"The sun has drunk

The dew that lay upon the morning grass;

There is no rustling in the lofty elm

That canopies my dwelling, and its shade

Scarce cools me. All is silent save the faint

And interrupted murmur of the bee,

Sitting on the sick flowers, and then again

Instantly on the wing. The plants around

Feel the too potent fervors; the tall maize

Rolls up its long green leaves; the clover droops

Its tender foliage, and declines its blooms.

But far in the fierce sunshine tower the hills,

With all their growth of woods, silent and stern,

As if the scorching heat and dazzling light

Were but an element they loved."

BRYANT.

IT was early in the morning of such a day as the poet refers to that we commenced a ride and a ramble over the historic grounds of Saratoga near Schuylerville, accompanied by the friendly guide whose proffered services I have already mentioned. We first rode to the residence of Mrs. J -- n, one of the almost centenarian representatives of the generation cotemporary with our Revolution, now so few and hoary. She was in her ninety-second year of life, yet her mental faculties were quite vigorous, and she related her sad experience of the trials of that war with a memory remarkably tenacious and correct. Her sight and hearing were defective, and her skin wrinkled; but in her soft blue eye, regular features, and delicate form were lingering many traces of the beauty of her early womanhood. She was a young lady of twenty years when Independence, was declared, and was living with her parents at Do-ve-gat (Coveville) when Burgoyne came down the valley. She was then betrothed, but her lover had shouldered his musket, and was in Schuyler's camp.

While Burgoyne was pressing onward toward Fort Edward from Skenesborough, the people of the valley below, who were attached to the patriot cause, fled hastily to Albany. Mrs. J-n and her parents were among the fugitives. So fearful were they of the Indian scouts sent forward, and of the resident Tories, not a whit less savage, who were emboldened by the proximity of the invader, that for several nights previous to their flight they slept in a swamp, apprehending that their dwelling would be burned over their heads or that murder would break in upon their repose. And when they returned home, after the surrender of Burgoyne, all was desolation. Tears filled her eyes when she spoke of that sad return. "We had but little to come home to," she said. "Our crops and our cattle, our sheep, hogs, and horses, were all gone, yet we knelt down in our desolate room and thanked God sincerely that our house and barns were not destroyed." She wedded her soldier soon afterward, and during the long widowhood of her evening of life his pension has been secured to her, and a few years ago it was increased in amount. She referred to it, and with quivering lip-quivering with the emotions of her full heart-said, "The government has been very kind to me in my poverty and old age." She was personally acquainted with General Schuyler, and spoke feelingly of the noble-heartedness of himself and lady in all the relations of life. While pressing her hand in bidding her farewell, the thought occurred that we

89

represented the linking of the living, vigorous, active present, and the half-buried, decaying past; and that between her early womanhood and now all the grandeur and glory of our Republic had dawned and brightened into perfect day.

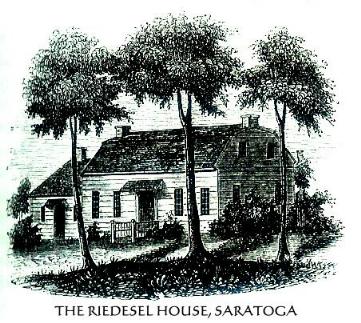

From Mrs. J-n's we rode to the residence of her brother, the house wherein the Baroness Riedesel, with her children and female companions, was sheltered just before the surrender of Burgoyne. It is about a mile above Schuylerville, and nearly opposite the mouth of the Batten Kill. On our way we paused to view the remains of the fortifications of Burgoyne's camp, upon the heights a little west of the village. Prominent traces of the mounds and ditches are there visible in the woods. A little northwest of the village the lines of the defenses thrown up by the Germans, and Hessians of Hanau may be distinctly seen. (See map, page 77.)

The

house made memorable by the presence and the pen of the wife of the Brunswick

general is well preserved. At the time of the Revolution it was owned by

Peter Lansing, a relative of the chancellor of that name, and now belongs

to Mr. Samuel Marshall, who has the good taste to keep up its original character.

