Three Rivers

Hudson~Mohawk~Schoharie

History From America's Most Famous Valleys

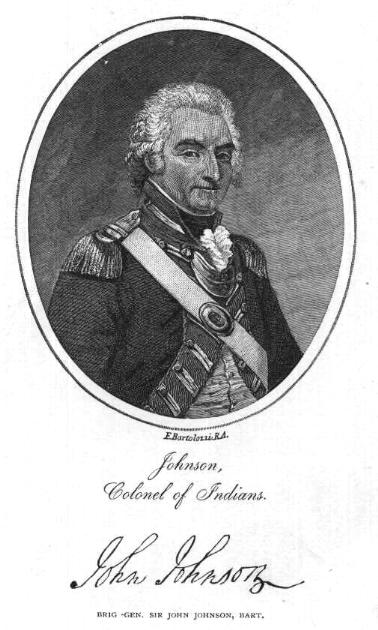

The Orderly Book of Sir John Johnson

During the Oriskany Campaign

1776-1777

Annotated by Wm. L. Stone

With an Historical Introduction illustrating the Life of Johnson by J. Watts

De Peyster, and Some Tracings from the Foot-Prints of the Tories, or Loyalists

in America by T. R. Myers.

Albany

Joel Munsell, 1882

ENGAGEMENT NEAR FOX'S MILLS,*

Often Styled

THE BATTLE OF KLOCK'S FIELD

19th October 1780.

"History is not now-a-days consulted as a faithful oracle; it is rather treated like the old lamp as too rusty, too old and homely, to bear light amidst the blaze of modern illumination, but more valuable as an instrument of incantation, which by occasional friction upon its surface, may conjure up mighty spirits to do the bidding of a master. Such an instrument in the hands of a good and faithful magician will not be employed upon baseless fabrications, that new power may dissolve, but in building upon the foundations of Truth, that shall still hold all together, in building upon the foundations of Truth, that shall still hold all together, in defiance of the agency of even the same enchantment to destroy the structures it has raised." SOUTHGATE'S "Many Thoughts on Many Things."

Of all the engagements which have occurred upon the soil of New York, the "cock-pit," of "the Flanders," of the Colonies, there is none which as been so misrepresented as this. There is very little basis for the narrative generally accepted as history. Envy, hatred and malice have painted every picture, and even gone so far as to malign the State commander, the scion of a family who risked more than any other for the Commonwealth, to conceal and excuse the bad conduct of his troops. As for the

*Sometimes confounded with that of Stone Arabia (on or near dePeyster Patent): East side of Caroga Creek where it empties into the Mohawk River, near St. Johnsville, Montgomery County, S. N. Y., sixty-three miles W. by N. of Albany.

leader of the Loyalists, it is no wonder that his reputation fared badly at the hands of a community whom he had made to suffer so severely for their sins against justice, his family connections, friends and himself. The State Brigadier-General was wrongfully accused and abused, although acquitted of every charge by his peers,* and highly commended for activity, fidelity, prudence, spirit and conduct. The Royal leader, like the State commander, was also subjected to the false accusation of want of courage, on the statement of a personal enemy; but, like his antagonist, received the highest commendation of his superior, a veteran and proficient.

Before attempting to describe what actually occurred on the date of the collision, a brief introduction is necessary to its comprehension. The distinguished Peter Van Schaack (Stone's " Sir William Johnson," II., 388) pronounced Sir "William Johnson " THE GREATEST CHARACTER OF THE. AGE," the ablest man who figured in our immediate Colonial history. He was certainly the benefactor of Central New York, the protector of its menaced frontier, the first who by victories stayed the flood-tide of French invasion. His son, Sir John, succeeded to the bulk of his vast possessions in the most troublous times of New York's history. He owed everything to the Crown and nothing to the People, and yet the People, because he would not betray his duty to the Crown, drove him forth

* "French's Gazetteer," 432 ; Stone's " Brant," II., 124-5; Stone's "Border Wars," ii., 126-7 ; Simm's "Schoharie County," 430-1; Campbell's "Border Wars," 199-201.

and despoiled him. More than once he returned in arms to punish and retrieve, at a greater hazard than any to which the mere professional soldier is subjected. By the detestable laws of this embryo State, even a peaceable return subjected him to the risk of a halter; consequently, in addition to the ordinary perils of battle, he fought, as it were, with a rope around his neck. There was no honorable captivity for him. The same pitiless revenge which, after King's Mountain (S. C.), in the same month and year (7th October, 1780), strung up a dozen Loyalist officers and soldiers would have sent him speedily to execution. The coldly cruel or unrelentingly severe-choose between the terms-Governor Clinton would have shown no pity to one who had struck harder and oftener than any other, and left the record of his visitations in letters of fire on vast tablets of ashes coherent with blood.

