van Winkle held their revel, and where thirsty Rip lay down to his

long repose by "that wicked flagon," watched by his faithful dog

Wolf, and undisturbed by the tongue of Dame Van Winkle. As one stands upon

the rustic bridge, in front of the cabin, and looks down the dark glen, up

to the impending cliffs, or around in that rugged amphitheatre, the scene

comes up vividly in memory, and the "company of odd-looking personages

playing at nine-pins" reappear. "Some wore short doublets, others

jerkins, with long knives in their belts, and most of them had enormous breeches,

of similar style with that of the guides. Their visages, too, were peculiar:

one had a large head, broad face, and small piggish eyes; the face of another

seemed to consist entirely of a nose, and was surmounted by a white sugar-loaf

hat, set off with a little red cock's tail. They all had beards, of various

shapes and colours. There was one who seemed to be the commander. He was a

stout old gentleman, with a weather-beaten countenance; he wore a laced doublet,

broad belt and hanger, and high-crowned hat and feather, red stockings, and

high-heeled shoes with roses in them. What seemed particularly odd to Rip

was, that though these folks were evidently amusing themselves, yet they maintained

the gravest faces, the most mysterious silence, and were withal the most melancholy

party of pleasure he had ever witnessed. Nothing interrupted the stillness

of the scene but the noise of the balls, which, whenever they were rolled,

echoed along the mountains like rumbling peals of thunder."

Such was the company to whom hen-pecked Rip Van Winkle, wandering upon the mountains on a squirrel hunt, was introduced by a mysterious stranger carrying a keg of liquor, at autumnal twilight. And there it was that thirsty Rip drank copiously, went to sleep, and only awoke when twenty years had rolled away. His dog was gone, and his rusty gun-barrel, bereft of its stock, lay by his side. He doubted his identity. He sought the village tavern and its old frequenters; his own house, and his faithful Wolf. Alas! everything was changed, except the river and the mountains. Only one thing gave him real joy--Dame Van Winkle's terrible tongue had been silenced for ever by death! He was a mystery to all, and more a mystery to himself than to others. Whom had he met in the mountains? those queer fellows that reminded him of "the figures in an old Flemish painting, in the parlour of Dominic Van Schaick, the village parson. Sage Peter Vonderdonck was called to explain the mystery; and Peter successfully responded. He asserted that it was a fact, handed down from his ancestor, the historian, that the Kaats-Kill Mountains had always been haunted by strange beings. That it was affirmed that the great Hendrick Hudson, the first discoverer of the river and country, kept a kind of vigil there every twenty years, with his crew of the Half-Moon, being permitted in this way to revisit the scenes of his enterprise, and kept a guardian eye upon the river and the great city called by his name. That his father had once seen them, in their old Dutch dresses, playing at nine-pins in a hollow of the mountain; and that himself had heard, one summer afternoon, the sound of their balls, like distant peals of thunder." Rip's veracity was vindicated; his daughter gave him a comfortable home; and the grave historian of the event assures us that the Dutch inhabitants, "even to this day, never hear a thunder-storm of a summer afternoon about the Kaats-Kill, but they say, Hendrick Hudson and his crew are at their game of nine-pins."

The Van Winkle of our day, who lived in the cottage by the mountain road-side as long as a guest lingered at the great mansion above him, was no kin to old Rip, and we strongly suspect that his name was borrowed; but he kept refreshments that strengthened many a weary toiler up the mountain--liquors equal, no doubt, to those in the "wicked flagons" that the ancient one served to the ghostly company--and from a rude spout poured cooling draughts into his cabin from a mountain spring, more delicious than ever came from the juice of the grape.

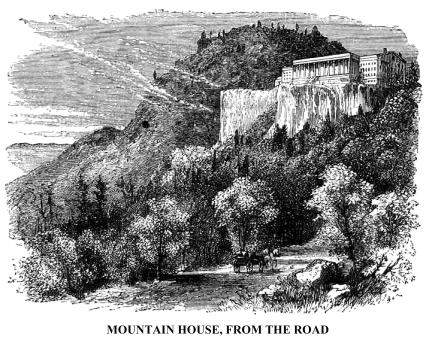

There

are many delightful resting-places upon the road, soon after leaving Rip's

cabin, as we toil wearily up the mountain, where the eye takes in a magnificent

panorama of hill and valley, forest and river, hamlet and village, and thousands

of broad acres where herds graze and the farmer gathers his crops,--much of

it dimly refined because of distance--a beautifully coloured map rather than

a picture. These delight the eye and quicken the pulse, as has been remarked;

but there is one place upon that road where the ascending weary ones enjoy

more exquisite pleasure for a moment than at any other point in all that mountain

region. It is at a turn in the road where the Mountain House stands suddenly

before and above the traveler, revealed in perfect distinctness--column, capital,

window, rock, people--all apparently only a few rods distant. There, too,

the road is level, and the traveler rejoices in the assurance that the toilsome

journey is at an end; when, suddenly, he finds himself, like the young pilgrim

in Cole's "Voyage of Life," disappointed in his course. The road

that seemed to be leading directly to that beautiful mansion, upon the crag

just above him, turns away, like the stream that appeared to be taking the

ambitious young voyager directly to the shadowy temple of Fame in the clouds;

and many a weary step must be taken, over a crooked, hilly road, before the

traveler can reach the object of his journey.