It is upon the high bank west of the road from Schuylerville to Fort Miller,

pleasantly shaded in front by locusts, and fairly embowered in shrubbery

and fruit trees.

The

house made memorable by the presence and the pen of the wife of the Brunswick

general is well preserved. At the time of the Revolution it was owned by

Peter Lansing, a relative of the chancellor of that name, and now belongs

to Mr. Samuel Marshall, who has the good taste to keep up its original character.

It is upon the high bank west of the road from Schuylerville to Fort Miller,

pleasantly shaded in front by locusts, and fairly embowered in shrubbery

and fruit trees.

We will listen to the story of the sufferings of some of the women of Burgoyne's camp in that house, as told by the baroness herself: "About two o'clock in the afternoon we again heard a firing of cannon and small arms; instantly all was alarm, and every thing in motion. My husband told me to go to a house not far off. I immediately seated myself in my caleche, with my children, and drove off; but scarcely had we reached it before I discovered five or six armed men on the other side of the Hudson. Instinctively I threw my children down in the caleche, and then concealed myself with them, At this moment the fellows fired, and wounded an already wounded English soldier, who was behind me. Poor fellow! I pitied him exceedingly, but at this moment had no power to relieve him.

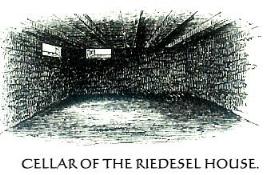

"A terrible cannonade was commenced by the enemy against the house

in which I sought to obtain  shelter

for myself and children, under the mistaken idea that all the generals were

in it. Alas! it contained none but wounded and women. We were at last obliged

to resort to the cellar for refuge, and in one corner of this I remained

the whole day, my children sleeping on the earth with their heads in my

lap; and in the same situation I passed a sleepless night.(1) Eleven cannon-balls

passed through the house, and we could distinctly hear them roll away. One

poor soldier, who was lying on a table for the purpose of having his leg

amputated, was struck by a shot, which carried away his other; his comrades

had left him, and when we went to his assistance we found him in a corner

of the room, into which he had crept, more dead than alive, scarcely breathing.(2)

My reflections on the danger to which my husband was exposed now agonized

me exceedingly, and the thoughts of my children, and the necessity of struggling

for their preservation, alone sustained me.

shelter

for myself and children, under the mistaken idea that all the generals were

in it. Alas! it contained none but wounded and women. We were at last obliged

to resort to the cellar for refuge, and in one corner of this I remained

the whole day, my children sleeping on the earth with their heads in my

lap; and in the same situation I passed a sleepless night.(1) Eleven cannon-balls

passed through the house, and we could distinctly hear them roll away. One

poor soldier, who was lying on a table for the purpose of having his leg

amputated, was struck by a shot, which carried away his other; his comrades

had left him, and when we went to his assistance we found him in a corner

of the room, into which he had crept, more dead than alive, scarcely breathing.(2)

My reflections on the danger to which my husband was exposed now agonized

me exceedingly, and the thoughts of my children, and the necessity of struggling

for their preservation, alone sustained me.

1 The cellar is about fifteen by thirty feet in size, and

lighted and ventilated by two small windows only.

2 The place where this ball entered is seen under the window near the corner,

and designated in the picture by a small black spot. (lower right side)

90

"The ladies of the army who were with me were Mrs. Harnage, a Mrs. Kennels the widow of a lieutenant who was killed, and the lady of the commissary. Major Harnage, his wife, and Mrs. Kennels made a little room in a corner with curtains to it, and wished to do the same for me, but I preferred being near the door, in case of fire. Not far off my women slept, and opposite to us three English officers, who, though wounded, were determined not to be left behind; one of them was Captain Green, an aid-de-camp to Major-general Phillips, a very valuable officer and most agreeable man. They each made me a most sacred promise not to leave me behind, and, in case of sudden retreat, that they would each of them take one of my children on his horse; and for myself one of my husband's was in constant readiness. . . . . . . . The want of water distressed us much; at length we found a soldier's wife who had courage enough to fetch us some from the river, an office nobody else would undertake, as the Americans shot at every person who approached it; but, out of respect for her sex, they never molested her.