In 1777, through the battle-plans of Sir John, a majority of the effective manhood of the Mohawk-among these some of his particular persecutors-perished at Oriskany. Neither Sir John Johnson nor Brant had anything to do with Wyoming. This is indisputable, despite the bitter words and flowing verses of historians, so called, and poets, drawing false fancy pictures of what never had any actual existence. In 1779, his was the spirit which induced the Indians to make an effort to arrest Sullivan, and it was Sir John, at length, interposed between this General and his great objective, Niagara, if it was not the very knowledge that Sir John was concentrating forces in his front that caused Sullivan to turn back. In the following autumn (1779) he made himself master of the key of the "great portage" between Ontario and the Mohawk, and his farther visitation of the valley eastward was only frustrated by the stormy season on the great lake by which alone he could receive reinforcements and supplies.

In May, 1780, starting from Bulwagga Bay (near Crown Point) on Lake Champlain, he constructed a military road through the wilderness-of which vestiges are still plainly visible-ascended the Sacondaga, crossed the intervening watershed, and fell (on Sunday night, 21st May) with the suddenness of a waterspout upon his rebellious birthplace, accomplished his purpose, left behind him a dismal testimony of his visitation, and despite the pursuit of aggregated enemies, escaped with his recovered plate, rich booty and numerous prisoners.

It was during this expedition that Sir William's fishing house and summer house on the Sacondaga were destroyed, and it is a wonder Sir John did not burn to the ground the family hall at Johnstown. This was not a raid, but an invasion, which depended for success upon, at least, demonstrations by the British forces in New York. As in 1777 and 1779, and again in the fall of 1780, there was nothing done by the indolent professionals.

In August-September of the same year, he organized a second expedition at Lachine (nine miles above Montreal), ascended the St. Lawrence, crossed Lake Ontario, followed up the course of the Oswego River, coasted the southern shore of Oneida Lake, until he reached the mouth of Chittenango Creek (western boundary of Madison County and eastern of Onondaga County), where he left his batteaux and canoes, struck off southeastward up the Chittenango, then crossing the Unadilla and the Charlotte, (sometimes called the East branch of the Susquehanna), and descended in a tempest of flame into the rich settlements along the Schoharie, which he struck at what was known as the Upper Fort, now Fultonham, Schoharie County.*

Thence he wasted the whole of this rich valley to the mouth of this stream, and then turning westward completed the devastation of everything which preceding inroads had spared. (Stone's "Brant," II., 124.) The preliminary march through natural obstacles, apparently insurmountable to an armed force, was one of certainly 200 miles. The succeeding sweep and retreat embraced almost as many. The result, if reported with any correctness, might recall Sir Walter Scott's lines ("Vision of Don Roderick," Conclusion II.):

"While

downward on the land his legions press,

Before him it was rich with vine and flock,

And

smil'd like Eden in her summer dress,-

Behind their march a howling wilderness."

More than one contemporary statement attests that the invasion carried things back to the uncertainties of the old French inroads and reinvested Schenectady with the dangerous

*If the old maps of this then savage country are reliable, he may have crossed from the valley of the Charlotte into that of the Mohawk Branch of the Delaware, or the Papontuck Branch further east again. From either there was a portage of only a few miles to the Schoharie Kill.

honor of being considered again a frontier- post. (Hough's " Northern Invasion," 131, 144.)

The immediate local damage done by Sir John, within the territory affected by his visitation, was nothing in comparison to the consequences, militarily considered, without these. The destruction of breadstuffs and forage was enormous. "Washington and the army felt it, since the districts invaded and wasted were granaries on which the American commissariat and quartermaster's department depended in a great measure for the daily rations which they had to provide. The number of bushels of wheat and other grain rendered worthless "threatened alarming consequences." Eighty thousand bushels were lost in the Schoharie settlement alone. Washington admits this in a letter to the President of Congress, dated 7th November, 1780. Had the British military authorities in New York and in Canada been alive to the advantages to be derived from the condition of affairs in Central New York, they might have enabled Sir John to strike a blow that would have shaken the fabric of Revolution, throughout the Middle States, at least. Alas ! they seem to have been possessed with the spirit of inertion and incapacity, and the abandoned Loyalists might have exclaimed, with Uhland :

"Forward! Onward!

far and forth !

An earthquake shout awakes the North.

Forward !

Forward ! Onward ! far and forth !

And prove what gallant hearts are worth."

Forward ! "