There

are many delightful resting-places upon the road, soon after leaving Rip's

cabin, as we toil wearily up the mountain, where the eye takes in a magnificent

panorama of hill and valley, forest and river, hamlet and village, and thousands

of broad acres where herds graze and the farmer gathers his crops,--much of

it dimly refined because of distance--a beautifully coloured map rather than

a picture. These delight the eye and quicken the pulse, as has been remarked;

but there is one place upon that road where the ascending weary ones enjoy

more exquisite pleasure for a moment than at any other point in all that mountain

region. It is at a turn in the road where the Mountain House stands suddenly

before and above the traveler, revealed in perfect distinctness--column, capital,

window, rock, people--all apparently only a few rods distant. There, too,

the road is level, and the traveler rejoices in the assurance that the toilsome

journey is at an end; when, suddenly, he finds himself, like the young pilgrim

in Cole's "Voyage of Life," disappointed in his course. The road

that seemed to be leading directly to that beautiful mansion, upon the crag

just above him, turns away, like the stream that appeared to be taking the

ambitious young voyager directly to the shadowy temple of Fame in the clouds;

and many a weary step must be taken, over a crooked, hilly road, before the

traveler can reach the object of his journey.

The grand rock-platform, upon which the Mountain House stands, is reached at last; and then comes the full recompense for all weariness. Bathed--immersed--in pure mountain air, almost three thousand feet above tide-water, full, positive, enduring rest is given to every muscle after a half hour's respiration of that invigorating atmosphere; and soul and limb are ready for a longer, loftier, and more rugged ascent.

There is something indescribable in the pleasure experienced during the first hour passed upon the piazza of the Mountain House, gazing upon the scene toward the east. That view has been described a thousand times. I shall not attempt it. Much rhetoric, and rhyme, and sentimental platitudes have been employed in the service of description, but none have conveyed to my mind a picture so graphic, truthful, and satisfactory as Natty Bumpo's reply to Edward's question, in one of Cooper's "Leather-Stocking Tales," "What see you when you get there?"

",Creation!" said Natty, dropping the end of his rod into the water, and sweeping one hand around him in a circle, "all creation, lad. I was on that hill when Vaughan burnt' Sopus, in the last war, and I saw the vessels come out of the Highlands as plainly as I can see that lime-scow rowing into the Susquehanna, though one was twenty times further from me than the other.* The river was in sight for seventy miles under my feet, looking like a curled shaving, though it was eight long miles to its banks. I saw the hills in the Hampshire Grants, the Highlands of the river, and all that God had done, or man could do, as far as the eye could reach--you know that the Indians named me for my sight, lad+ -- and from the flat on the top of that mountain, I have often found the place where Albany stands; and as for `Sopus! the day the royal troops burnt the town, the smoke seemed so nigh that I thought I could hear the screeches of the women."

* Reference is here made to the burning of the village of Kingston (whose Indian name of E-so-pus was retained until a recent period), by a British force under General Vaughan, in the Autumn of 1777.

+ "Hawk-Eye."

"It must have been worth the toil, to meet with such a glorious view."

"If being the best part of a mile in the air, and having men's farms at your feet, with rivers looking like ribands, and mountains bigger than the `Vision,' seeming to be haystacks of green grass under you, give any satisfaction to a man, I can recommend the spot."

The aërial pictures seen from the Mountain House are sometimes marvelous, especially during a shower in the plain, when all is sunshine above, while the lightning plays and the thunder rolls far below the dwellers upon the summits; or after a storm, when mists are driving over the mountains, struggling with the wind and sun, or dissolving into invisibility in the pure air. At rare intervals, an apparition, like the spectre of the Brocken, may be seen. A late writer, who was once there during a summer storm, was favoured with the sight. The guests were in the parlour, when it was announced that "the house was going past on the outside!" All rushed to the piazza, and there, sure enough, upon a moving cloud, more dense than the fog that enveloped the mountain, was a perfect picture of the great building, in colossal proportions. The mass of vapour was passing slowly from north to south, directly in front, at a distance, apparently, of two hundred feet from the building, and reflected the noble Corinthian columns which ornament the front of the building, every window, and all the spectators. The cloud moved on, and "ere long," says the writer, "we saw one pillar disappear, and then another. We, ourselves, who were expanded into Brobdignags in size, saw the gulf into which we were to enter and be lost. I almost shuddered when my turn came, but there was no eluding my fate; one side of my face was veiled, and in a moment the whole had passed like a dream. An instant before, and we were the inhabitants of a 'gorgeous palace,' but it was the 'baseless fabric of a vision,' and now there was left 'not a wreck behind.'"