"I now occupied myself through the day in attending the wounded; I made them tea and coffee, and often shared my dinner with them, for which they offered me a thousand expressions of gratitude. One day a Canadian officer came to our cellar, who had scarcely the power of holding himself upright, and we concluded he was dying for want of nourishment; I was happy in offering him my dinner, which strengthened him, and procured me his friendship. I now undertook the care of Major Bloomfield, another aid-de-camp of General Phillips; he had received a musket-ball through both cheeks, which in its course had knocked out several of his teeth and cut his tongue; he could hold nothing in his mouth, the matter which ran from his wound almost choked him, and he was not able to take any nourishment except a little soup or something liquid. We had some Rhenish wine, and, in the hope that the acidity of it would cleanse his wound, I gave him a bottle of it. He took a little now and then, and with such effect that his cure soon followed; thus I added another to my stock of friends, and derived a satisfaction which, in the midst of sufferings. served to tranquilize me and diminish their acuteness.

"One day General Phillips accompanied my husband, at the risk of their lives, on a visit to us. The general, after having beheld our situation, said to him, 'I would not for ten thousand guineas come again to this place; my heart is almost broken.'

"In this horrid situation we remained six days; a cessation of hostilities was now spoken of, and eventually took place."

The baroness, in the simple language of her narrative, thus bears testimony to the generous courtesy of the American officers, and to the true nobility of character of General Schuyler in particular: "My husband sent a message to me to come over to him with my children. I seated myself once more in my dear caleche, and then rode through the American camp. As I passed on I observed, and this was a great consolation to me, that no one eyed me with looks of resentment, but they all greeted us, and even showed compassion in their countenances at the sight of a woman with small children I was, I confess, afraid to go over to the enemy, as it was quite a new situation to me. When I drew near the tents a handsome man approached and met me, took my children from the caleche, and hugged and kissed them, which affected me almost to tears. 'You tremble,' said he, addressing himself to me; 'be not afraid.' 'No,' I answered, 'you seem so kind and tender to my children, it inspires me with courage.' He now led me to the tent of General Gates, where I found Generals Burgoyne and Phillips, who were on a friendly footing with the former. Burgoyne said to me, 'Never mind; your sorrows have now an end.' I answered him that I should be reprehensible to have any cares, as he had none; and I was pleased to see him on such friendly footing with General Gates. All the generals remained to dine with General Gates.

"The same gentleman who received me so kindly now came and said to me, 'Yon will be very much embarrassed to eat with all these gentlemen; come with your children to my tent, where I will prepare for you a frugal dinner, and give it with a free will.' I said, 'You are certainly a husband and a father, you have shown me so much kindness.'

91

I now found that he was General Schuyler. He treated me with excellent smoked tongue,

beef-steaks, potatoes, and good bread and butter! Never could I have wIshed to eat a better dinner; I was content; I saw all around me were so likewise; and, what was better than all, my husband was out of danger.

"When we had dined he told me his residence was at Albany, and that General Burgoyne intended to honor him as his guest, and invited myself and children to do so likewise. I asked my husband how I should act; he told me to accept the invitation. As it was two days' journey there, he advised me to go to a place which was about three hours' ride distant.

"Some days after this we arrived at Albany, where we so often wished ourselves; but we did not enter it as we expected we should-victors!(1) We were received by the good General Schuyler, his wife, and daughters, not as enemies, but kind friends; and they treated us with the most marked attention and politeness, as they did General Burgoyne, who had caused General Schuyler's beautifully-finished house to be burned. In fact, they behaved like persons of exalted minds, who determined to bury all recollections of their own injuries in the contemplation of our misfortunes. General Burgoyne was struck with General Schuyler's generosity, and said to him, 'You show me great kindness, though I have done you much injury.' 'That was the fate of war,' replied the brave man; 'let us say no more about it.' "

General Schuyler was detained at Saratoga when Burgoyne and suite started for Albany.

1 General Burgoyne boasted at Fort Edward that he should eat a Christmas dinner in Albany, surrounded by his victorious army.