The terrifying intelligence of the appearance of this little "army of vengeance" aroused the whole energy of coterminous districts; the militia were assembled in haste, and pushed forward to the point of danger, under Brigadier-General Robert van Rensselaer, of Claverack (now Columbia County), who were guided into the presence of their enemy literally by "pillars of fire by night and columns of smoke by day." Although he knew that he was pursued by forces treble or quadruple if not quintuple his own, Sir John continued to burn and destroy up to the very hour when his troops were obliged to lay aside the torch to resume their firelocks. In fact, if the two engagements of the 19th of October, 1770, were contemplated parts of a combined plan to overwhelm Sir John, he actually fought and burned simultaneously. To whomsoever a contemporaneous map of this country is accessible, it will be evident how vast a district was subjected to this war cyclone. On the very day (19th October) that van Rensselaer was at Fort Plain, the nourishing settlements of Stone Arabia (Palatine Township, Montgomery County), a few miles to the westward, were destroyed. Finding that he must fight, either to arrest pursuit or to insure retreat, Sir John hastily assembled some of his wearied troops, while others kept on burning in every direction, to engage the garrison of Fort Paris-constructed to protect the Stone Arabia settlement (Simm's "Schoharie County," 426)-which marched out to intercept him under Colonel Brown, an officer of undoubted ability and of tried courage. Brown's immediate force consisted of 130 men of the Massachusetts Levies, and a body of militia-70 and upwards-whose numbers and cooperation seemed to have been studiously concealed by almost every writer at the period ; that there were militia present is unquestionable. It is almost, if not absolutely, certain that Brown marched out of Fort Paris in pursuance of the orders and plan of van Rensselaer, in order to cut Sir John off from his line of retreat, and hold him or "head him" until van Rensselaer could fall upon him with overwhelming numbers. The same failure to cooperate in executing a very sensible piece of strategy sacrificed Harkheimer to Sir John at Oriskany, some three years previously, and resulted in a similar catastrophe. To appreciate and to forestall was the immediate and only solution. Sir John attacked Colonel Brown-like "now, on the head," as Suwarrow phrased it-about 9 or 10 A. M., killed him and about 100 of his men, and captured several (Hough's "Northern Invasions " says 40 killed and two prisoners), and sent the survivors flying into van Rensselaer' s lines, to infect them with the terror of the slaughter from which they had just escaped. The Stone Arabia fight, in which Colonel Brown fell, was only two miles distant from the "Nose," where van Rensselaer's forces had already arrived. They heard the firing just as twilight was melting into night, in a valley where the latter prematurely reigned through the masses of smoke from burning buildings, which brooded like a black fog, sensible to the touch. Van Rensselaer came upon the position where Sir John had "settled " himself to resist. This "settled " is most apposite. It recalls a spectacle often visible in our woods, when a predatory hawk, wearied with his flight, settles on a limb to rest and resist a flock of encompassing furious crows, whose nests he has just invaded.

To refer back to the darkness occasioned by smoke, it may be necessary to state that the dwellers of cities or old cultivated districts have no conception of the atmospheric disturbance occasioned by extensive conflagrations in a wooded country.*

It is only lately that forest fires, commingled with fog, so obscured the atmosphere along the coast, to the eastward, that lamps and gas were necessary in the middle of the afternoon.

"What is more, the evening air in October is often heavy through a surcharge of dampness, especially along large streams and in bottom lands. To such as can imagine this condition of the atmosphere, it will at once become evident how much it was augmented immediately after a few volleys from about two thousand muskets, the smoke of the conflagrations, and the explosions of the powder, rendering objects invisible almost at arms' length. This is established by the testimony of a gallant American officer, Col.

* The dark day in Massachusetts, of 19th May, 1780, was due to this cause (Heath, 236-7-8), when artificial night, culminating about noon, sent the animal creation to roost and repose with less exceptions than during the completest eclipse, and filled the minds of men with apprehension and astonishment. This is not the only "dark day" so recorded. On the 25th October, 1820, at New York, candlelight was necessary at 11 A. M. The 16th May, 1780, was another "dark day" in Canada, where similar phenomena were observed on the 9th, 15th and 16th October, 1785. On the last, "it is said to have been as dark as a dark night." Several other instances are chronicled.

Dubois (Hough, 183-5), who stated that shortly after the firing became warm, when within five paces of his general, he could only recognize him by his voice. Therefore for anyone to pretend to relate what occurred within the lines of Sir John Johnson a few (15 ?) minutes after volleys had been exchanged along the whole fronts, is simply drawing upon the "imagination for facts." Consequently, when the American writers say that the enemy broke and ran, it was simply attributing to them what-was occurring within van Rensselaer's lines, where the officers could not restrain the rear from firing over and into the front, and from breaking beyond the power of being rallied. Doubtless, as always, the regulars on both sides behaved as well as circumstances permitted. Sir John's Indians, opposed to the American Continentals and Levies for the defence of the frontiers, it is very likely gave way almost at once. Brant, their gallant and able leader, was wounded in the heel, and therefore unable to move about, encourage them and hold them up to their work. Thus crippled he had enough to do to get off, for if taken he knew well that his shrift would be short and his "dispatch" speedy, if not "happy." Sir John was also struck in the thigh, and was charged with quitting the field. The only evidence of this is derived from one of his bitter personal enemies, surcharged with spite and a desire for vengeance. How bitterly he felt can be easily conceived, when he turned upon van Rensselaer and emphasized:-(Stone's "Brant," II., 124- 5, &c.) Colonel Stone remarks, "other accounts speak differently." (Ibid, II., 122.)

Gen. Sir Frederick Haldimand wrote to the home government that Sir John ''had destroyed the settlements of Schoharie and Stone Arabia, and laid waste a large extent of country," which was most true. It was added:

"He had several engagements with the enemy, in which he came off victorious. In one of them, near Stone Arabia, he killed a Col. Brown, a notorious and active rebel, with about one hundred officers and men." "I cannot finish without expressing to your Lordship the perfect satisfaction which I have from the zeal, spirit and activity with which Sir John Johnson has conducted this arduous enterprise.