As a summer shower passes over the plain below, the effect

at the Mountain House is sometimes truly  grand,

even when the lightning is not seen or the thunder heard. A young woman sitting

at the side of the writer when this page was penned, and who had recently

visited that eyrie, recorded her vision and impressions on the spot. "The

whole scene before us," she says, "was a vast panorama, constantly

varying and changing. The blue of the depths and distances--clouds, mountains,

and shadows--was such that the perception entered into our very souls. How

shall I describe the colour? It was not mazarine, because there was no blackness

in it; it was not sunlit atmosphere, because there was no white brightness

in it; and yet there was a sort of hidden, beaming brilliancy, that completely

absorbed our eyes and hearts. It was not the blue of water, because it was

not liquid or crystal-like; it was something as the calm, soft, lustre of

a steady blue eye..... And how various were the forms and motions of the vapour!

Hills, mountains, domes, pyramids, wreaths and sprays of mist arose, mounted,

hung, fell, curled, and almost leaped before us, white with their own spotlessness,

but not bright with the sun's rays, for the luminary was still obscured.....We

looked down to behold what we might discover. A breath of heaven cleared the

mist from below,--softly at first, but gradually more decisive. Larger and

darker became a spot in the magic depths, when, lo! as in a vision, fields,

trees, fences, and the habitations of men were revealed before our eyes. For

the first time something real and refined lay before us, far down in that

wonderful gulf. Far beneath heaven and us slept a speck of creation, unlighted

by the evening rays that touched us, and colourless in the twilight obscurity.

Intently we watched the magic glass, but--did we breathe upon its surface?--a

mist fell before us, and we looked up as if awakened from a dream."

grand,

even when the lightning is not seen or the thunder heard. A young woman sitting

at the side of the writer when this page was penned, and who had recently

visited that eyrie, recorded her vision and impressions on the spot. "The

whole scene before us," she says, "was a vast panorama, constantly

varying and changing. The blue of the depths and distances--clouds, mountains,

and shadows--was such that the perception entered into our very souls. How

shall I describe the colour? It was not mazarine, because there was no blackness

in it; it was not sunlit atmosphere, because there was no white brightness

in it; and yet there was a sort of hidden, beaming brilliancy, that completely

absorbed our eyes and hearts. It was not the blue of water, because it was

not liquid or crystal-like; it was something as the calm, soft, lustre of

a steady blue eye..... And how various were the forms and motions of the vapour!

Hills, mountains, domes, pyramids, wreaths and sprays of mist arose, mounted,

hung, fell, curled, and almost leaped before us, white with their own spotlessness,

but not bright with the sun's rays, for the luminary was still obscured.....We

looked down to behold what we might discover. A breath of heaven cleared the

mist from below,--softly at first, but gradually more decisive. Larger and

darker became a spot in the magic depths, when, lo! as in a vision, fields,

trees, fences, and the habitations of men were revealed before our eyes. For

the first time something real and refined lay before us, far down in that

wonderful gulf. Far beneath heaven and us slept a speck of creation, unlighted

by the evening rays that touched us, and colourless in the twilight obscurity.

Intently we watched the magic glass, but--did we breathe upon its surface?--a

mist fell before us, and we looked up as if awakened from a dream."

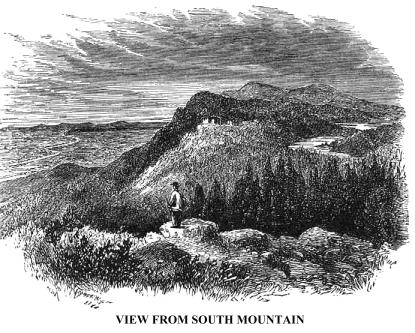

Although the Mountain House is far below the higher summits of the range, portions of four States of the Union, and an area of about ten thousand square miles, are comprised in the scope of vision from its piazza. From the top of the South Mountain near, and three hundred feet above the Mountain House, and of the North Mountain more distant and higher, a greater range of sight may be obtained, including a portion of a fifth State. From the latter, a majestic view of mountain scenery, and of the lowlands southward, may be obtained at the price of a little fatigue, for which full compensation is given. The Katers-Kill * lakes, lying in a basin a short distance from the Mountain House, with all their grand surroundings, the house itself, and the South Mountain, and the Round Top or Liberty Cap, form the middle ground; while in the dim distance the winding Hudson, with the Esopus, Shawangunk, and Highland ranges are revealed, the borders of the river dotted with villas and towns appearing mere white specks on the landscape.

*Kater is the Dutch for He-Cat--He-Cats Creek.

Copyright © 1998, -- 2004. Berry Enterprises. All rights reserved. All items on the site are copyrighted. While we welcome you to use the information provided on this web site by copying it, or downloading it; this information is copyrighted and not to be reproduced for distribution, sale, or profit.