92

He wrote to his wife to give the English general the very best reception in her power, " The British commander was well received," says the Marquis de Chastellux,(1) in his Travels in America, "by Mrs. Schuyler, and lodged in the best apartment in the house. An excellent supper was served him in the evening, the honors of which were done with so much grace that he was affected even to tears, and said, with a deep sigh, 'Indeed, this is doing too much for the man who has ravaged their lands and burned their dwellings.' The next morning he was reminded of his misfortunes by an incident that would have amused any one else. His bed was prepared in a large room; but as he had a numerous suite, or family, several mattresses were spread on the floor for some officers to sleep near him. Schuyler's second son, a little fellow about seven years old, very arch and forward, but very amiable, was running all the morning about the house. Opening the door of the saloon, he burst out a laughing on seeing all the English collected, and shut it after him, exclaiming, 'You are all my prisoners !' This innocent cruelty rendered them more melancholy than before."

We next visited the headquarters of General Gates, south of the Fish Creek, delineated on page 75. On our way we passed the spot, a few rods south of the creek, where Lovelace, a prominent Tory, was hung. It is upon the high bluff seen on the right of the road in the annexed sketch, which was taken from the lawn in front of the rebuilt mansion of General Schuyler.

Lovelace was a fair type of his class, the bitterest and most implacable

foes of the republicans. There

were many Tories who were so from principle, and refused to take sides against

the parent country from honest convictions of the wrongfulness of such a

course. They looked upon the Whigs as rebels against their sovereign; condemned

the war as unnatural, and regarded the final result as surely disastrous

to those who had lifted up the arm of opposition. Their opinions were courteously

but firmly expressed; they took every opportunity to dissuade their friends

and neighbors from participation in the rebellion; and by all their words

and acts discouraged the insurgent movement. But they shouldered no musket,

girded on no sword, piloted no secret expedition against the republicans.

They were passive, noble minded men, and deserve our respect for their consistency

and our commiseration for their sufferings at the hands of those who made

no distinction between the man of honest opinions and the marauder with

no opinions at all.

There was another class of Tories, governed by the footpad's axiom, that "might makes right." They were Whigs when royal power was weak, and Tories when royal power was strong. Their god was mammon, and they offered up human sacrifices in abundance upon its altars. Cupidity and its concomitant vices governed all their acts, and the bonds of consanguinity and affection were too weak to restrain their fostered barbarism. Those born in the same neighborhood; educated (if at all) in the same school; admonished, it may be, by the same pastor, seemed to have their hearts suddenly closed to every feeling of friendship or of love, and became as relentless robbers and murderers of neighbors and friends as the savages of the wilderness. Of this class was Thomas Lovelace, who, for a time, became a terror to his old neighbors and friends in Saratoga, his native district.

At the commencement of the war Lovelace went to Canada, and there confederated with five other persons from his own county to come down into Saratoga and abduct, plunder, or betray their former neighbors. He was brave, expert, and cautious. His quarters were in a large swamp about five miles from the residence of Colonel Van Vechten at Do-ve-gat, but his place of rendezvous was cunningly concealed. Robberies were frequent, and several inhabitants were carried off. General Schuyler's house was robbed, and an attempt was

1 A French officer, who served in the army in this country during a part of the Revolution.

93

made by Lovelace and his companions to carry off Colonel Van Vechten; but the active vigilance of General Stark, then in command of the barracks north of the Fish Creek,(1) in furnishing the colonel with a guard, frustrated the marauder's plans. Intimations of his intentions and of his place of concealment were given to Captain Dunham, who commanded a company of militia in the neighborhood, and he at once summoned his lieutenant, ensign, orderly, and one private to his house(2) At dark they proceeded to the "Big Swamp," three miles distant, where two Tory families resided. They separated to reconnoiter, but two of them, Green and Guiles, were lost. The other three kept together, and at dawn discovered Lovelace and his party in a hut covered over with boughs, just drawing on their stockings. The three Americans crawled cautiously forward till near the hut, when they sprang upon a log with a shout, leveled their muskets, and Dunham exclaimed, "Surrender, or you are all dead men !" There was no time for parley, and, believing that the Americans were upon them in force, they came out one by one without arms, and were marched by their captors to General Stark at the barracks. They were tried by a court-martial as spies, traitors, and robbers, and Lovelace, who was considered too dangerous to be allowed to escape, was sentenced to be hung. He complained of injustice, and claimed the leniency due to a prisoner of war; but his plea was disallowed, and three days afterward he was hung upon the brow of the hill at the place delineated, during a tremendous storm of rain and wind, accompanied by vivid lightning and clashing thunder-peals. These facts were communicated to me by the son of Colonel Van Vechten, who accompanied me to the spot, and who was well acquainted with all the captors of Lovelace and his accomplices.