Max von Eelking (II., 199-200), in his compilation of contemporaneous observations, presents the following testimony of the judgment and reliability of the superior, Gen. Haldimand, who reported, officially, in such flattering terms of the result of Sir John's expedition. He says of Haldimand that "he passed, according to English ideas, for one of the best and most trustworthy of British generals; had fought with distinction during the Seven Years' War in Germany. * * * He was a man strictly upright, kind-hearted and honorable. * * * Always of a character quite formal and punctilious as to etiquette, he was very fastidious in his intercourse, and did not easily make new acquaintances. * * * He required continual activity from his subordinates. * * * A Brunswick officer considers him one of the most worthy officers England has ever had. * * * This was about the character of the man to whom now the fate of the Canadas was entrusted by his Britannic Majesty."

It now seems a fitting time to consider the number of the opposing forces engaged. There has been a studied attempt to appreciate those present under Sir John and to depreciate those at the disposal of van Rensselaer. The same holds good with regard to the losses of the former; whereas the casualties suffered by the latter are studiously concealed. No two works agree in regard to the column led by Johnson. It has been estimated even as high as 1500, whereas a critical examination of its component parts demonstrates that it could not have comprised much more than a third of this number at the outset. As all Sir John's papers were lost in the Egyptian darkness of the night of the 19th October, it is necessary to fall back upon contemporaneous works for every detail.

The product of this calculation exactly agrees with the statement embodied in the testimony of Colonel Harper:

"The enemy's force was about 400 white men and but few Indians. The post from Albany, 18th October, reported that Sir John's party were "said to be about 500 men come down the Mohawk River." (Hough's "Northern Invasion," 122.)

When Sir John struck the Charlotte or Eastern Susquehanna he was joined by several hundred Indians. But a quarrel founded on jealousy-similar to such as was the curse of every aggregation of Scottish Highland tribes, even under Montrose, Claverhouse and the Pretender- soon after occurred, and several hundreds abandoned him.* (Simm's "Schoharie County", 399.)

Great stress has also been laid on Sir John's being provided with artillery. [The American general did have quite heavy guns for the period and locality, nine pounders.]

* The actual composition of Sir John Johnson's expeditionary column is well known, however often willfully misstated. He had three companies of his own Regiment of "Royal Greens," or "Loyal New Yorkers ;" one company of German-Jagers ; one company of British Regulars belonging to the Eighth (Major, afterwards Colonel A. S. de Peyster's) King's Regiment of Foot, which performed duty by detachments all along the frontier from Montreal to the farthest west, and in very raid and hostile movement-besides detachments-a company or platoon from the Twentieth, and (?) also from the Thirty-fourth British Infantry, and a detachment-sometimes rated by the Americans as high as two hundred men-from Butler's Loyalist or Tory Rangers. Sir John in his reports of casualties' mentions these all, except the Twentieth Regiment, and no others. Figure this up, and take sixty as a fair allowance for the numerical force of a company, which is too large an allowance, basing it on the average strength of British regiments which had seen active service for any length of time on this continent, and six times sixty makes three hundred and sixty, plus two hundred, gives five hundred and sixty. Deduct a fair percentage for the footsore and other casualties inseparable from such service, and it reduces his whites down to exactly what Colonel Harper states was reported to him by an Indian as being at Klock's Field.

Colonel W. L. Stone ("Brant," II., 105) specifies three companies of Sir John's own Regiment of Greens, one company of German Jagers, a detachment of two hundred men (doubtful authority cited) from Butler's Rangers, and one (only one) company of British Regulars. The Indian portion of this expedition was chiefly collected under Brant at Tioga Point, on the Susquehanna, which they ascended to Unadilla. Stone's language, "besides Mohawks," is ambiguous. Sir John had few Indians left-as was usually the case with these savages-when they had "to face the music."

Governor Clinton (Hough's " Northern Invasion," 154) estimates Sir John's force at seven hundred and fifty picked troops and Indians. Very few Indians were in the fight of the 19th October, p. M. Other corroborations have already been adduced. Simm's ("Schoharie County," 399) says that Sir John left Niagara with about five hundred British, Royalist and German troops, and was joined by a large body of Indians and Tories under Captain Brant, on the Susquehanna, making his effective (Continued)

Close study exploded this fantasy likewise. That he he had several pieces of extremely light artillery, hardly deserving the name, with him as far as Chittenango

force, " as estimated at the several forts," one thousand men. If this estimate is credited to the several forts who were "panicky," the condition of their vision renders its correctness unworthy of acceptance. He then goes on to say that several hundred Indians deserted.

The strength of regiments varied from three hundred and under to six hundred and fifty. It is well known that some American regiments scarcely rose above one hundred rank and file. It is almost unanimously conceded that Harkheimer had at least four regiments-if not five-the whole comprising only eight or nine hundred men, at Oriskany. This does not include volunteers, Indians, &c., &c.

General van Rensselaer, judging from the testimony given before the Court of Enquiry, and his own letters (Simms, 425, &c.), had seven to nine hundred militia when he reached Schenectady. It is very hard to calculate his ultimate aggregate of militia. He had at first his own Claverack Brigade. The City of Albany Militia and some other Regimerits had preceded him. Colonel Van Alstyne's Regiment joined him by another route. How did Colonel Cuyler's Albany Regiment come up ? Colonel Clyde reinforced him with the Canajoharie District Regiment (Tryon County, for military purposes, was divided into Districts, each of which furnished its quota), likewise (Simm's, 425) "the Schoharie Militia" " near Fort Hunter." This dissection might be followed out further to magnify the American force, and show against what tremendous odds Sir John presented an undaunted front, and what numbers he shocked, repulsed and foiled. Van Rensselaer was afterwards joined by the Continental Infantry, under Colonel Morgan Lewis; the New York quasi-regulars or Levies, three or four hundred, under Colonel Dubois ; McKean's Volunteers, sixty; the Indians under Colonel Louis, sixty; John Ostrom, a soldier present, adds (Simm's " Schoharie County," 424) two hundred Indians under Colonel Harper, the Artillery and the Horse. The Militia of Albany County were organized into seventeen regiments; of Charlotte County into one; of Tryon County into five ; besides these there were other troops at hand under different names and peculiarities of service. It is certain that all the Militia of Albany, Charlotte and Tryon Counties, and every other organization that were accessible, were hurried to meet Sir John, and severe Clinton was not the man to brook shirking. Twenty-three regiments of Militia must have produced twenty-four hundred men-a ridiculously small figure. Add the other troops known to be with van "Rensselaer, and he faced the Loyal leader with five or six times as many as the latter had ; or else the Claverack Brigadier had with him only a startling redundancy of field officers and a disgraceful deficiency of rank and file.

Creek is true (Hammond's "Madison County," 656). Two of these he sunk intentionally in this stream, or else they went to its bottom accidentally. Thence he carried on two little four and three-quarter pounder mortars, probably "Royals," and a grasshopper three-pounder. As our armies were well acquainted with the improved Cohorns used at the siege of Petersburg, it is unnecessary to explain that they were utterly impotent against stone buildings, or even those constructed of heavy logs. The Cohorns of 1780 were just what St. Leger reported of them in 1777-that they were good for "teasing," and nothing more. Even one of these Sir John submerged in a marsh after his attempt upon the Middle Fort, now Middleburg. Clinton (157) wrote that both were ''concealed [abandoned] by the Loyalists on their route from Schoharie."

Most likely it was an impediment. And nothing is afterwards mentioned of the use of the other. The "grasshopper" three-pounder derived its name from the fact that it was not mounted upon wheels, but upon iron legs. It was one of those almost useless little guns which were transported on bat-horses, just as twelve-pounder mountain howitzers are still carried on pack animals. As Sir John's horses, draught and beef cattle, appear to have been stampeded in the confusion of the intense darkness; almost everything which was not upon his soldier's persons, or had not been sent forward when he "settled" at Klock's Field to check pursuit, liad to be left when he drew off. The darkness of the night, as stated, was Intensified by the powder smoke and smoke of burning buildings, and the bottom fog which filled the whole valley. Under such circumstances small objects could not be recovered in the hurry of a march.

The Americans made a great flourish over the capture of Sir John's artillery. The original report was comparatively lengthy, but simply covered the little "grasshopper," fifty-three rounds of ammunition, and a few necessary implements and equipments for a piece, the whole susceptible of transport on two packsaddles. Most probably the bat-horses were shot or disabled or- "run off" in the melee.

It is even more difficult to arrive at van Rensselaer's numbers. The lowest figure when at Schenectady is seven hundred. This perhaps indicated his own Claverack (now Columbia County) Brigade. He received several accessions of force, Tryon and Albany County militia ; the different colonels and their regiments are especially mentioned, besides the quasi-regular command-three or four hundred (Hough, one hundred and fifty)-of Colonel Dubois' Levies raised and expressly maintained for the defence of the New York Northern Frontier ; Captain M'Kean's eighty Independent Volunteers ; sixty to one hundred Indians, Oneida warriors, under Colonel Louis : a detachment of regular Infantry under Colonel Morgan Lewis, who led the advance (Stone's "Brant," II., 120): a company or detachment of artillery and two nine-pounders, and a body of horsemen.

Colonel Stone, writing previous to 1838, says: "The command of General van Rensselaer numbered about fifteen hundred-a force in every way superior to that of the enemy." It is very probable that he had over two thousand, if not many more than this. Stone adds ("Brant, "II., 119): " Sir John's troops, moreover, were exhausted by forced marches, active service, and heavy knapsacks, while those of van Rensselaer were fresh in the field." Sir John's troops had good reason to be exhausted. Besides their march from Canaseraga, one hundred and fifty miles, they had been moving, destroying and fighting constantly for three or four days, covering in this exhaustive work a distance of over seventy-five (twenty-six miles straight) miles in the Mohawk Y alley alone (Hough, 152). On the very day of the main engagement they had wasted the whole district of Stone Arabia, destroyed Brown's command in a spirited attempt to hold the invaders, and actually advanced to meet van Rensselaer by the light of the conflagrations they kindled as they marched along. Each British and Loyal soldier carried eighty rounds of ammunition, which, together with his heavy arms, equipments, rations and plunder, must have weighed one hundred pounds and upwards per man. van Rensselaer's Militia complained of fatigue; but when did this sort of troops ever march even the shortest testing distance without grumbling?