The place where Gates and Burgoyne had their first interview (delineated on page 81) is about half way between the Fish Creek and Gates's headquarters. After visiting these localities, we returned to the village, and spent an hour upon the ground where the British army laid down their arms. This locality I have already noted, and will not detain the reader longer than to mention the fact that the plain whereon this event took place formed a part of the extensive meadows of General Schuyler, and to relate a characteristic adventure which occurred there.

While the British camp was on the north side of the Fish Creek, a number of the officers' horses were let loose in the meadows to feed. An expert swimmer among the Americans who swarmed upon the hills east of the Hudson, obtained permission to go across and capture one of the horses. He swam the river, seized and mounted a fine bay gelding, and in a few moments was recrossing the stream unharmed, amid a volley of bullets from a party of British soldiers. Shouts greeted him as he returned; and, when rested, he asked permission to go for another, telling the captain that he ought to have a horse to ride as well as a private. Again the adventurous soldier was among the herd, and, unscathed, returned with an exceedingly good match for the first, and presented it to his commander.(3)

Bidding our kind friend and guide adieu, we left Schuylerville toward evening, in a private carriage, for Fort Miller, six miles further up the Hudson. The same beautiful and diversified scenery, the same prevailing quiet that charmed us all the way from Waterford, still surrounded us; and the river and the narrow alluvial plain through which it flows, bounded on either side by high undulations or abrupt pyramidal hills, which cast lengthened shadows in the evening sun across the meadows, presented a beautiful picture of luxurious repose. We crossed the Hudson upon a long bridge built on strong abutments, two miles and a half above Schuylerville, at the place where Burgoyne and his army crossed on the 12th of September, 1777. The river is here quite broad and shallow, and broken by frequent rifts and rapids.

We arrived at Fort Miller village, on the east bank of the river, between five and six o'clock; and while awaiting supper, preparatory to an evening canal voyage to Fort Edward, nine miles above, I engaged a water-man to row me across to the western bank, to

1 The place where these barracks were located is just within

the northern suburb" of Schuylerville.

2 Davis, Green, Guiles, and Burden.

3 Neilson, 223

94

view the site of the old fort. He was a very obliging man, and well acquainted with the localities in the neighborhood, but was rather deficient in historical knowledge. His attempts to relate the events connected with the old fort and its vicinity were amusing; for Putnam's ambush on Lake Champlain, and the defeat of Pyles by Lee, in North Carolina, with a slight tincture of correct narrative, were blended together as pans of an event which, occurred at Fort Miller.

We crossed the Hudson just above the rapids. A dam for milling purposes spans the stream, causing a sluggish current and deeper water for more than two miles above. Here was the scene of one of Putnam's daring exploits. While a major in the English provincial army, nearly twenty years before the Revolution, he was lying in a bateau on the east side of the river, and was suddenly surprised by a party of Indians. He could not cross the river swiftly enough to escape the balls of their rifles, and there was no alternative but to go down the foaming rapids. In an instant his purpose was fixed, and, to the astonishment of the savages, he steered directly down the current, amid whirling eddies and over shelving rocks. In a few moments his vessel cleared the rush of waters, and was gliding upon the smooth current below, far out of reach of the weapons of the Indians. It was a feat they never dared attempt, and superstition convinced them that he was so favored by the Great Spirit that it would. be an affront to Manitou to attempt to kill him with powder and ball. Other Indians of the tribe, however, soon afterward gave practical evidence of their unbelief in such interposition.

There

is not a vestige of Fort Miller left, and maize, and potatoes, and pumpkin

vines were flourishing where the rival forces of Sir William Johnson and

the Baron Dieskau alternately paraded. At the foot of the hill, a few rods

below where the fort stood, is a part of the trench and bank of a redoubt,

and this is all that remains even of the outworks of the fortification.

There

is not a vestige of Fort Miller left, and maize, and potatoes, and pumpkin

vines were flourishing where the rival forces of Sir William Johnson and

the Baron Dieskau alternately paraded. At the foot of the hill, a few rods

below where the fort stood, is a part of the trench and bank of a redoubt,

and this is all that remains even of the outworks of the fortification.

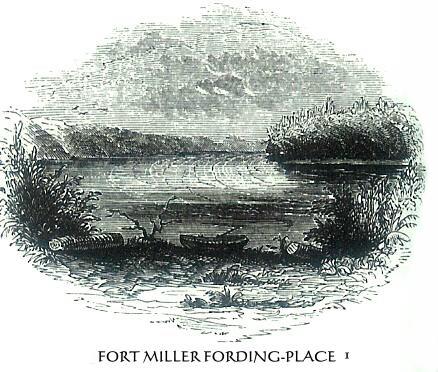

An eighth of a mile westward is Bloody Run, a stream which comes leaping in spark. ling cascades from the hills. and affords fine trout fishing. It derives its name from the fact that, while the English had possession of the fort in 1759, a party of soldiers from the garrison went out to fish at the place represented in the picture. The hills, now cultivated, were then covered with dense forests, and afforded the Indians excellent ambush. A troop of savages, lying near, sprang silently from their covert upon the fishers, and bore off nine reeking scalps before those who escaped could reach the fort and give the alarm.

This clear mountain stream enters the Hudson a little above Fort Miller,

where the river makes a  sudden

curve, and where, before the erection of the dam at the rapids, it was quite

shallow, and usually fordable. This was the crossing-place for the armies;

and there are still to be seen some of the logs and stones upon the shore

which formed a part of the old "King's Road" leading to the fording-place.

They are now sub-

sudden

curve, and where, before the erection of the dam at the rapids, it was quite

shallow, and usually fordable. This was the crossing-place for the armies;

and there are still to be seen some of the logs and stones upon the shore

which formed a part of the old "King's Road" leading to the fording-place.

They are now sub-

1 This view is taken from the site of the fort, looking northward. The fort was in the town of Northumberland. It was built of logs and earth, and was never a post of great importance.

95

merged, the river having been made deeper by the dam; but when the water

is limpid they can be plainly seen. It was twilight before we reached the

village on the eastern shore. We supped and repaired to the packet office,

where we waited until nine o'clock in the evening before the shrill notes

of a tin horn brayed out the annunciation of a packet near. Its deck was

covered with passengers, for the interesting ceremony of converting the

dining room into a dormitory, or swinging the hammocks or berths and selecting

their occupants, had commenced, and all were driven out, much to their own

comfort, but, strange to say, to the dissatisfaction of many who lazily

preferred a sweltering lounge in the cabin to the delights of fresh air

and the bright starlight. Having no interest in the scramble for beds, we

enjoyed the evening breeze and the excitement of the tiny tumult. My companion,

fearing the exhalations upon the night air, did indeed finally seek shelter

in one end of the cabin, but was driven, with two other young ladies, into

the captain's state-room, to allow the "hands" to have full play

in  making

the beds. Imprisoned against their will, the ladies made prompt restitution

to themselves by drawing the cork of a bottle of sarsaparilla and sipping

its contents, greatly to the consternation of a meek old dame, the mother

of one of the girls, who was sure it was bed-bug pizen, or some. thing a

pesky sight worse." We landed at Fort Edward at midnight, and took

lodgings at a small but tidily-kept tavern close by the canal.

making

the beds. Imprisoned against their will, the ladies made prompt restitution

to themselves by drawing the cork of a bottle of sarsaparilla and sipping

its contents, greatly to the consternation of a meek old dame, the mother

of one of the girls, who was sure it was bed-bug pizen, or some. thing a

pesky sight worse." We landed at Fort Edward at midnight, and took

lodgings at a small but tidily-kept tavern close by the canal.