The Americans figured out Sir John's loss at 9 killed, 7 wounded, and 53 missing. His report to General Haldimand states that throughout his whole expedition he lost in killed, whites and Indians, 9; wounded, 7; and missing, 48, which must have included the wounded who had to he abandoned ; and desertions, 3 ; the last item is the most remarkable in its significance and insignificance. (Hough's "Northern Invasion," 136.)

How the troops on either side were drawn up for the fight appears to have been pretty well settled, for there was still light enough to make this out, if no more. Sir John's line extended from the river to the orchard near Klock's house. His Hangers-Loyalists-were on the right, with their right on the bank of the Mohawk. His regular troops stood in column in the center on the Flats. Brant's Indians and the Hesse-Hanau Riflemen or Jagers were on the left, in echelon, in advance of the rest about one hundred and fifty yards, in the orchard. Van Rensselaer's forces were disposed: Colonel Dubois with the Levies (quasi-regulars) on the right, Whites and Indians constituting the central column, and the Albany Militia on the left. [Simm's " Schoharie County," 430.) Not a single witness shows where the Continentals, Artillerymen and the Horsemen took position. As for the two nine-pounder fieldpieces, they were left behind, stuck in the mud. It was a tohu-bohu. The regulars on both sides behaved well, as they almost always do. With the first shots the militia began to fire-Cuyler's Regiment, four hundred yards away from the enemy-the rear rank ran over and into those in front, two hundred and fifty to three hundred yards in advance (193), then broke ; all was confusion. It does not appear that the American Indians accomplished anything. Colonel Dubois' New York Levies ran out Brant's Indians, and got in the rear of Sir John's line, and then there was an end of the matter. (Simm's "Schoharie County," 429-30.) It had become so dark from various causes that, to use a common expression, "a man could not see his hand before his face."

Van Rensselaer had now enough to do to keep the majority of his troops together, and retreated from one and a half to three miles, to a cleared hill, where, he was enabled to restore some order. The stories of disorder within Sir John's lines, except as regarded the Indians, are all founded on unreliable data; nothing is known. When his antagonist fell back, he waited apparently until the moon rose, and then, or previously, forded the river (just above Nathan Christie's-(Simms, 430)-and commenced his retreat, which he was permitted to continue unmolested.

It is amusing to read the remarks and reasoning of patriotic imagination on this event. "By this time," says the Sexagenary, " however, the alarm had spread through the neighboring settlements, and a body of militia, of sufficient force to become the assailants, arrived, it is said, within a short distance of the enemy, near the river, and Sir John Johnson, in consequence, had actually made arrangements to surrender." [Mark the logical military conclusion, Sir John being ready to surrender!] The Americans, however, at this moment fell tack a short distance [two or three miles] for the sake of occupying a better position during the night. If Sir John was scared and willing to give up, what need was there of the brave Americans falling back at all, or seeking a better position? All they had to do was to go forward, disarm the willing prisoners, and gather in the trophies. He had fought a Cumberland Church fight to check pursuit, and there was no Humphreys present to renew it and press on to an Appomattox Court House. He had accomplished his task; he had completed the work of destruction in the Schoharie and Mohawk valleys. There was nothing more to be wasted. Colonel Stone sums it up thus ("Brant," II., 124) : "By this third and most formidable irruption into the Mohawk country during the season, Sir John had completed the entire destruction above Schenectady-the principal settlement above the Little Falls having been sacked and burned two years before." French observed that these incursions left "the remaining citizens stripped of almost everything except the soil."*

* The forces of Colonel [Sir John] Johnson, a part of which had crossed the river near Caughnawaga, destroyed all the Whig property, not only on the south, but on the north side, from Fort Hunter to the [Anthony's N. T. 60] Nose (some twenty-three to twenty-five miles), and in several instances where dwellings had been burned by the Indians under his command in May (1780), and temporary ones rebuilt, they were also consumed. * * * After Brown fell, the enemy, scattered in small bodies, were to be seen in every direction plundering and burning the settlements in Stone Arabia. In the afternoon General van Rensselaer, after being warmly censured for his delay by Col. Harper and several other officers, crossed the river at Fort Plain, and began the pursuit in earnest. The enemy were overtaken [awaited him] on the side of the river above St. Johnsville, near a stockade and blockhouse at Klock's, just before night, and a smart brush took place between the British troops and the Americans under Col. Dubois in

The most curious thing in this connection is the part played by the fiery Governor Clinton. Colonel Stone expressly stated, in 1838, that he was with General van Rensselaer

which several on each side were killed or -wounded. Johnson was compelled to retreat to a peninsula in the river, where he encamped with his men much wearied. His situation was such that he could have been taken with ease. Col. Dubois, with a body of Levies, took a station above him to prevent his proceeding up the river; Gen. van Rensselaer, with the main army, below ; while Col. Harper, with the Oneida Indians, gained a position on the south side of the river nearly opposite. [Why did they not guard the ford by which Sir John crossed? They were afraid of him, and glad to let him go if he only would go away.] The general gave express orders that the attack should be renewed by the troops under his own immediate command at the rising of the [full (between 10 and 11 P. M.?) (H. N. I. 55) ] moon, some hour in the night. Instead, however, of encamping on the ground from which the enemy had been driven, as a brave officer would have done, he fell back down the river and encamped THREE MILES distant. The troops under Dubois and Harper could hardly be restrained from commencing the attack long before the moon arose ; but when it did, they waited with almost breathless anxiety to hear the rattle of van Rensselaer's musketry. The enemy, who encamped on lands owned by the late Judge Jacob G. Klock, spiked their cannon [the diminutive three-pounder grasshopper was all they had], which was there abandoned; and, soon after the moon appeared, began to move forward to a fording place just above the residence of Nathan, Christie, and not far from their encampment. Many were the denunciations made by the men under Dubois and Harper against Van Rensselaer, when they found he did not begin the attack, and had given strict orders that their commanders should not. They openly stigmatized the general * * * but, when several hours had elapsed, and he had not yet made his appearance, a murmur of discontent pervaded all. Harper and Dubois were compelled to see the troops under Johnson and Brant ford the river, and pass off unmolested, or disobey the orders of their commander, when they could, unaided, have given them most advantageous battle. Had those brave colonels, at the moment the enemy were in the river, taken the responsibility of disobeying their commander, as Murphy had done three days before, and commenced the attack in front and rear, the consequences must have been very fatal to the retreating army, and the death of Col. Brown and his men promptly revenged. Jacob Becker, a Schoharie Militiaman. 428-430 Jeptha R. Simm's "History of schoharie County," 1845.

a few hours before the fight, dined with him at Fort Plain, and remained at the Fort when van Rensselaer marched out to the fight. In Col. Stone's, or his son and namesake's, "Border Wars " (II., 122), this statement is repeated. Clinton, in one of his letters, dated 30th October, does not make the matter clear. He says (Hough, 151): "On receiving this intelligence [the movements of the British] I immediately moved up the river, in hopes of being able to gain their front, &c." In describing the engagement he says, "the night came on too soon for us" and then afterwards he mentions "the morning after the action I arrived with the militia under my immediate command." This does not disprove Stone's account. Aid-Major Lansing testified before the court-martial that the Governor took command on the morning of the 21st. It is not likely that Governor Clinton would have found it pleasant to fall into the hands of Sir John, and Sir John would have been in a decidedly disagreeable position if the Governor could have laid hands upon him. There was this difference, however; Sir John was in the fight (Colonel Dubois wrote 11 A. M., the day after the fight -- Hough's "Northern Invasion," 118). Prisoners say Sir John was wounded through the thigh) which he might have avoided; and the Governor might have been. Anyone who will consider the matter dispassionately will perceive that, now that the whole country was aroused, and all the able-bodied males, regulars and militia, concentrating upon him, Sir John had simply to look to the safety of his command. He retreated by a route parallel to the Mohawk River and to the south of it, passed the Oneida Castle on the creek of the same name, the present boundary between Madison and Oneida Counties, and made for Canaseraga, where he had left his batteaux. Meanwhile van Rensselaer had dispatched an express to Fort Schuyler or Stanwix, now Rome, ordering Captain Vrooman, with a strong detachment from the garrison, to push on ahead as quickly as possible and destroy Sir John's little flotilla. A deserter frustrated Burgoyne's last and best chance to escape. Two Oneida Indians, always unreliable in this war, revealed the approach of Sir John, and by alarming saved the forts in the Schoharie valley. And now another such chance enabled Sir John to save his boats and punish the attempt made to destroy them. One of Captain Vrooman's men fell sick, or pretended to fall sick, at Oneida Castle ("Hist. Madison Co.," 656, &c.), and was left behind. Soon after, Sir John arrived, and learned from the invalid the whole plan. Thereupon he sent forward Brant and his Indians, with a detachment of Butler's Rangers, who came upon Vrooman's detachment taking their midday meal, 23d November, 1780, and "gobbled" the whole party. Not a shot was fired, and Captain Vrooman and his men were carried off prisoners in the very boats they were dispatched to destroy.