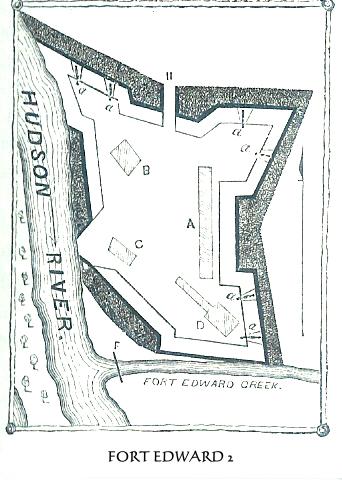

Fort Edward was a military post of considerable importance during the French and Indian wars and the Revolution.(1) The locality, previous to the erection of the fortress, was called thc first carrying-place, being the first and nearest point on the Hudson where the troops, stores, &c., were landed while passing to or from the south end of Lake Champlain, a distance of about twenty-five miles. The fort was built in 1755, when six thousand troops were collected there, under General Lyman, waiting the arrival of General Johnson, the commander-in-chief of an expedition against Ticonderoga and Crown Point. It was at first called Fort Lyman, in honor of the general who superintended its erection. It was built of logs and earth, sixteen feet high and twenty-two feet thick; and stood at the junction of Fort Edward Creek and the Hudson River. From the creek, around the fort to the river, was a deep fosse or ditch, designated in the engraving by the dark dotted part outside of the black lines.

1 I refer particularly to the war between England and France,

commonly called, in Europe, the Seven Years' War. It was declared on  the

9th of June, 1756, and ended with the treaty at Paris, concluded and signed

February 10th, 1763. It extended to the colonies of the two nations in America,

and was carried on with much vigor here until the victory of Wolfe at Quebec,

in 1759, and the entire subjugation of Canada by the English. The French

managed to enlist a large proportion of the Indian tribes in their favor,

who were allied with them against the Britons. It is for that reason that

the section of the Seven Years' War in America was called by the colonists

the "French and Indian War." I would here mention incidentally

that that war cost Great Britain five hundred and sixty millions of dollars,

and laid one of the largest foundation stones of that national debt under

which she now groans. It was twenty millions in the reign of William and

Mary, in 1697, and was then thought to be enormous; in 1840 it was about

four thousand millions of dollars!

the

9th of June, 1756, and ended with the treaty at Paris, concluded and signed

February 10th, 1763. It extended to the colonies of the two nations in America,

and was carried on with much vigor here until the victory of Wolfe at Quebec,

in 1759, and the entire subjugation of Canada by the English. The French

managed to enlist a large proportion of the Indian tribes in their favor,

who were allied with them against the Britons. It is for that reason that

the section of the Seven Years' War in America was called by the colonists

the "French and Indian War." I would here mention incidentally

that that war cost Great Britain five hundred and sixty millions of dollars,

and laid one of the largest foundation stones of that national debt under

which she now groans. It was twenty millions in the reign of William and

Mary, in 1697, and was then thought to be enormous; in 1840 it was about

four thousand millions of dollars!

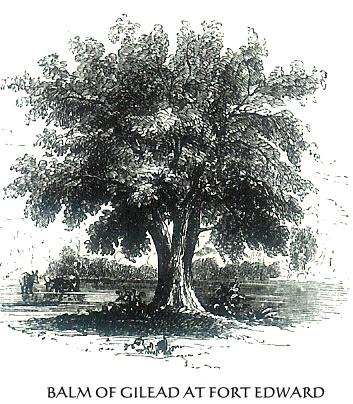

2 EXPLANATION: a a a a a a, six cannons; A, the barracks; B, the store-house;

C, the hospital; D, the magazine; E, a flanker; F, a bridge across Fort

Edward Creek; and G, a balm of Gilead tree which then overshadowed the massive.

water-gate. That tree is still standing, a majestic relic of the past, amid

the surrounding changes in nature and art. It is directly upon the high

bank of the Hudson, and its branches, heavily foliated when I was there,

spread very high and wide. At the union below its three trunks it measures

more than twenty feet in circumference.