If any reader supposes that this invasion of Sir John Johnson's was a simple predatory expedition, he has been kept in ignorance of the truth through the idiosyncrasies of American writers. It was their purpose to malign Sir John, and they have admirably succeeded in doing so. Sir John Johnson's expedition was a part of a grand strategic plan, based upon the topography of the country, which rendered certain lines of operation inevitable. Ever since the English built a fort at Oswego, as a menace to the French then in possession of Canada, this port and Niagara were bases for hostile movements against Canada. Pitt's great plan, the conquest of New France in 1759, contemplated a triple attack: down Lake Champlain, across from Oswego, and up the St. Lawrence. The Burgoyne campaign in 1777 was predicated on the same idea: Burgoyne up Champlain,- St. Leger from Oswego down the Mohawk, and Howe up the Hudson. Clinton's plan for the fall of 1780 was almost identical, although everything hinged on the success of Arnold's treason and his delivering up West Point. Clinton himself was to play the part Howe should have done and ascend the Hudson. Colonel Carleton was to imitate Burgoyne on a smaller scale, and move up Champlain to attract attention in that direction; and Sir John was to repeat the St. Leger movement of 1T77, and invade the Mohawk valley. Arnold's failure frustrated Clinton's movement. Carleton at best was to demonstrate, because the ambiguity (or consistent self-seeking) of Vermont rendered a more numerous column unnecessary. As it was, he penetrated to the Hudson, and took Fort Anne. Haldimand's nervousness about a French attack upon Canada made him timid about detaching a sufficient force with Sir John. Moreover, the British regulars were very unwilling to accompany this bold partisan, whose energy insured enormous hardship, labor and suffering to his followers, to which regulars, more particularly German mercenaries, were especially averse. Von Eelking informs us of this, and furthermore that a terrible mutiny came very near breaking out among the British troops under Johnson in the succeeding June, when Haldimand proposed to send Sir John on another expedition against Pittsburg. The plan of the mutineers (von Eelking, II., 197) was to fall upon the British officers in their quarters and murder them all. The complot was discovered, but it was politic to hush the whole matter up, which was accordingly done. Doubtless there was hanging or shooting and punishment enough, but it was inflicted quietly. These were the reasons that the invasion which was to have been headed by Sir John Johnson was converted into a destructive raid, and this explains why Sir John was so weak-handed that he could not dispose of van Rensselaer on Klock' s Field as completely as he annihilated Brown in Stone Arabia.

Finally, to divest Sir John Johnson's expedition of the character of a mere raid, it is only necessary to compare some dates. Arnold's negotiations with Sir Henry Clinton came to a head about the middle of September. It was not settled until the 21st-22d of that month. It is not consistent with probability that Haldimand in Canada was ignorant that a combined movement was contemplated. To justify this conclusion, von Eelking states (II., 195) that three expeditions, with distant objectives, started from Quebec about the "middle of September,"-the very time when Clinton and Arnold were concluding their bargain;- the first, under Sir John Johnson, into the Schoharie and Mohawk vallies; the second, under Major Carleton, which took Forts Anne and George, towards Albany; and the third, under Colonel Carleton, reversing the direction of the route followed by Arnold in 1775.

The time necessary to bring Sir John into middle New York, making due allowances for obstacles, was about coincident with the date calculated for the surrender of West Point. Arnold made his escape on the 25th of September. Andre was arrested on the 23d of September, and was executed on the 2d of October following. Major Carleton came up Lake Champlain, and appeared before Fort Anne oh the 10th of October (Hough's "Northern Invasion," I., 43), Major Houghton (Ibid, 146) simultaneously fell upon the upper settlements of the Connecticut Valley; and Major Munro, a Loyalist, started with the intention-it is believed-of surprising Schenectady; but, for reasons now unknown, stopped short at Ballston, attacked this settlement on midnight of the 16th of October, and then retired, carrying off a number of prisoners. Such a coincidence of concentrating attacks from four or five different quarters by as many different routes could not have been the result of accident. Circumstances indicate that Sir Henry Clinton was first to move in force upon West Point, and make himself master of it through the treasonable dispositions of Arnold. This would have riveted the attention of the whole country. Troops would have been hurried from all quarters towards the Highlands, and the whole territory around Albany denuded of defenders. Thus it was expected that Sir John would have solved the problem which St. Leger failed to do in 1777. Meanwhile, the Carletons, certain of the neutrality of Vermont, whose hostilities had been so effective in 1777, would have captured all the posts on the upper Hudson. In this way the great plan, which failed in 1777, was to be accomplished in 1780. Thousands of timid Loyalists would have sprung to arms to support Sir John and Clinton, and the severance of the Eastern from the Middle States completed, and perfect communication established between New York and Montreal. It would have taken but very little time for Clinton to double his force from Loyal elements along the whole course of the Hudson, as can be demonstrated from records, admissions and letters of the times. The majority of the people were tired of the war, and even Washington despaired. On the 17th October, 1780, Governor Clinton wrote to General Washington: "This enterprise of the enemy [Sir John Johnson] is probably the effect of Arnold's treason." On the 21st of the same month General Washington, addressing the President of the Continental Congress, wrote : "It is thought and perhaps not without foundation, that this incursion was made [by Sir John Johnson] upon the supposition that Arnold's treachery had succeeded."

If Arnold's treason had not been discovered in time, the name of Sir John Johnson might stand to-day in history in the same class beside that of Wolfe, instead of being branded as it has been by virulence, and worse, in many cases, by direct misrepresentation.

"Success is the test of merit," said the unfortunate Rebel General Albert Sydney Johnson--"a hard rule," he added, "but a just one." It is both hard and unjust, and were courage, merit, self-devotion and exposure to suffering and peril the test, and not success, there are few men who would stand higher today in military annals than Sir John Johnson.